A number of months ago we introduced the Time Series Transformer, which is the vanilla Transformer (Vaswani et al., 2017) applied to forecasting, and showed an example for the univariate probabilistic forecasting task (i.e. predicting every time series’ 1-d distribution individually). On this post we introduce the Informer model (Zhou, Haoyi, et al., 2021), AAAI21 best paper which is now available in 🤗 Transformers. We’ll show the right way to use the Informer model for the multivariate probabilistic forecasting task, i.e., predicting the distribution of a future vector of time-series goal values. Note that this can even work for the vanilla Time Series Transformer model.

Multivariate Probabilistic Time Series Forecasting

So far as the modeling aspect of probabilistic forecasting is worried, the Transformer/Informer would require no change when coping with multivariate time series. In each the univariate and multivariate setting, the model will receive a sequence of vectors and thus the one change is on the output or emission side.

Modeling the complete joint conditional distribution of high dimensional data can get computationally expensive and thus methods resort to some approximation of the distribution, the best being to model the information as an independent distribution from the identical family, or some low-rank approximation to the complete covariance, etc. Here we’ll just resort to the independent (or diagonal) emissions that are supported for the families of distributions we have now implemented here.

Informer – Under The Hood

Based on the vanilla Transformer (Vaswani et al., 2017), Informer employs two major improvements. To know these improvements, let’s recall the drawbacks of the vanilla Transformer:

- Quadratic computation of canonical self-attention: The vanilla Transformer has a computational complexity of where is the time series length and is the dimension of the hidden states. For long sequence time-series forecasting (also generally known as the LSTF problem), this is likely to be really computationally expensive. To unravel this problem, Informer employs a brand new self-attention mechanism called ProbSparse attention, which has time and space complexity.

- Memory bottleneck when stacking layers: When stacking encoder/decoder layers, the vanilla Transformer has a memory usage of , which limits the model’s capability for long sequences. Informer uses a Distilling operation, for reducing the input size between layers into its half slice. By doing so, it reduces the entire memory usage to be .

As you’ll be able to see, the motivation for the Informer model is comparable to Longformer (Beltagy et el., 2020), Sparse Transformer (Child et al., 2019) and other NLP papers for reducing the quadratic complexity of the self-attention mechanism when the input sequence is long. Now, let’s dive into ProbSparse attention and the Distilling operation with code examples.

