This blog post assumes that the reader is aware of text generation methods using different variants of beam search, as explained within the blog post: “The best way to generate text: using different decoding methods for language generation with Transformers”

Unlike peculiar beam search, constrained beam search allows us to exert control over the output of text generation. This is beneficial because we sometimes know exactly what we wish contained in the output. For instance, in a Neural Machine Translation task, we’d know which words should be included in the ultimate translation with a dictionary lookup. Sometimes, generation outputs which are almost equally possible to a language model may not be equally desirable for the end-user attributable to the actual context. Each of those situations may very well be solved by allowing the users to inform the model which words should be included in the long run output.

Why It’s Difficult

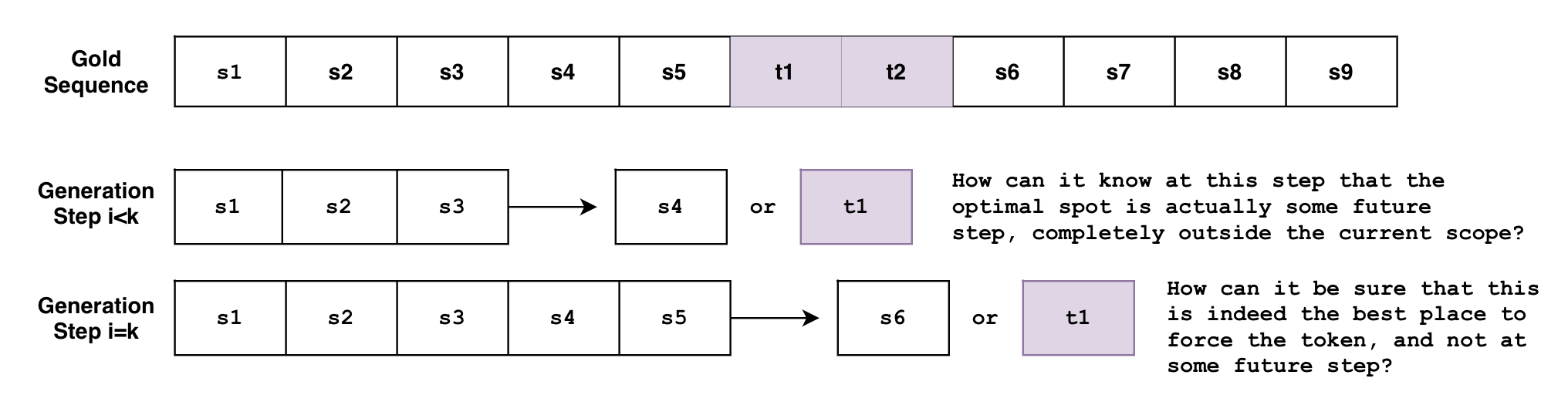

Nonetheless, this is definitely a really non-trivial problem. It’s because the duty requires us to force the generation of certain subsequences somewhere in the ultimate output, at some point throughout the generation.

For instance that we’re need to generate a sentence S that has to incorporate the phrase with tokens so as. Let’s define the expected sentence as:

The issue is that beam search generates the sequence token-by-token. Though not entirely accurate, one can consider beam search because the function , where it looks on the currently generated sequence of tokens from to then predicts the following token at . But how can this function know, at an arbitrary step , that the tokens should be generated at some future step ? Or when it’s on the step , how can it know obviously that that is one of the best spot to force the tokens, as a substitute of some future step ?

And what if you’ve got multiple constraints with various requirements? What if you wish to force the phrase and also the phrase ? What should you want the model to make a choice from the 2 phrases? What if we wish to force the phrase and force only one phrase among the many list of phrases ?

The above examples are literally very reasonable use-cases, as it should be shown below, and the brand new constrained beam search feature allows for all of them!

This post will quickly go over what the brand new constrained beam search feature can do for you after which go into deeper details about how it really works under the hood.

Example 1: Forcing a Word

For instance we’re attempting to translate "How old are you?" to German.

"Wie alt bist du?" is what you’d say in a casual setting, and "Wie alt sind Sie?" is what

you’d say in a proper setting.

And depending on the context, we’d want one form of ritual over the opposite, but how can we tell the model that?

Traditional Beam Search

Here’s how we’d do text translation within the traditional beam search setting.

