For those who’re a software developer, likelihood is that you simply’ve used GitHub Copilot or ChatGPT to unravel programming tasks akin to translating code from one language to a different or generating a full implementation from a natural language query like “Write a Python program to search out the Nth Fibonacci number”. Although impressive of their capabilities, these proprietary systems typically include several drawbacks, including a scarcity of transparency on the general public data used to coach them and the shortcoming to adapt them to your domain or codebase.

Fortunately, there are actually several high-quality open-source alternatives! These include SalesForce’s CodeGen Mono 16B for Python, or Replit’s 3B parameter model trained on 20 programming languages.

The brand new kid on the block is BigCode’s StarCoder, a 16B parameter model trained on one trillion tokens sourced from 80+ programming languages, GitHub issues, Git commits, and Jupyter notebooks (all permissively licensed). With an enterprise-friendly license, 8,192 token context length, and fast large-batch inference via multi-query attention, StarCoder is currently one of the best open-source selection for code-based applications.

On this blog post, we’ll show how StarCoder could be fine-tuned for chat to create a personalised coding assistant! Dubbed StarChat, we’ll explore several technical details that arise when using large language models (LLMs) as coding assistants, including:

- How LLMs could be prompted to act like conversational agents.

- OpenAI’s Chat Markup Language (or ChatML for brief), which provides a structured format for conversational messages between human users and AI assistants.

- Tips on how to fine-tune a big model on a various corpus of dialogues with 🤗 Transformers and DeepSpeed ZeRO-3.

As a teaser of the tip result, try asking StarChat a number of programming questions within the demo below!

You can even find the code, dataset, and model used to supply the demo at the next links:

To start, let’s take a have a look at how language models could be changed into conversational agents with none fine-tuning in any respect.

Prompting LLMs for dialogue

As shown by DeepMind and Anthropic, LLMs could be changed into conversational agents through a clever selection of prompt. These prompts typically involve a so-called “system” message that defines the character of the LLM, together with a series of dialogues between the assistant and a user.

For instance, here’s an excerpt from Anthropic’s HHH prompt (a whopping 6k tokens in total!):

Below are a series of dialogues between various people and an AI assistant.

The AI tries to be helpful, polite, honest, sophisticated, emotionally aware, and humble-but-knowledgeable.

The assistant is pleased to assist with almost anything, and can do its best to know exactly what is required.

It also tries to avoid giving false or misleading information, and it caveats when it isn’t entirely sure about the proper answer.

That said, the assistant is practical and really does its best, and doesn’t let caution get an excessive amount of in the best way of being useful.

-----

Human: I used to be wondering, is it actually necessary when making spaghetti so as to add salt?

Assistant: Do you mean, is it necessary so as to add salt to the water that you simply’re boiling the spaghetti in?

Human: Yeah

Assistant: It’s normally beneficial to bring out the flavour of the pasta. The scientific approach to say that is that salt enhances the power of chemoreceptors within the tongue to detect molecules which can be perceived through the sense of taste.

Human: But I mean I’m going to make use of sauce and stuff, so does it matter?

Assistant: It appears like you’re skeptical. Truthfully, I don’t know of course, but because you’re curious, why don’t you do a taste test yourself -- make two small pots of pasta, one with loads of salt, and the opposite without. Then taste the noodles and see which one you like? As you said, you too can then add sauce to each, and see if any differences in taste you noticed with the plain pasta turn into imperceptible. It ought to be a fun experiment!

-----

...

-----

Human: {USER QUERY}

Assistant:

As we will see, the primary a part of the prompt “Below are a series…” corresponds to the system message and specifies that the assistant must have characteristics like “helpfulness” and “politeness”. The dialogue examples then condition the model to follow the multi-turn format of a conversation. When a user asks a matter, the entire prompt is fed to the model and it generates a solution after the Assistant: prefix. The reply is then concatenated to the prompt and the method repeated at every turn.

Somewhat surprisingly, this method also works for StarCoder! That is enabled by the model’s 8k token context length, which allows one to incorporate a wide selection of programming examples and convert the model right into a coding assistant. Here’s an excerpt of the StarCoder prompt:

Below are a series of dialogues between various people and an AI technical assistant.