ProbSparse Attention

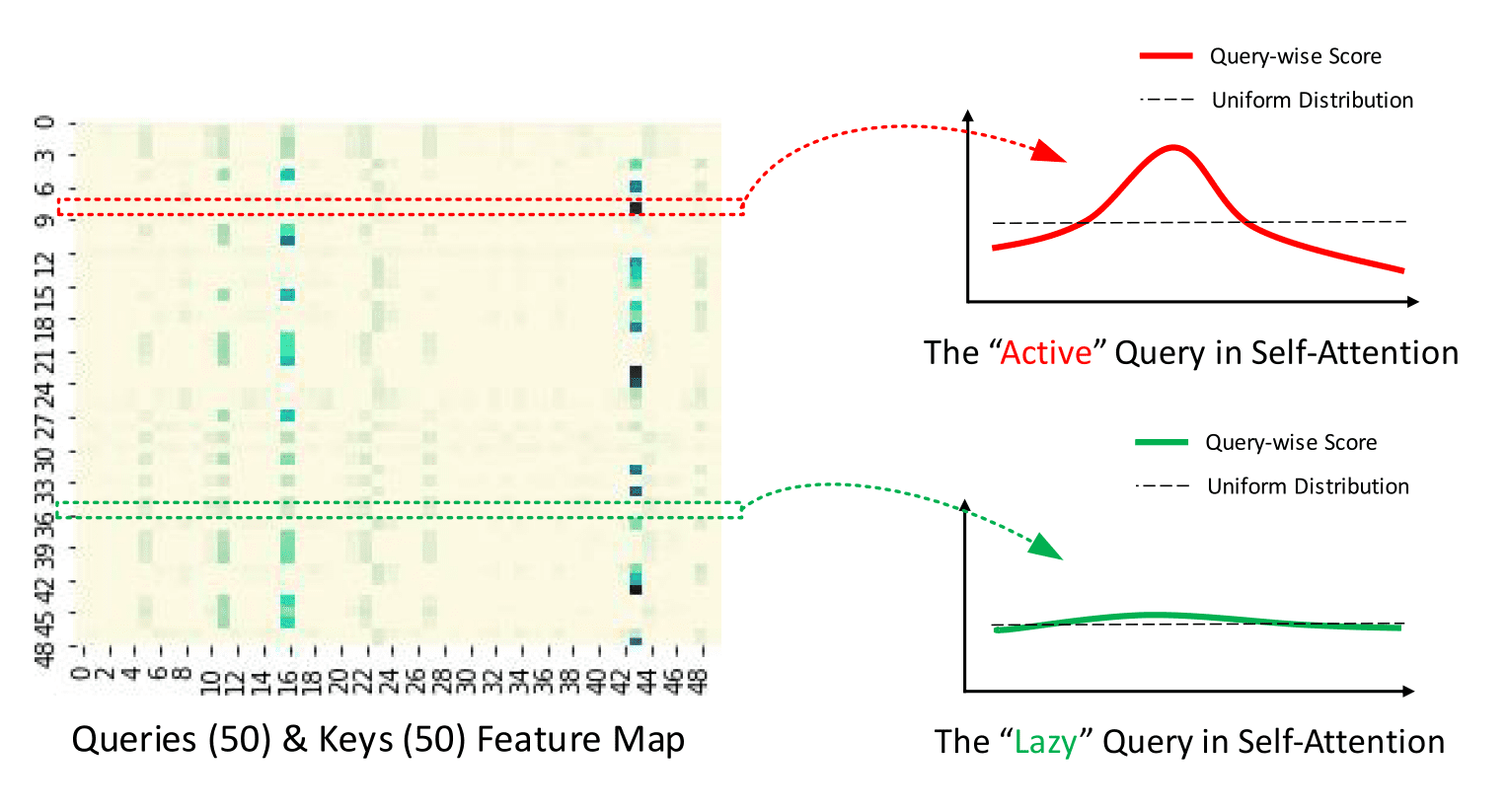

The foremost idea of ProbSparse is that the canonical self-attention scores form a long-tail distribution, where the “energetic” queries lie within the “head” scores and “lazy” queries lie within the “tail” area. By “energetic” query we mean a question such that the dot-product contributes to the foremost attention, whereas a “lazy” query forms a dot-product which generates trivial attention. Here, and are the -th rows in and attention matrices respectively.

Given the concept of “energetic” and “lazy” queries, the ProbSparse attention selects the “energetic” queries, and creates a reduced query matrix which is used to calculate the eye weights in . Let’s have a look at this more intimately with a code example.

Recall the canonical self-attention formula:

Where , and . Note that in practice, the input length of queries and keys are typically equivalent within the self-attention computation, i.e. where is the time series length. Due to this fact, the multiplication takes computational complexity. In ProbSparse attention, our goal is to create a brand new matrix and define:

where the matrix only selects the Top “energetic” queries. Here, and called the sampling factor hyperparameter for the ProbSparse attention. Since selects only the Top queries, its size is , so the multiplication takes only .

This is sweet! But how can we select the “energetic” queries to create ? Let’s define the Query Sparsity Measurement.

Query Sparsity Measurement

Query Sparsity Measurement is used for choosing the “energetic” queries in to create . In theory, the dominant pairs encourage the “energetic” ‘s probability distribution away from the uniform distribution as might be seen within the figure below. Hence, the KL divergence between the actual queries distribution and the uniform distribution is used to define the sparsity measurement.

|

|---|

| The illustration of ProbSparse Attention from official repository |

In practice, the measurement is defined as:

The essential thing to know here is when is larger, the query must be in and vice versa.

But how can we calculate the term in non-quadratic time? Recall that almost all of the dot-product generate either way the trivial attention (i.e. long-tail distribution property), so it is sufficient to randomly sample a subset of keys from , which might be called K_sample within the code.

Now, we’re able to see the code of probsparse_attention:

from torch import nn

import math

def probsparse_attention(query_states, key_states, value_states, sampling_factor=5):

"""

Compute the probsparse self-attention.

Input shape: Batch x Time x Channel

Note the extra `sampling_factor` input.

"""

L_K = key_states.size(1)

L_Q = query_states.size(1)

log_L_K = np.ceil(np.log1p(L_K)).astype("int").item()

log_L_Q = np.ceil(np.log1p(L_Q)).astype("int").item()

U_part = min(sampling_factor * L_Q * log_L_K, L_K)

index_sample = torch.randint(0, L_K, (U_part,))

K_sample = key_states[:, index_sample, :]

Q_K_sample = torch.bmm(query_states, K_sample.transpose(1, 2))

M = Q_K_sample.max(dim=-1)[0] - torch.div(Q_K_sample.sum(dim=-1), L_K)

u = min(sampling_factor * log_L_Q, L_Q)

M_top = M.topk(u, sorted=False)[1]

dim_for_slice = torch.arange(query_states.size(0)).unsqueeze(-1)

Q_reduce = query_states[dim_for_slice, M_top]

d_k = query_states.size(-1)

attn_scores = torch.bmm(Q_reduce, key_states.transpose(-2, -1))

attn_scores = attn_scores / math.sqrt(d_k)

attn_probs = nn.functional.softmax(attn_scores, dim=-1)

attn_output = torch.bmm(attn_probs, value_states)

return attn_output, attn_scores

Note that within the implementation, contain within the calculation, for stability issues (see this disccusion for more information).

We did it! Please remember that this is just a partial implementation of the probsparse_attention, and the complete implementation might be present in 🤗 Transformers.