!pip install -q git+https://github.com/huggingface/transformers.git

from transformers import AutoTokenizer, AutoModelForSeq2SeqLM

tokenizer = AutoTokenizer.from_pretrained("t5-base")

model = AutoModelForSeq2SeqLM.from_pretrained("t5-base")

encoder_input_str = "translate English to German: How old are you?"

input_ids = tokenizer(encoder_input_str, return_tensors="pt").input_ids

outputs = model.generate(

input_ids,

num_beams=10,

num_return_sequences=1,

no_repeat_ngram_size=1,

remove_invalid_values=True,

)

print("Output:n" + 100 * '-')

print(tokenizer.decode(outputs[0], skip_special_tokens=True))

Output:

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Wie alt bist du?

With Constrained Beam Search

But what if we knew that we wanted a proper output as a substitute of the informal one? What if we knew from prior knowledge what the generation must include, and we could inject it into the generation?

The next is what is feasible now with the force_words_ids keyword argument to model.generate():

tokenizer = AutoTokenizer.from_pretrained("t5-base")

model = AutoModelForSeq2SeqLM.from_pretrained("t5-base")

encoder_input_str = "translate English to German: How old are you?"

force_words = ["Sie"]

input_ids = tokenizer(encoder_input_str, return_tensors="pt").input_ids

force_words_ids = tokenizer(force_words, add_special_tokens=False).input_ids

outputs = model.generate(

input_ids,

force_words_ids=force_words_ids,

num_beams=5,

num_return_sequences=1,

no_repeat_ngram_size=1,

remove_invalid_values=True,

)

print("Output:n" + 100 * '-')

print(tokenizer.decode(outputs[0], skip_special_tokens=True))

Output:

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Wie alt sind Sie?

As you may see, we were in a position to guide the generation with prior knowledge about our desired output. Previously we’d’ve needed to generate a bunch of possible outputs, then filter those that fit our requirement. Now we are able to try this on the generation stage.

Example 2: Disjunctive Constraints

We mentioned above a use-case where we all know which words we wish to be included in the ultimate output. An example of this is likely to be using a dictionary lookup during neural machine translation.

But what if we do not know which word forms to make use of, where we might want outputs like ["raining", "rained", "rains", ...] to be equally possible? In a more general sense, there are at all times cases after we don’t desire the exact word verbatim, letter by letter, and is likely to be open to other related possibilities too.

Constraints that allow for this behavior are Disjunctive Constraints, which permit the user to input a listing of words, whose purpose is to guide the generation such that the ultimate output must contain just at the very least one among the many list of words.

Here’s an example that uses a mixture of the above two varieties of constraints:

from transformers import GPT2LMHeadModel, GPT2Tokenizer

model = GPT2LMHeadModel.from_pretrained("gpt2")

tokenizer = GPT2Tokenizer.from_pretrained("gpt2")

force_word = "scared"

force_flexible = ["scream", "screams", "screaming", "screamed"]

force_words_ids = [

tokenizer([force_word], add_prefix_space=True, add_special_tokens=False).input_ids,

tokenizer(force_flexible, add_prefix_space=True, add_special_tokens=False).input_ids,

]

starting_text = ["The soldiers", "The child"]

input_ids = tokenizer(starting_text, return_tensors="pt").input_ids

outputs = model.generate(

input_ids,

force_words_ids=force_words_ids,

num_beams=10,

num_return_sequences=1,

no_repeat_ngram_size=1,

remove_invalid_values=True,

)

print("Output:n" + 100 * '-')

print(tokenizer.decode(outputs[0], skip_special_tokens=True))

print(tokenizer.decode(outputs[1], skip_special_tokens=True))

Setting `pad_token_id` to `eos_token_id`:50256 for open-end generation.

Output:

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The soldiers, who were all scared and screaming at one another as they tried to get out of the

The kid was taken to a neighborhood hospital where she screamed and scared for her life, police said.

As you may see, the primary output used "screaming", the second output used "screamed", and each used "scared" verbatim. The list to select from ["screaming", "screamed", ...] doesn’t need to be word forms; this will satisfy any use-case where we’d like only one from a listing of words.