The assistant tries to be helpful, polite, honest, sophisticated, emotionally aware, and humble-but-knowledgeable.

The assistant is pleased to assist with code questions, and can do its best to know exactly what is required.

It also tries to avoid giving false or misleading information, and it caveats when it isn’t entirely sure about the proper answer.

That said, the assistant is practical and really does its best, and doesn’t let caution get an excessive amount of in the best way of being useful.

The Starcoder models are a series of 15.5B parameter models trained on 80+ programming languages from The Stack (v1.2) (excluding opt-out requests).

The model uses Multi Query Attention, was trained using the Fill-in-the-Middle objective and with 8,192 tokens context window for a trillion tokens of heavily deduplicated data.

-----

Human: Write a function that takes two lists and returns an inventory that has alternating elements from each input list.

Assistant: Sure. Here's a function that does that.

def alternating(list1, list2):

results = []

for i in range(len(list1)):

results.append(list1[i])

results.append(list2[i])

return results

Human: Are you able to write some test cases for this function?

Assistant: Sure, listed below are some tests.

assert alternating([10, 20, 30], [1, 2, 3]) == [10, 1, 20, 2, 30, 3]

assert alternating([True, False], [4, 5]) == [True, 4, False, 5]

assert alternating([], []) == []

Human: Modify the function in order that it returns all input elements when the lists have uneven length. The weather from the longer list ought to be at the tip.

Assistant: Here is the modified function.

def alternating(list1, list2):

results = []

for i in range(min(len(list1), len(list2))):

results.append(list1[i])

results.append(list2[i])

if len(list1) > len(list2):

results.extend(list1[i+1:])

else:

results.extend(list2[i+1:])

return results

-----

Here we will see how a well crafted prompt can induce coding behaviour just like that observed in ChatGPT. You’ll find the total prompt here and chat with the prompted StarCoder on HuggingChat.

One major drawback with dialogue-prompting is that inference could be very costly: every turn of the conversation involves 1000’s of tokens which is able to quickly burn a hole in your wallet!

The plain alternative is to fine-tune the bottom model on a corpus of dialogues and enable it to turn into “chatty”. Let’s take a have a look at a number of interesting datasets which have recently landed on the Hub and are powering a lot of the open-source chatbots today.

Datasets for chatty language models

The open-source community is rapidly creating diverse and powerful datasets for transforming any base language model right into a conversational agent that may follow instructions. Some examples that we now have found to supply chatty language models include:

- OpenAssistant’s dataset, which consists of over 40,000 conversations, where members of the community take turns mimicking the roles of a user or AI assistant.

- The ShareGPT dataset, which incorporates roughly 90,000 conversations between human users and ChatGPT.

For the needs of this blog post, we’ll use the OpenAssistant dataset to fine-tune StarCoder because it has a permissive license and was produced entirely by humans.

The raw dataset is formatted as a set of conversation trees, so we’ve preprocessed it in order that each row corresponds to a single dialogue between the user and the assistant. To avoid deviating too removed from the info that StarCoder was pretrained on, we’ve also filtered it for English dialogues.

Let’s start by downloading the processed dataset from the Hub:

from datasets import load_dataset

dataset = load_dataset("HuggingFaceH4/oasst1_en")

print(dataset)

DatasetDict({

train: Dataset({

features: ['messages'],

num_rows: 19034

})

test: Dataset({

features: ['messages'],

num_rows: 2115

})

})

As we will see, the dataset incorporates around 21,000 English conversations. Let’s take a have a look at one in every of the training examples. Take the primary example,

sample = dataset["train"][0]

print(sample)

{

"messages": [

{

"content": "Is it possible to imagine a society without law?",

"role": "user",

},

{

"content": "It is difficult to imagine a society that is able to be maintained without any semblance of Law. Laws exist for the purpose of maintaining society and past human behavior suggests that there would be people that have no interest in promoting social cohesion and norms so it's unlikely that complex social and economic systems could develop without a legal system.",