Distilling

Due to the ProbSparse self-attention, the encoder’s feature map has some redundancy that might be removed. Due to this fact,

the distilling operation is used to cut back the input size between encoder layers into its half slice, thus in theory removing this redundancy. In practice, Informer’s “distilling” operation just adds 1D convolution layers with max pooling between each of the encoder layers. Let be the output of the -th encoder layer, the distilling operation is then defined as:

Let’s have a look at this in code:

from torch import nn

def informer_encoder_forward(x_input, num_encoder_layers=3, distil=True):

if distil:

conv_layers = nn.ModuleList([ConvLayer() for _ in range(num_encoder_layers - 1)])

conv_layers.append(None)

else:

conv_layers = [None] * num_encoder_layers

for encoder_layer, conv_layer in zip(encoder_layers, conv_layers):

output = encoder_layer(x_input)

if conv_layer is not None:

output = conv_layer(loutput)

return output

By reducing the input of every layer by two, we get a memory usage of as an alternative of where is the variety of encoder/decoder layers. That is what we wanted!

The Informer model in now available within the 🤗 Transformers library, and easily called InformerModel. Within the sections below, we’ll show the right way to train this model on a custom multivariate time-series dataset.

Set-up Environment

First, let’s install the obligatory libraries: 🤗 Transformers, 🤗 Datasets, 🤗 Evaluate, 🤗 Speed up and GluonTS.

As we’ll show, GluonTS might be used for transforming the information to create features in addition to for creating appropriate training, validation and test batches.

!pip install -q transformers datasets evaluate speed up gluonts ujson

Load Dataset

On this blog post, we’ll use the traffic_hourly dataset, which is out there on the Hugging Face Hub. This dataset accommodates the San Francisco Traffic dataset utilized by Lai et al. (2017). It accommodates 862 hourly time series showing the road occupancy rates within the range on the San Francisco Bay area freeways from 2015 to 2016.

This dataset is an element of the Monash Time Series Forecasting repository, a group of time series datasets from various domains. It may be viewed because the GLUE benchmark of time series forecasting.

from datasets import load_dataset

dataset = load_dataset("monash_tsf", "traffic_hourly")

As might be seen, the dataset accommodates 3 splits: train, validation and test.

dataset

>>> DatasetDict({

train: Dataset({

features: ['start', 'target', 'feat_static_cat', 'feat_dynamic_real', 'item_id'],

num_rows: 862

})

test: Dataset({

features: ['start', 'target', 'feat_static_cat', 'feat_dynamic_real', 'item_id'],

num_rows: 862

})

validation: Dataset({

features: ['start', 'target', 'feat_static_cat', 'feat_dynamic_real', 'item_id'],

num_rows: 862

})

})

Each example accommodates just a few keys, of which start and goal are crucial ones. Allow us to have a have a look at the primary time series within the dataset:

train_example = dataset["train"][0]

train_example.keys()

>>> dict_keys(['start', 'target', 'feat_static_cat', 'feat_dynamic_real', 'item_id'])

The start simply indicates the beginning of the time series (as a datetime), and the goal accommodates the actual values of the time series.

The start might be useful so as to add time related features to the time series values, as extra input to the model (comparable to “month of yr”). Since we all know the frequency of the information is hourly, we all know as an illustration that the second value has the timestamp 2015-01-01 01:00:01, 2015-01-01 02:00:01, etc.

print(train_example["start"])

print(len(train_example["target"]))

>>> 2015-01-01 00:00:01

17448

The validation set accommodates the identical data because the training set, only for a prediction_length longer period of time. This enables us to validate the model’s predictions against the bottom truth.

The test set is again one prediction_length longer data in comparison with the validation set (or some multiple of prediction_length longer data in comparison with the training set for testing on multiple rolling windows).

validation_example = dataset["validation"][0]

validation_example.keys()

>>> dict_keys(['start', 'target', 'feat_static_cat', 'feat_dynamic_real', 'item_id'])

The initial values are the exact same because the corresponding training example. Nevertheless, this instance has prediction_length=48 (48 hours, or 2 days) additional values in comparison with the training example. Allow us to confirm it.

freq = "1H"

prediction_length = 48

assert len(train_example["target"]) + prediction_length == len(

dataset["validation"][0]["target"]

)

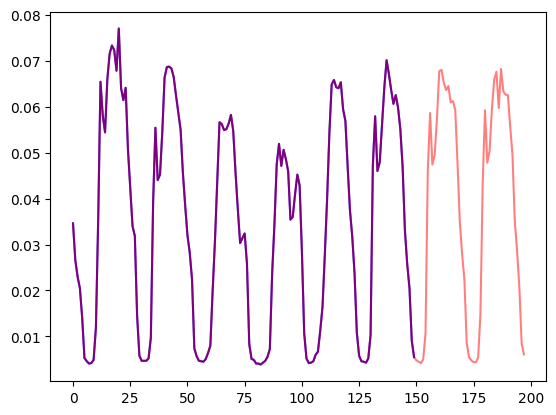

Let’s visualize this:

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

num_of_samples = 150

figure, axes = plt.subplots()

axes.plot(train_example["target"][-num_of_samples:], color="blue")

axes.plot(

validation_example["target"][-num_of_samples - prediction_length :],

color="red",

alpha=0.5,

)

plt.show()

Let’s split up the information:

train_dataset = dataset["train"]

test_dataset = dataset["test"]