Traditional Beam search

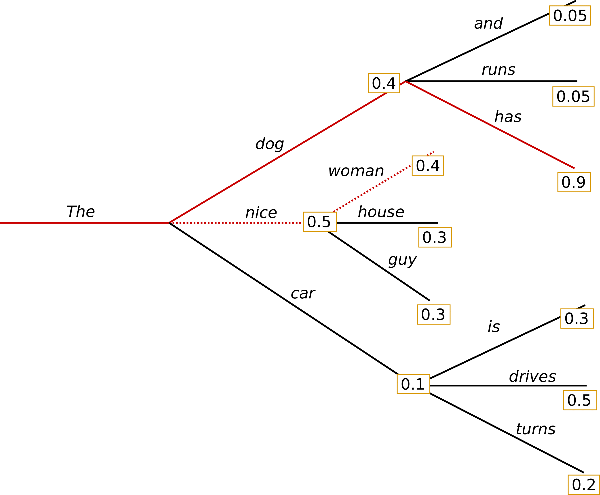

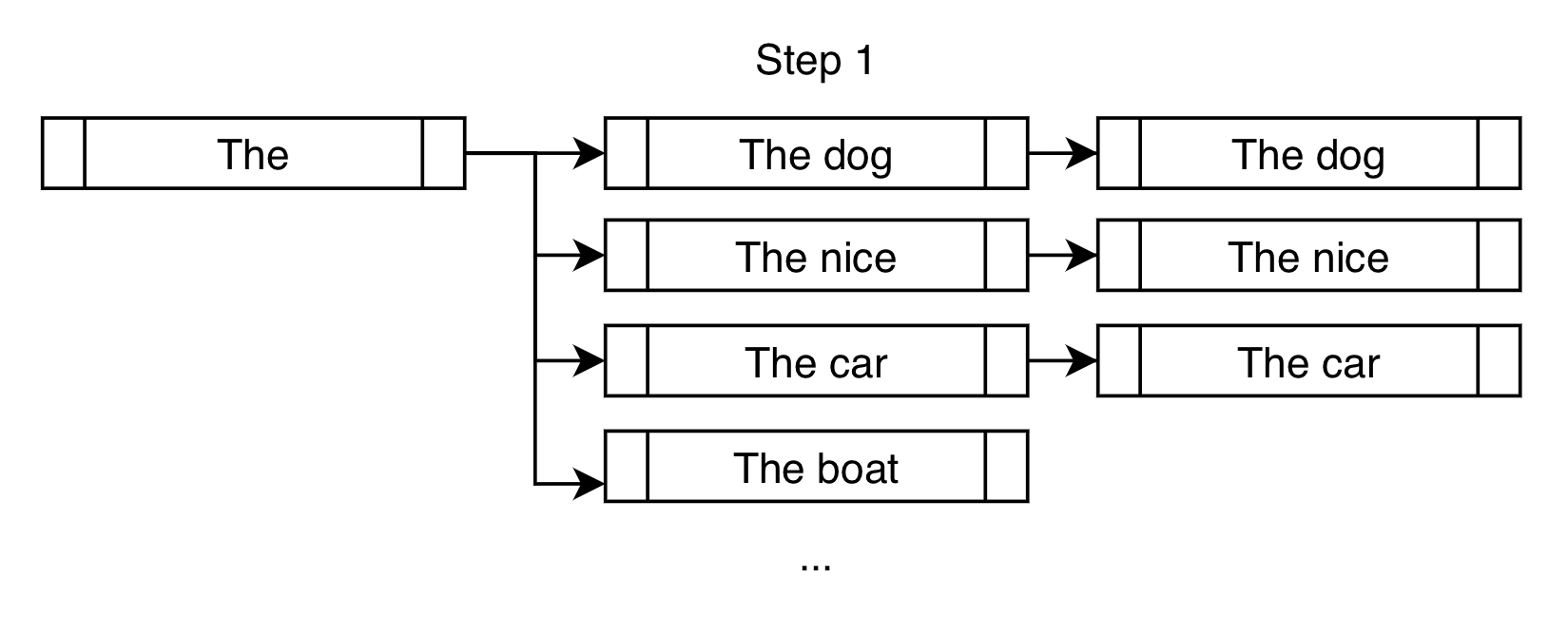

The next is an example of traditional beam search, taken from a previous blog post:

Unlike greedy search, beam search works by keeping an extended list of hypotheses. Within the above picture, we now have displayed three next possible tokens at each possible step within the generation.