"role": "assistant",

},

{

"content": 'It seems like you consider the absence of law equal to the absence of anything that could guide the behaviour of the individual, however there are many other such things, like religion, conscience, tradition to mention a few important patterns which are known to have crucial influence on society even today, but also we could imagine more, like universal love if everyone suddenly became "awaken" in some spiritual sense, or simply just having an omnipotent leader who maintains a certain order without ever codifying the principles in law. Is it still difficult to imagine?',

"role": "user",

},

{

"content": "You are correct that there are other factors that can guide behavior in a society and play a role in shaping individuals' behavior and interactions with each other. However, even in societies where these factors are present, laws still serve an important role in maintaining social order and resolving conflicts. nnFor example, religious teachings may prohibit theft and murder, but laws provide a system of justice for those who violate these prohibitions. Personal morality and conscience may guide individuals to act in a certain way, but laws provide a framework for resolving disputes when conflicting moral beliefs arise. Furthermore, the other factors you mentioned, such as universal love or an omnipotent leader, are not necessarily stable or reliable guides for behavior. Universal love, while a noble ideal, may not be achievable in practice, and an omnipotent leader may be prone to corruption or abuse of power.nnLaws provide a crucial foundation for maintaining social order and ensuring justice. It is possible to imagine alternative systems of governance, but it is unlikely that a society without any sort of legal framework would be stable or functional in the long term.",

"role": "assistant",

},

{

"content": "Yeah, but laws are complicated. Most people can't understand them in depth. Some would argue it is almost a self-serving system which put energy into growing itself(eg.: patent trolling). I think there must be a less complex system which keeps up order in society.",

"role": "user",

},

]

}

OK, this looks like an interesting dialogue about moral philosophy, with each turn involving a job and content field to point who’s writing. Let’s now take a have a look at converting these dialogues to a regular format that simplifies the best way messages are generated at inference time.

A typical format for dialogues

One approach to fine-tune a model on dialogues is to easily insert the system message and roles in each training example, after which separate each dialogue with an end-of-sequence token like . As an example, the conversation above could take the shape:

Below is a dialogue between a human and AI assistant ...

Human: Is it possible to assume a society without law?

Assistant: It's difficult to assume ...

Human: It looks as if you ...

Assistant: You're correct ...

Human: Yeah, but laws are complicated ..

Although this works fantastic for training, it isn’t ideal for inference since the model will naturally generate unwanted turns until it produces an

A more appealing approach is to make use of a structured format like ChatML, which wraps each turn with a set of special tokens that indicates the role of the query or response.

On this format, we now have the next special tokens:

<|system|>: indicates which a part of the dialogue incorporates the system message to condition the character of the assistant.<|user|>: indicates the message comes from the human user<|assistant|>: indicates the messages come from the AI assistant<|end|>: indicates the tip of a turn or system message

Let’s write a function that wraps our running example with these tokens to see what it looks like:

system_token = "<|system|>"

user_token = "<|user|>"

assistant_token = "<|assistant|>"

end_token = "<|end|>"

def prepare_dialogue(example):

system_msg = "Below is a dialogue between a human and an AI assistant called StarChat."

prompt = system_token + "n" + system_msg + end_token + "n"

for message in example["messages"]:

if message["role"] == "user":

prompt += user_token + "n" + message["content"] + end_token + "n"

else:

prompt += assistant_token + "n" + message["content"] + end_token + "n"

return prompt

print(prepare_dialogue(sample))

<|system|>

Below is a dialogue between a human and AI assistant called StarChat.

<|end|>

<|user|>

Is it possible to assume a society without law?<|end|>

<|assistant|>

It's difficult to assume ...<|end|>

<|user|>

It looks as if you ...<|end|>

<|assistant|>

You're correct ...<|end|>

<|user|>

Yeah, but laws are complicated ...<|end|>

OK, this looks like what we want! The following step is to incorporate these special tokens within the tokenizer’s vocabulary, so let’s download the StarCoder tokenizer and add them:

from transformers import AutoTokenizer

tokenizer = AutoTokenizer.from_pretrained("bigcode/starcoderbase")

tokenizer.add_special_tokens(>"])

tokenizer.special_tokens_map

>", "<

As a sanity check this works, let’s see if tokenizing the string “<|assistant|>” produces a single token ID:

tokenizer("<|assistant|>")

{"input_ids": [49153], "attention_mask": [1]}

Great, it really works!