Update start to pd.Period

The very first thing we’ll do is convert the start feature of every time series to a pandas Period index using the information’s freq:

from functools import lru_cache

import pandas as pd

import numpy as np

@lru_cache(10_000)

def convert_to_pandas_period(date, freq):

return pd.Period(date, freq)

def transform_start_field(batch, freq):

batch["start"] = [convert_to_pandas_period(date, freq) for date in batch["start"]]

return batch

We now use datasets‘ set_transform functionality to do that on-the-fly in place:

from functools import partial

train_dataset.set_transform(partial(transform_start_field, freq=freq))

test_dataset.set_transform(partial(transform_start_field, freq=freq))

Now, let’s convert the dataset right into a multivariate time series using the MultivariateGrouper from GluonTS. This grouper will convert the person 1-dimensional time series right into a single 2D matrix.

from gluonts.dataset.multivariate_grouper import MultivariateGrouper

num_of_variates = len(train_dataset)

train_grouper = MultivariateGrouper(max_target_dim=num_of_variates)

test_grouper = MultivariateGrouper(

max_target_dim=num_of_variates,

num_test_dates=len(test_dataset) // num_of_variates,

)

multi_variate_train_dataset = train_grouper(train_dataset)

multi_variate_test_dataset = test_grouper(test_dataset)

Note that the goal is now 2-dimensional, where the primary dimension is the variety of variates (variety of time series) and the second is the time series values (time dimension):

multi_variate_train_example = multi_variate_train_dataset[0]

print("multi_variate_train_example["target"].shape =", multi_variate_train_example["target"].shape)

>>> multi_variate_train_example["target"].shape = (862, 17448)

Define the Model

Next, let’s instantiate a model. The model might be trained from scratch, hence we can’t use the from_pretrained method here, but quite randomly initialize the model from a config.

We specify a few additional parameters to the model:

prediction_length(in our case,48hours): that is the horizon that the decoder of the Informer will learn to predict for;context_length: the model will set thecontext_length(input of the encoder) equal to theprediction_length, if nocontext_lengthis specified;lagsfor a given frequency: these specify an efficient “look back” mechanism, where we concatenate values from the past to the present values as additional features, e.g. for aDay by dayfrequency we’d consider a glance back of[1, 7, 30, ...]or forMinutedata we’d consider[1, 30, 60, 60*24, ...]etc.;- the variety of time features: in our case, this might be

5as we’ll addHourOfDay,DayOfWeek, …, andAgefeatures (see below).

Allow us to check the default lags provided by GluonTS for the given frequency (“hourly”):

from gluonts.time_feature import get_lags_for_frequency

lags_sequence = get_lags_for_frequency(freq)

print(lags_sequence)

>>> [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 23, 24, 25, 47, 48, 49, 71, 72, 73, 95, 96, 97, 119, 120,

121, 143, 144, 145, 167, 168, 169, 335, 336, 337, 503, 504, 505, 671, 672, 673, 719, 720, 721]

Which means that this may look back as much as 721 hours (~30 days) for every time step, as additional features. Nevertheless, the resulting feature vector would find yourself being of size len(lags_sequence)*num_of_variates which for our case might be 34480! This is just not going to work so we’ll use our own sensible lags.

Allow us to also check the default time features which GluonTS provides us:

from gluonts.time_feature import time_features_from_frequency_str

time_features = time_features_from_frequency_str(freq)

print(time_features)

>>> [0x7f3809539240>, 0x7f3809539360>, 0x7f3809539480>, 0x7f38095395a0>]

On this case, there are 4 additional features, namely “hour of day”, “day of week”, “day of month” and “day of yr”. Which means that for every time step, we’ll add these features as a scalar values. For instance, consider the timestamp 2015-01-01 01:00:01. The 4 additional features might be:

from pandas.core.arrays.period import period_array

timestamp = pd.Period("2015-01-01 01:00:01", freq=freq)

timestamp_as_index = pd.PeriodIndex(data=period_array([timestamp]))

additional_features = [

(time_feature.__name__, time_feature(timestamp_as_index))

for time_feature in time_features

]

print(dict(additional_features))

>>> {'hour_of_day': array([-0.45652174]), 'day_of_week': array([0.]), 'day_of_month': array([-0.5]), 'day_of_year': array([-0.5])}

Note that hours and days are encoded as values between [-0.5, 0.5] from GluonTS. For more details about time_features, please see this. Besides those 4 features, we’ll also add an “age” feature as we’ll see in a while in the information transformations.

We now have every part to define the model:

from transformers import InformerConfig, InformerForPrediction

config = InformerConfig(

input_size=num_of_variates,

prediction_length=prediction_length,

context_length=prediction_length * 2,

lags_sequence=[1, 24 * 7],

num_time_features=len(time_features) + 1,

dropout=0.1,

encoder_layers=6,

decoder_layers=4,

d_model=64,

)

model = InformerForPrediction(config)

By default, the model uses a diagonal Student-t distribution (but that is configurable):

model.config.distribution_output

>>> 'student_t'

Define Transformations

Next, we define the transformations for the information, specifically for the creation of the time features (based on the dataset or universal ones).