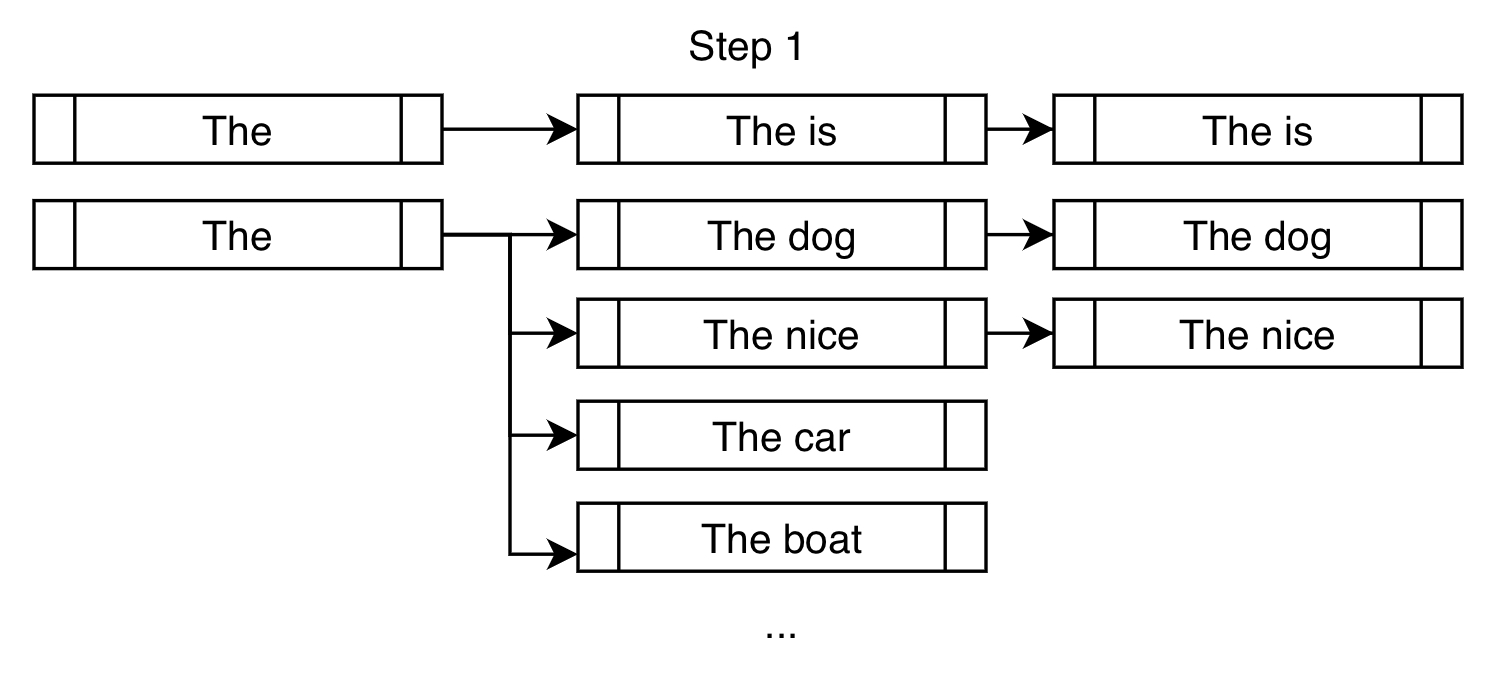

Here’s one other approach to have a look at step one of the beam seek for the above example, within the case of num_beams=3:

As an alternative of only selecting "The dog" like what a greedy search would do, a beam search would allow further consideration of "The great" and "The automobile".

In the following step, we consider the following possible tokens for every of the three branches we created within the previous step.

Though we find yourself considering significantly greater than num_beams outputs, we reduce them all the way down to num_beams at the tip of the step. We will not just keep branching out, then the variety of beams we might need to keep track of could be for steps, which becomes very large in a short time ( beams after steps is beams!).

For the remainder of the generation, we repeat the above step until the ending criteria has been met, like generating the max_length, for instance. Branch out, rank, reduce, and repeat.