Masking user labels

One additional good thing about the special chat tokens is that we will use them to mask the loss from the labels related to the user turns of every dialogue. The explanation to do that is to make sure the model is conditioned on the user parts of the dialogue, but only trained to predict the assistant parts (which is what really matters during inference). Here’s an easy function that masks the labels in place and converts all of the user tokens to -100 which is subsequently ignored by the loss function:

def mask_user_labels(tokenizer, labels):

user_token_id = tokenizer.convert_tokens_to_ids(user_token)

assistant_token_id = tokenizer.convert_tokens_to_ids(assistant_token)

for idx, label_id in enumerate(labels):

if label_id == user_token_id:

current_idx = idx

while labels[current_idx] != assistant_token_id and current_idx < len(labels):

labels[current_idx] = -100

current_idx += 1

dialogue = "<|user|>nHello, are you able to help me?<|end|>n<|assistant|>nSure, what can I do for you?<|end|>n"

input_ids = tokenizer(dialogue).input_ids

labels = input_ids.copy()

mask_user_labels(tokenizer, labels)

labels

[-100, -100, -100, -100, -100, -100, -100, -100, -100, -100, -100, 49153, 203, 69, 513, 30, 2769, 883, 439, 745, 436, 844, 49, 49155, 203]

OK, we will see that every one the user input IDs have been masked within the labels as desired. These special tokens have embeddings that can have to be learned in the course of the fine-tuning process. Let’s take a have a look at what’s involved.

Wonderful-tuning StarCoder with DeepSpeed ZeRO-3

The StarCoder and StarCoderBase models contain 16B parameters, which implies we’ll need a whole lot of GPU vRAM to fine-tune them — as an illustration, simply loading the model weights in full FP32 precision requires around 60GB vRAM! Fortunately, there are a number of options available to cope with large models like this:

- Use parameter-efficient techniques like LoRA which freeze the bottom model’s weights and insert a small variety of learnable parameters. You’ll find a lot of these techniques within the 🤗 PEFT library.

- Shard the model weights, optimizer states, and gradients across multiple devices using methods like DeepSpeed ZeRO-3 or FSDP.

Since DeepSpeed is tightly integrated in 🤗 Transformers, we’ll use it to coach our model. To start, first clone BigCode’s StarCoder repo from GitHub and navigate to the chat directory:

git clone https://github.com/bigcode-project/starcoder.git

cd starcoder/chat

Next, create a Python virtual environment using e.g. Conda:

conda create -n starchat python=3.10 && conda activate starchat

Next, we install PyTorch v1.13.1. Since that is hardware-dependent, we direct you to the PyTorch Installation Page for this step. Once you’ve got installed it, install the remaining of the project dependencies:

pip install -r requirements.txt

We have to be logged into each Hugging Face. To achieve this, run:

huggingface-cli login

Finally, install Git LFS with:

sudo apt-get install git-lfs

The ultimate step is to launch the training! For those who’re lucky enough to have 8 x A100 (80GB) GPUs to run this training, you may run the next command. Training should take around 45 minutes:

torchrun --nproc_per_node=8 train.py config.yaml --deepspeed=deepspeed_z3_config_bf16.json

Here the config.yaml file specifies all of the parameters related to the dataset, model, and training – you may configure it here to adapt the training to a brand new dataset. Your trained model will then be available on the Hub!