Again, we’ll use the GluonTS library for this. We define a Chain of transformations (which is a bit comparable to torchvision.transforms.Compose for images). It allows us to mix several transformations right into a single pipeline.

from gluonts.time_feature import TimeFeature

from gluonts.dataset.field_names import FieldName

from gluonts.transform import (

AddAgeFeature,

AddObservedValuesIndicator,

AddTimeFeatures,

AsNumpyArray,

Chain,

ExpectedNumInstanceSampler,

InstanceSplitter,

RemoveFields,

SelectFields,

SetField,

TestSplitSampler,

Transformation,

ValidationSplitSampler,

VstackFeatures,

RenameFields,

)

The transformations below are annotated with comments, to elucidate what they do. At a high level, we’ll iterate over the person time series of our dataset and add/remove fields or features:

from transformers import PretrainedConfig

def create_transformation(freq: str, config: PretrainedConfig) -> Transformation:

remove_field_names = []

if config.num_static_real_features == 0:

remove_field_names.append(FieldName.FEAT_STATIC_REAL)

if config.num_dynamic_real_features == 0:

remove_field_names.append(FieldName.FEAT_DYNAMIC_REAL)

if config.num_static_categorical_features == 0:

remove_field_names.append(FieldName.FEAT_STATIC_CAT)

return Chain(

[RemoveFields(field_names=remove_field_names)]

+ (

[

AsNumpyArray(

field=FieldName.FEAT_STATIC_CAT,

expected_ndim=1,

dtype=int,

)

]

if config.num_static_categorical_features > 0

else []

)

+ (

[

AsNumpyArray(

field=FieldName.FEAT_STATIC_REAL,

expected_ndim=1,

)

]

if config.num_static_real_features > 0

else []

)

+ [

AsNumpyArray(

field=FieldName.TARGET,

expected_ndim=1 if config.input_size == 1 else 2,

),

AddObservedValuesIndicator(

target_field=FieldName.TARGET,

output_field=FieldName.OBSERVED_VALUES,

),

AddTimeFeatures(

start_field=FieldName.START,

target_field=FieldName.TARGET,

output_field=FieldName.FEAT_TIME,

time_features=time_features_from_frequency_str(freq),

pred_length=config.prediction_length,

),

AddAgeFeature(

target_field=FieldName.TARGET,

output_field=FieldName.FEAT_AGE,

pred_length=config.prediction_length,

log_scale=True,

),

VstackFeatures(

output_field=FieldName.FEAT_TIME,

input_fields=[FieldName.FEAT_TIME, FieldName.FEAT_AGE]

+ (

[FieldName.FEAT_DYNAMIC_REAL]

if config.num_dynamic_real_features > 0

else []

),

),

RenameFields(

mapping={

FieldName.FEAT_STATIC_CAT: "static_categorical_features",

FieldName.FEAT_STATIC_REAL: "static_real_features",

FieldName.FEAT_TIME: "time_features",

FieldName.TARGET: "values",

FieldName.OBSERVED_VALUES: "observed_mask",

}

),

]

)

Define InstanceSplitter

For training/validation/testing we next create an InstanceSplitter which is used to sample windows from the dataset (as, remember, we will not pass the complete history of values to the model as a consequence of time- and memory constraints).

The instance splitter samples random context_length sized and subsequent prediction_length sized windows from the information, and appends a past_ or future_ key to any temporal keys in time_series_fields for the respective windows. The instance splitter might be configured into three different modes:

mode="train": Here we sample the context and prediction length windows randomly from the dataset given to it (the training dataset)mode="validation": Here we sample the very last context length window and prediction window from the dataset given to it (for the back-testing or validation likelihood calculations)mode="test": Here we sample the very last context length window only (for the prediction use case)

from gluonts.transform.sampler import InstanceSampler

from typing import Optional

def create_instance_splitter(

config: PretrainedConfig,

mode: str,

train_sampler: Optional[InstanceSampler] = None,

validation_sampler: Optional[InstanceSampler] = None,

) -> Transformation:

assert mode in ["train", "validation", "test"]

instance_sampler = {

"train": train_sampler

or ExpectedNumInstanceSampler(

num_instances=1.0, min_future=config.prediction_length

),

"validation": validation_sampler

or ValidationSplitSampler(min_future=config.prediction_length),

"test": TestSplitSampler(),

}[mode]

return InstanceSplitter(

target_field="values",

is_pad_field=FieldName.IS_PAD,

start_field=FieldName.START,

forecast_start_field=FieldName.FORECAST_START,

instance_sampler=instance_sampler,

past_length=config.context_length + max(config.lags_sequence),

future_length=config.prediction_length,

time_series_fields=["time_features", "observed_mask"],

)

Create DataLoaders

Next, it is time to create the DataLoaders, which permit us to have batches of (input, output) pairs – or in other words (past_values, future_values).

from typing import Iterable

import torch

from gluonts.itertools import Cached, Cyclic

from gluonts.dataset.loader import as_stacked_batches

def create_train_dataloader(

config: PretrainedConfig,

freq,

data,

batch_size: int,

num_batches_per_epoch: int,

shuffle_buffer_length: Optional[int] = None,

cache_data: bool = True,

**kwargs,

) -> Iterable:

PREDICTION_INPUT_NAMES = [

"past_time_features",

"past_values",

"past_observed_mask",

"future_time_features",

]

if config.num_static_categorical_features > 0:

PREDICTION_INPUT_NAMES.append("static_categorical_features")

if config.num_static_real_features > 0:

PREDICTION_INPUT_NAMES.append("static_real_features")

TRAINING_INPUT_NAMES = PREDICTION_INPUT_NAMES + [

"future_values",

"future_observed_mask",

]

transformation = create_transformation(freq, config)

transformed_data = transformation.apply(data, is_train=True)

if cache_data:

transformed_data = Cached(transformed_data)

instance_splitter = create_instance_splitter(config, "train")

stream = Cyclic(transformed_data).stream()

training_instances = instance_splitter.apply(stream)

return as_stacked_batches(

training_instances,

batch_size=batch_size,

shuffle_buffer_length=shuffle_buffer_length,

field_names=TRAINING_INPUT_NAMES,

output_type=torch.tensor,

num_batches_per_epoch=num_batches_per_epoch,

)

def create_backtest_dataloader(

config: PretrainedConfig,

freq,

data,

batch_size: int,

**kwargs,

):

PREDICTION_INPUT_NAMES = [

"past_time_features",

"past_values",

"past_observed_mask",

"future_time_features",

]

if config.num_static_categorical_features > 0:

PREDICTION_INPUT_NAMES.append("static_categorical_features")

if config.num_static_real_features > 0:

PREDICTION_INPUT_NAMES.append("static_real_features")

transformation = create_transformation(freq, config)

transformed_data = transformation.apply(data)

instance_sampler = create_instance_splitter(config, "validation")

testing_instances = instance_sampler.apply(transformed_data, is_train=True)

return as_stacked_batches(

testing_instances,

batch_size=batch_size,

output_type=torch.tensor,

field_names=PREDICTION_INPUT_NAMES,

)

def create_test_dataloader(

config: PretrainedConfig,

freq,

data,

batch_size: int,

**kwargs,

):

PREDICTION_INPUT_NAMES = [

"past_time_features",

"past_values",

"past_observed_mask",

"future_time_features",

]

if config.num_static_categorical_features > 0:

PREDICTION_INPUT_NAMES.append("static_categorical_features")

if config.num_static_real_features > 0:

PREDICTION_INPUT_NAMES.append("static_real_features")

transformation = create_transformation(freq, config)

transformed_data = transformation.apply(data, is_train=False)

instance_sampler = create_instance_splitter(config, "test")

testing_instances = instance_sampler.apply(transformed_data, is_train=False)

return as_stacked_batches(

testing_instances,

batch_size=batch_size,

output_type=torch.tensor,

field_names=PREDICTION_INPUT_NAMES,

)

train_dataloader = create_train_dataloader(

config=config,

freq=freq,

data=multi_variate_train_dataset,

batch_size=256,

num_batches_per_epoch=100,

num_workers=2,

)

test_dataloader = create_backtest_dataloader(

config=config,

freq=freq,

data=multi_variate_test_dataset,

batch_size=32,

)

Let’s check the primary batch:

batch = next(iter(train_dataloader))

for k, v in batch.items():

print(k, v.shape, v.type())

>>> past_time_features torch.Size([256, 264, 5]) torch.FloatTensor

past_values torch.Size([256, 264, 862]) torch.FloatTensor

past_observed_mask torch.Size([256, 264, 862]) torch.FloatTensor

future_time_features torch.Size([256, 48, 5]) torch.FloatTensor

future_values torch.Size([256, 48, 862]) torch.FloatTensor

future_observed_mask torch.Size([256, 48, 862]) torch.FloatTensor

As might be seen, we do not feed input_ids and attention_mask to the encoder (as could be the case for NLP models), but quite past_values, together with past_observed_mask, past_time_features and static_real_features.

The decoder inputs consist of future_values, future_observed_mask and future_time_features. The future_values might be seen because the equivalent of decoder_input_ids in NLP.

We seek advice from the docs for an in depth explanation for every of them.

Forward Pass

Let’s perform a single forward pass with the batch we just created:

outputs = model(

past_values=batch["past_values"],

past_time_features=batch["past_time_features"],

past_observed_mask=batch["past_observed_mask"],

static_categorical_features=batch["static_categorical_features"]

if config.num_static_categorical_features > 0

else None,

static_real_features=batch["static_real_features"]

if config.num_static_real_features > 0

else None,

future_values=batch["future_values"],

future_time_features=batch["future_time_features"],

future_observed_mask=batch["future_observed_mask"],

output_hidden_states=True,

)

print("Loss:", outputs.loss.item())

>>> Loss: -1071.5718994140625

Note that the model is returning a loss. This is feasible because the decoder mechanically shifts the future_values one position to the appropriate in an effort to have the labels. This enables computing a loss between the anticipated values and the labels. The loss is the negative log-likelihood of the anticipated distribution with respect to the bottom truth values and tends to negative infinity.

Also note that the decoder uses a causal mask to not look into the long run because the values it must predict are within the future_values tensor.