Constrained Beam Search

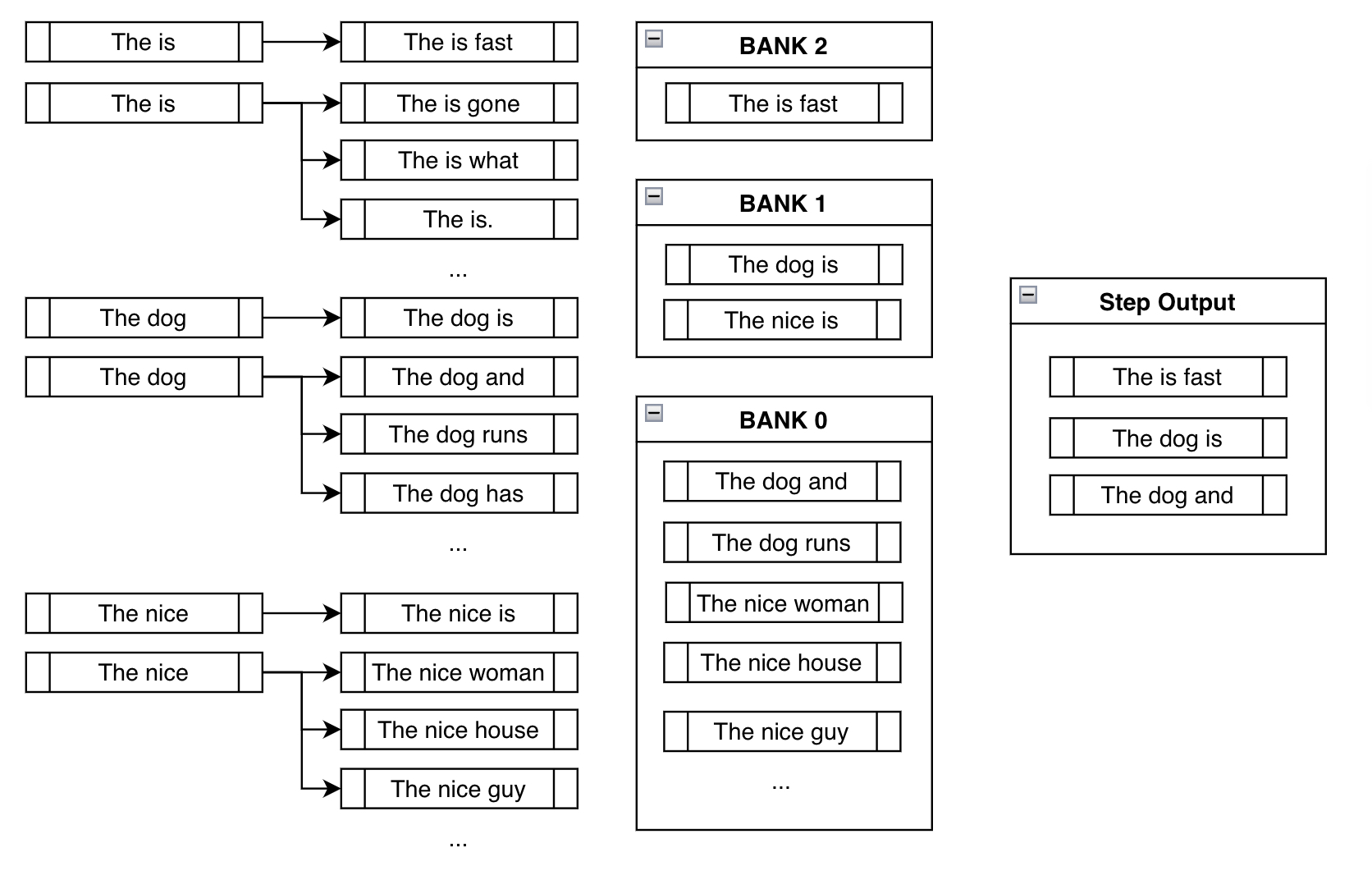

Constrained beam search attempts to meet the constraints by injecting the specified tokens at every step of the generation.

For instance that we’re attempting to force the phrase "is fast" within the generated output.

In the standard beam search setting, we discover the highest k most probable next tokens at each branch and append them for consideration. Within the constrained setting, we do the identical but in addition append the tokens that may take us closer to fulfilling our constraints. Here’s an indication:

On top of the same old high-probability next tokens like "dog" and "nice", we force the token "is" with the intention to get us closer to fulfilling our constraint of "is fast".