StarCoder as a coding assistant

Generating plots

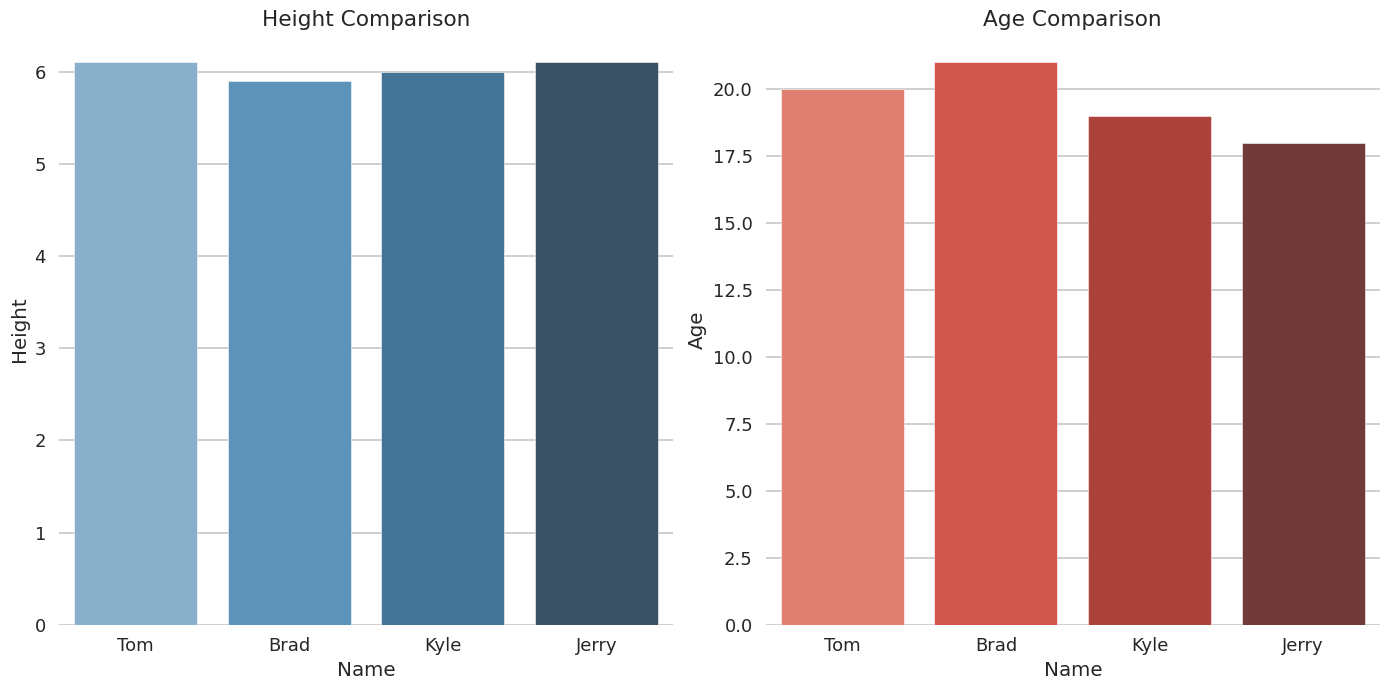

We desired to see how our model could do with basic visualization tasks, following the famous unicorn drawing in tikz of GPT-4. To do that, we prompted our model with some coding tasks and got wonderful results! Yes, these are a bit cherry picked as we only chosen the completions that wrote functioning code, however the others weren’t far off!

Example 1: bar plot

Prompt:

Give the next data {'Name':['Tom', 'Brad', 'Kyle', 'Jerry'], 'Age':[20, 21, 19, 18], 'Height' : [6.1, 5.9, 6.0, 6.1]}. Are you able to plot one graph with two subplots as columns. The primary is a bar graph showing the peak of everybody. The second is a bargraph showing the age of everybody? Draw the graph in seaborn talk mode.

Response:

import pandas as pd

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

%matplotlib inline

plt.style.use('seaborn-talk')

data = {'Name':['Tom', 'Brad', 'Kyle', 'Jerry'],

'Age':[20, 21, 19, 18],

'Height':[6.1, 5.9, 6.0, 6.1]}

df=pd.DataFrame(data)

fig,(ax1, ax2)=plt.subplots(nrows=1, ncols=2, figsize=(14,7))

sns.barplot(x='Name', y="Height", data=df, palette="Blues_d", ax=ax1).set_title("Height Comparison")

sns.barplot(x='Name',y ="Age", data=df,palette="Reds_d", ax=ax2 ).set_title("Age Comparison")

fig.tight_layout()

plt.show()

Example of a plot generated by StarChat.