Train the Model

It is time to train the model! We’ll use an ordinary PyTorch training loop.

We’ll use the 🤗 Speed up library here, which mechanically places the model, optimizer and dataloader on the suitable device.

from speed up import Accelerator

from torch.optim import AdamW

epochs = 25

loss_history = []

accelerator = Accelerator()

device = accelerator.device

model.to(device)

optimizer = AdamW(model.parameters(), lr=6e-4, betas=(0.9, 0.95), weight_decay=1e-1)

model, optimizer, train_dataloader = accelerator.prepare(

model,

optimizer,

train_dataloader,

)

model.train()

for epoch in range(epochs):

for idx, batch in enumerate(train_dataloader):

optimizer.zero_grad()

outputs = model(

static_categorical_features=batch["static_categorical_features"].to(device)

if config.num_static_categorical_features > 0

else None,

static_real_features=batch["static_real_features"].to(device)

if config.num_static_real_features > 0

else None,

past_time_features=batch["past_time_features"].to(device),

past_values=batch["past_values"].to(device),

future_time_features=batch["future_time_features"].to(device),

future_values=batch["future_values"].to(device),

past_observed_mask=batch["past_observed_mask"].to(device),

future_observed_mask=batch["future_observed_mask"].to(device),

)

loss = outputs.loss

accelerator.backward(loss)

optimizer.step()

loss_history.append(loss.item())

if idx % 100 == 0:

print(loss.item())

>>> -1081.978515625

...

-2877.723876953125

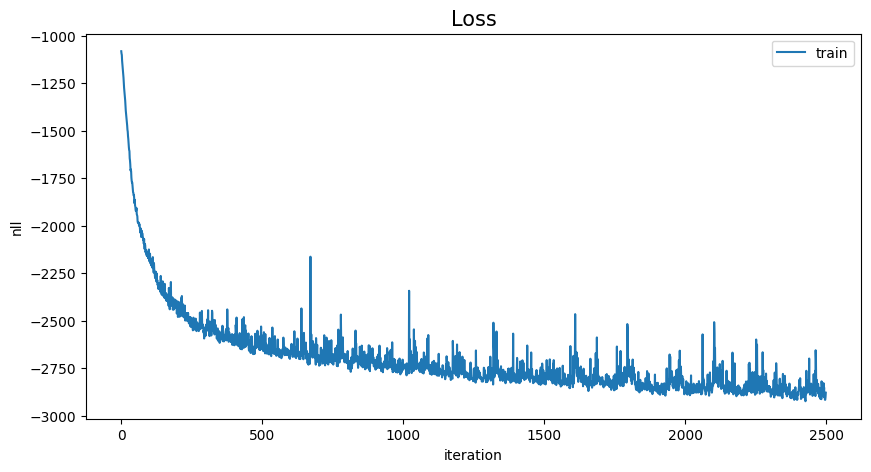

loss_history = np.array(loss_history).reshape(-1)

x = range(loss_history.shape[0])

plt.figure(figsize=(10, 5))

plt.plot(x, loss_history, label="train")

plt.title("Loss", fontsize=15)

plt.legend(loc="upper right")

plt.xlabel("iteration")

plt.ylabel("nll")

plt.show()

Inference

At inference time, it’s beneficial to make use of the generate() method for autoregressive generation, much like NLP models.

Forecasting involves getting data from the test instance sampler, which can sample the very last context_length sized window of values from every time series within the dataset, and pass it to the model. Note that we pass future_time_features, that are known ahead of time, to the decoder.

The model will autoregressively sample a certain variety of values from the anticipated distribution and pass them back to the decoder to return the prediction outputs:

model.eval()

forecasts_ = []

for batch in test_dataloader:

outputs = model.generate(

static_categorical_features=batch["static_categorical_features"].to(device)

if config.num_static_categorical_features > 0

else None,

static_real_features=batch["static_real_features"].to(device)

if config.num_static_real_features > 0

else None,

past_time_features=batch["past_time_features"].to(device),

past_values=batch["past_values"].to(device),

future_time_features=batch["future_time_features"].to(device),

past_observed_mask=batch["past_observed_mask"].to(device),

)

forecasts_.append(outputs.sequences.cpu().numpy())

The model outputs a tensor of shape (batch_size, variety of samples, prediction length, input_size).

On this case, we get 100 possible values for the subsequent 48 hours for every of the 862 time series (for every example within the batch which is of size 1 since we only have a single multivariate time series):

forecasts_[0].shape

>>> (1, 100, 48, 862)

We’ll stack them vertically, to get forecasts for all time-series within the test dataset (just in case there are more time series within the test set):

forecasts = np.vstack(forecasts_)

print(forecasts.shape)

>>> (1, 100, 48, 862)

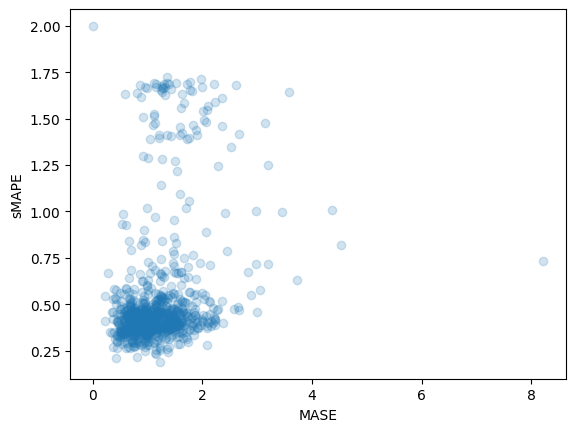

We will evaluate the resulting forecast with respect to the bottom truth out of sample values present within the test set. For that, we’ll use the 🤗 Evaluate library, which incorporates the MASE and sMAPE metrics.