For the following step, the branched-out candidates below are mostly the identical as that of traditional beam search. But just like the above example, constrained beam search adds onto the present candidates by forcing the constraints at each latest branch:

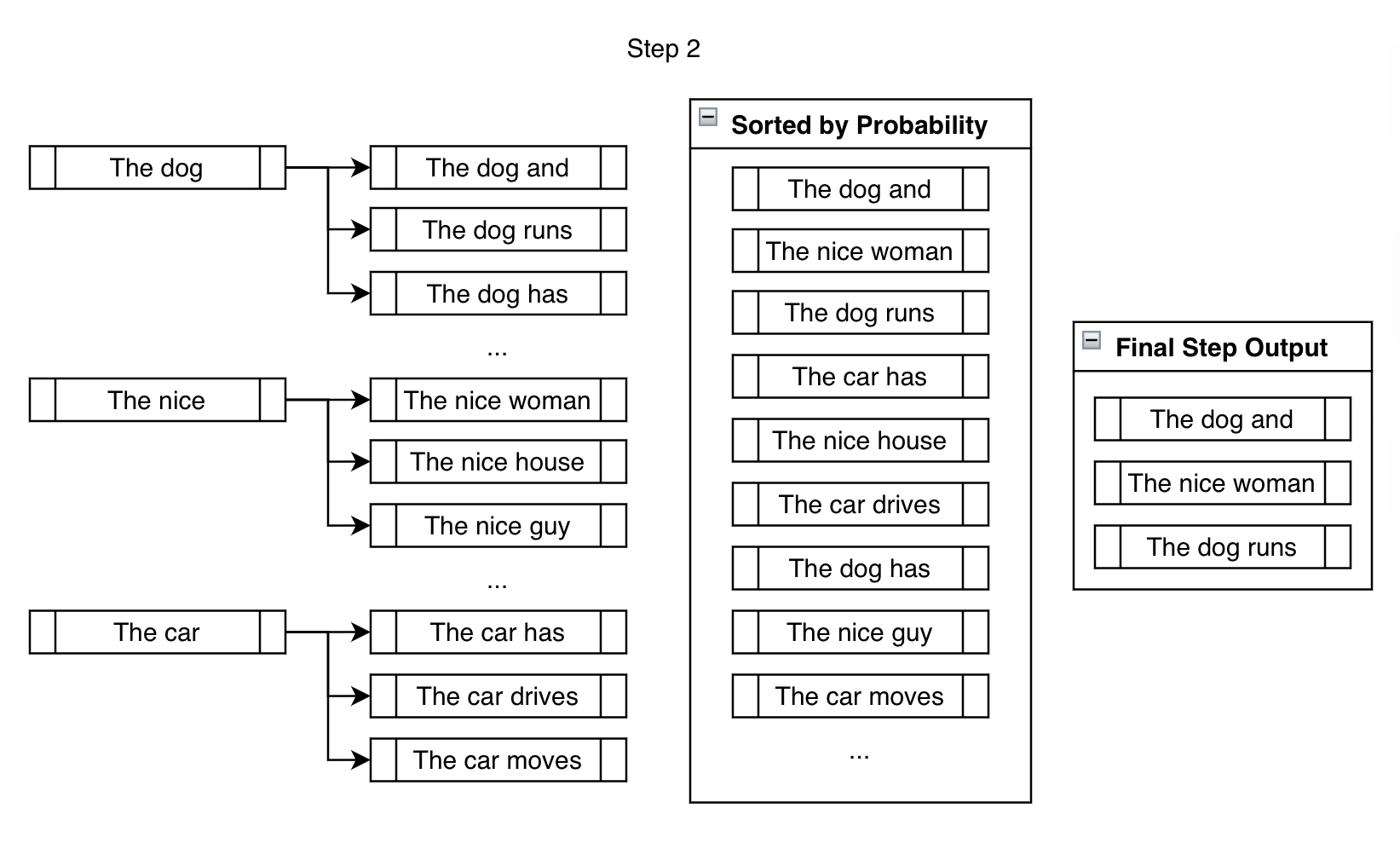

Banks

Before we talk in regards to the next step, we’d like to think in regards to the resulting undesirable behavior we are able to see within the above step.

The issue with naively just forcing the specified phrase "is fast" within the output is that, more often than not, you’d find yourself with nonsensical outputs like "The is fast" above. This is definitely what makes this a nontrivial problem to unravel. A deeper discussion in regards to the complexities of solving this problem could be present in the original feature request issue that was raised in huggingface/transformers.

Banks solve this problem by making a balance between fulfilling the constraints and creating sensible output.

Bank refers back to the list of beams which have made steps progress in fulfilling the constraints. After sorting all of the possible beams into their respective banks, we do a round-robin selection. With the above example, we might select essentially the most probable output from Bank 2, then most probable from Bank 1, one from Bank 0, the second most probable from Bank 2, the second most probable from Bank 1, and so forth. Since we’re using num_beams=3, we just do the above process 3 times to find yourself with ["The is fast", "The dog is", "The dog and"].

This fashion, though we’re forcing the model to think about the branch where we have manually appended the specified token, we still keep track of other high-probable sequences that probably make more sense. Although "The is fast" fulfills our constraint completely, it isn’t a really sensible phrase. Luckily, we now have "The dog is" and "The dog and" to work with in future steps, which hopefully will result in more sensible outputs afterward.

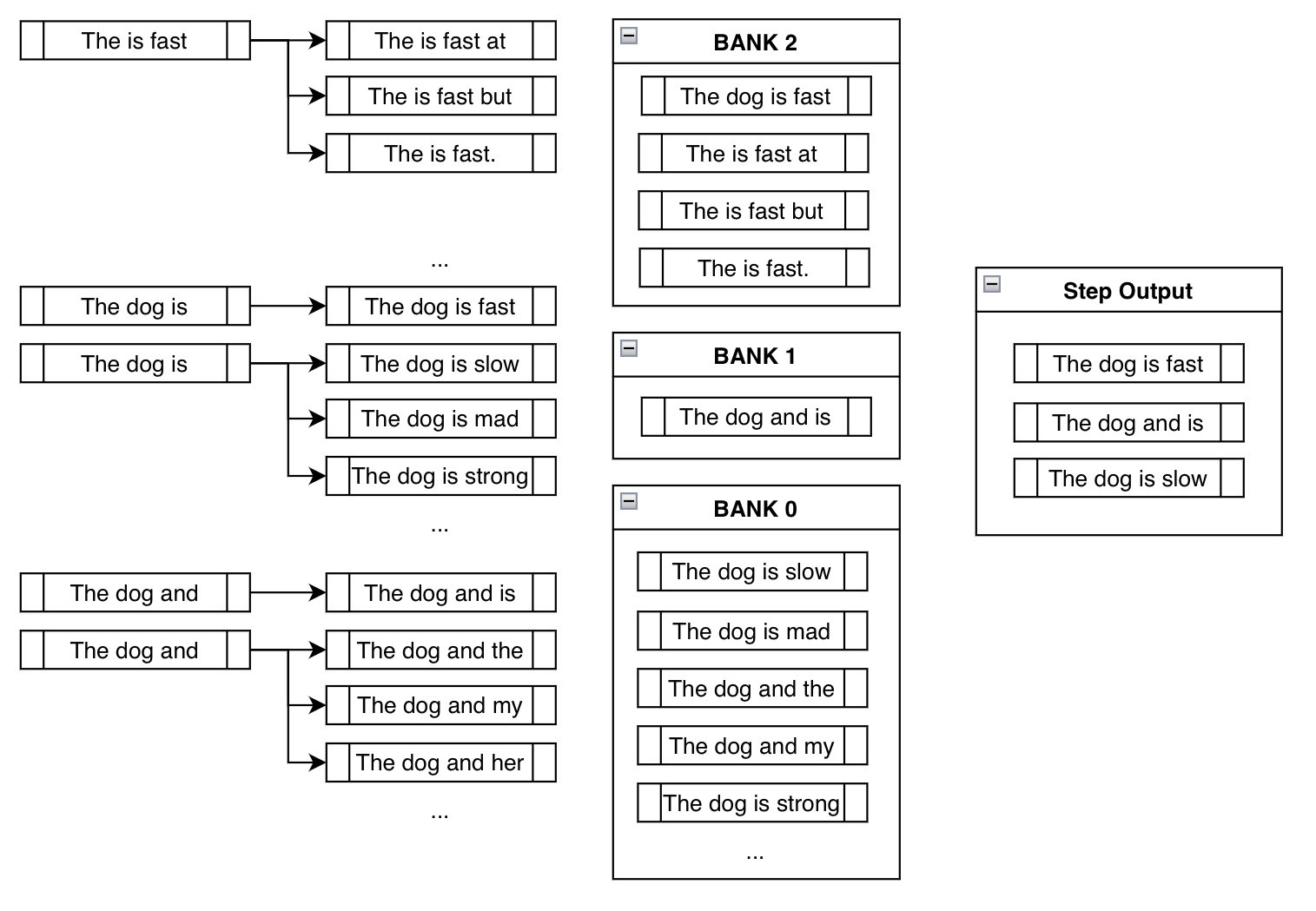

This behavior is demonstrated within the third step of the above example:

Notice how "The is fast" doesn’t require any manual appending of constraint tokens because it’s already fulfilled (i.e., already incorporates the phrase "is fast"). Also, notice how beams like "The dog is slow" or "The dog is mad" are literally in Bank 0, since, even though it includes the token "is", it must restart from the start to generate "is fast". By appending something like "slow" after "is", it has effectively reset its progress.