We calculate each metrics for every time series variate within the dataset:

from evaluate import load

from gluonts.time_feature import get_seasonality

mase_metric = load("evaluate-metric/mase")

smape_metric = load("evaluate-metric/smape")

forecast_median = np.median(forecasts, 1).squeeze(0).T

mase_metrics = []

smape_metrics = []

for item_id, ts in enumerate(test_dataset):

training_data = ts["target"][:-prediction_length]

ground_truth = ts["target"][-prediction_length:]

mase = mase_metric.compute(

predictions=forecast_median[item_id],

references=np.array(ground_truth),

training=np.array(training_data),

periodicity=get_seasonality(freq),

)

mase_metrics.append(mase["mase"])

smape = smape_metric.compute(

predictions=forecast_median[item_id],

references=np.array(ground_truth),

)

smape_metrics.append(smape["smape"])

print(f"MASE: {np.mean(mase_metrics)}")

>>> MASE: 1.1913437728068093

print(f"sMAPE: {np.mean(smape_metrics)}")

>>> sMAPE: 0.5322665081607634

plt.scatter(mase_metrics, smape_metrics, alpha=0.2)

plt.xlabel("MASE")

plt.ylabel("sMAPE")

plt.show()

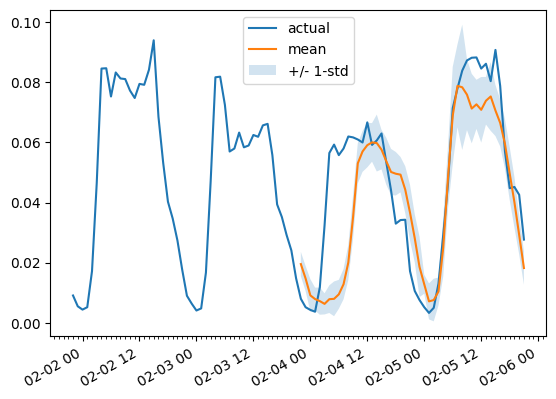

To plot the prediction for any time series variate with respect the bottom truth test data we define the next helper:

import matplotlib.dates as mdates

def plot(ts_index, mv_index):

fig, ax = plt.subplots()

index = pd.period_range(

start=multi_variate_test_dataset[ts_index][FieldName.START],

periods=len(multi_variate_test_dataset[ts_index][FieldName.TARGET]),

freq=multi_variate_test_dataset[ts_index][FieldName.START].freq,

).to_timestamp()

ax.xaxis.set_minor_locator(mdates.HourLocator())

ax.plot(

index[-2 * prediction_length :],

multi_variate_test_dataset[ts_index]["target"][mv_index, -2 * prediction_length :],

label="actual",

)

ax.plot(

index[-prediction_length:],

forecasts[ts_index, ..., mv_index].mean(axis=0),

label="mean",

)

ax.fill_between(

index[-prediction_length:],

forecasts[ts_index, ..., mv_index].mean(0)

- forecasts[ts_index, ..., mv_index].std(axis=0),

forecasts[ts_index, ..., mv_index].mean(0)

+ forecasts[ts_index, ..., mv_index].std(axis=0),

alpha=0.2,

interpolate=True,

label="+/- 1-std",

)

ax.legend()

fig.autofmt_xdate()

For instance:

plot(0, 344)

Conclusion

How will we compare against other models? The Monash Time Series Repository has a comparison table of test set MASE metrics which we will add to:

| Dataset | SES | Theta | TBATS | ETS | (DHR-)ARIMA | PR | CatBoost | FFNN | DeepAR | N-BEATS | WaveNet | Transformer (uni.) | Informer (mv. our) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traffic Hourly | 1.922 | 1.922 | 2.482 | 2.294 | 2.535 | 1.281 | 1.571 | 0.892 | 0.825 | 1.100 | 1.066 | 0.821 | 1.191 |

As might be seen, and maybe surprising to some, the multivariate forecasts are typically worse than the univariate ones, the rationale being the issue in estimating the cross-series correlations/relationships. The extra variance added by the estimates often harms the resulting forecasts or the model learns spurious correlations. We seek advice from this paper for further reading. Multivariate models are inclined to work well when trained on a whole lot of data.

So the vanilla Transformer still performs best here! In the long run, we hope to higher benchmark these models in a central place to ease reproducing the outcomes of several papers. Stay tuned for more!

Resources

We recommend to envision out the Informer docs and the example notebook linked at the highest of this blog post.