And eventually notice how we ended up at a smart output that incorporates our constraint phrase: "The dog is fast"!

We were nervous initially because blindly appending the specified tokens led to nonsensical phrases like "The is fast". Nonetheless, using round-robin selection from banks, we implicitly ended up eliminating nonsensical outputs in preference for the more sensible outputs.

More About Constraint Classes and Custom Constraints

The major takeaway from the reason could be summarized as the next. At every step, we keep pestering the model to think about the tokens that fulfill our constraints, all of the while keeping track of beams that do not, until we find yourself with reasonably high probability sequences that contain our desired phrases.

So a principled approach to design this implementation was to represent each constraint as a Constraint object, whose purpose was to maintain track of its progress and tell the beam search which tokens to generate next. Although we now have provided the keyword argument force_words_ids for model.generate(), the next is what actually happens within the back-end:

from transformers import AutoTokenizer, AutoModelForSeq2SeqLM, PhrasalConstraint

tokenizer = AutoTokenizer.from_pretrained("t5-base")

model = AutoModelForSeq2SeqLM.from_pretrained("t5-base")

encoder_input_str = "translate English to German: How old are you?"

constraints = [

PhrasalConstraint(

tokenizer("Sie", add_special_tokens=False).input_ids

)

]

input_ids = tokenizer(encoder_input_str, return_tensors="pt").input_ids

outputs = model.generate(

input_ids,

constraints=constraints,

num_beams=10,

num_return_sequences=1,

no_repeat_ngram_size=1,

remove_invalid_values=True,

)

print("Output:n" + 100 * '-')

print(tokenizer.decode(outputs[0], skip_special_tokens=True))

Output:

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Wie alt sind Sie?

You’ll be able to define one yourself and input it into the constraints keyword argument to design your unique constraints. You simply need to create a sub-class of the Constraint abstract interface class and follow its requirements. You will discover more information within the definition of Constraint found here.

Some unique ideas (not yet implemented; perhaps you may give it a try!) include constraints like OrderedConstraints, TemplateConstraints that could be added further down the road. Currently, the generation is fulfilled by including the sequences, wherever within the output. For instance, a previous example had one sequence with scared -> screaming and the opposite with screamed -> scared. OrderedConstraints could allow the user to specify the order by which these constraints are fulfilled.

TemplateConstraints could allow for a more area of interest use of the feature, where the target could be something like:

starting_text = "The lady"

template = ["the", "", "School of", "", "in"]

possible_outputs == [

"The woman attended the Ross School of Business in Michigan.",

"The woman was the administrator for the Harvard School of Business in MA."

]

or:

starting_text = "The lady"

template = ["the", "", "", "University", "", "in"]

possible_outputs == [

"The woman attended the Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh.",

]

impossible_outputs == [

"The woman attended the Harvard University in MA."

]

or if the user doesn’t care in regards to the variety of tokens that may go in between two words, then one can just use OrderedConstraint.

Conclusion

Constrained beam search gives us a versatile means to inject external knowledge and requirements into text generation. Previously, there was no easy approach to tell the model to 1. include a listing of sequences where 2. a few of that are optional and a few will not be, such that 3. they’re generated somewhere within the sequence at respective reasonable positions. Now, we are able to have full control over our generation with a mixture of various subclasses of Constraint objects!

This latest feature relies mainly on the next papers:

Just like the ones above, many latest research papers are exploring ways of using external knowledge (e.g., KGs, KBs) to guide the outputs of enormous deep learning models. Hopefully, this constrained beam search feature becomes one other effective approach to achieve this purpose.

Due to everybody that gave guidance for this feature contribution: Patrick von Platen for being involved from the initial issue to the final PR, and Narsil Patry, for providing detailed feedback on the code.

Thumbnail of this post uses an icon with the attribution: Shorthand icons created by Freepik – Flaticon