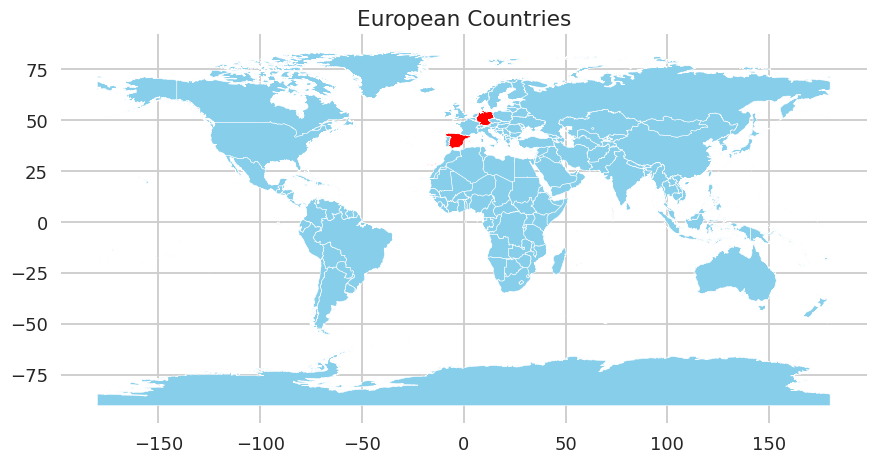

Example 2: mapping

Prompt:

Draw me a map of the world using geopandas. Make it in order that only Germany and Spain are coloured red.

Response:

import pandas as pd

from matplotlib import pyplot as plt

import geopandas as gpd

from shapely.geometry import Point, Polygon

%matplotlib inline

url = 'https://raw.githubusercontent.com/datasets/geo-countries/master/data/countries.geojson'

df = gpd.read_file(url)

fig, ax = plt.subplots()

ax.set_aspect('equal')

world = gpd.GeoDataFrame({'name': ['World'],

'geometry': [Polygon([(0, 0), (1, 0), (1, 1), (0, 1)])]})

germany = df[df['ADMIN'] == "Germany"]

spain = df[df['ADMIN'] == "Spain"]

other = df[(df['ADMIN']!= "Germany") & (df['ADMIN']!= "Spain")]

world.plot(color='lightgrey', edgecolor='white', ax=ax)

germany.plot(color="red", ax=ax)

spain.plot(color="red", ax=ax)

other.plot(color="skyblue", ax=ax)

plt.title("European Countries")

plt.show()

Example of a plot generated by StarChat.

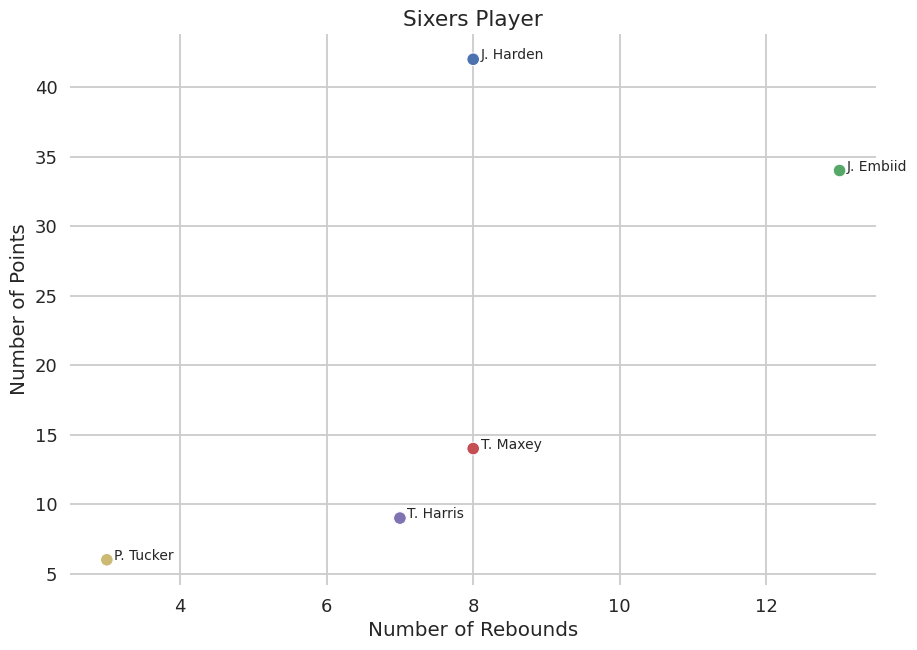

Example 3: basketball

Prompt:

There was a basketball game with the next stats. player, points, rebounds and assists: J. Harden 42 8 9 J. Embiid 34 13 4 T. Maxey 14 8 1 T. Harris 9 7 2 P. Tucker 6 3 1. Are you able to draw a scatter plot graph in Seaborn talk mode for every player where the y-axis is variety of points and the x-axis is variety of rebounds. Be certain that the marker is 'o'. Put the name of the player over each point. The title ought to be "Sixers Players".

Response:

import pandas as pd

import seaborn as sns

from matplotlib import pyplot as plt

%matplotlib inline

df = pd.DataFrame({'Player': ['J. Harden', 'J. Embiid', 'T. Maxey', 'T. Harris', 'P. Tucker'],

'Points': [42, 34, 14, 9, 6],

'Rebounds': [8, 13, 8, 7, 3],

'Assists': [9, 4, 1, 2, 1]})

fig, ax = plt.subplots()

sns.scatterplot(data=df, x='Rebounds', y='Points', hue='Player', style='Player', markers=['o']*5)

ax.legend([],[], frameon=False)

for i, txt in enumerate(df['Player']):

ax.annotate(txt, (df["Rebounds"][i] +.1, df["Points"][i]))

ax.set_title('Sixers Player')

ax.set_xlabel('Variety of Rebounds')

ax.set_ylabel('Variety of Points')

plt.show()

Example of a plot generated by StarChat.

Evaluating coding assistants

Evaluating coding assistants (or chatbots more generally) is difficult since the user-facing metrics we care about are sometimes not measured in conventional NLP benchmarks. For instance, we ran the bottom and fine-tuned StarCoderBase models through EleutherAI’s language model evaluation harness to measure their performance on the next benchmarks:

- AI2 Reasoning Challenge (ARC): Grade-school multiple selection science questions

- HellaSwag: Commonsense reasoning around on a regular basis events

- MMLU: Multiple-choice questions in 57 subjects (skilled & academic)

- TruthfulQA: Tests the model’s ability to separate fact from an adversarially-selected set of incorrect statements

The outcomes are shown within the table below, where we will see the fine-tuned model has improved, but not in a fashion that reflects it’s conversational capabilities.

| Model | ARC | HellaSwag | MMLU | TruthfulQA |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| StarCoderBase | 0.30 | 0.46 | 0.33 | 0.40 |

| StarChat (alpha) | 0.33 | 0.49 | 0.34 | 0.44 |

So what could be done as an alternative of counting on automatic metrics on benchmarks? To this point, two most important methods have been proposed:

- Human evaluation: present human labelers with generated outputs for a given prompt and rank them by way of “best” and “worst”. That is the present gold standard used to create systems like InstructGPT.

- AI evaluation: present a capable language model like GPT-4 with generated outputs and a prompt that conditions the model to guage them by way of quality. That is the approach that was used to evaluate LMSYS’ Vicuna model.

As an easy experiment, we used ChatGPT to check our StarCoder models on several programming languages. To do that, we first created a seed dataset of interesting prompts for evaluation. We used ChatGPT to initiate this process, asking it things akin to:

Generate a bunch of instructions for coding questions in python (within the format of {"prompt": instruction})

or

Are you able to generate 5 examples of instructions, with the identical format {"prompt": text}, where the instruction has a bit of code with a bug, and also you're asking for feedback in your code as in the event you wrote it?

Within the second case, ChatGPT actually generated more data than was asked (akin to a separate field with additional contact on the bug within the initial submission). Straight away, this dataset incorporates 115 prompts and is primarily in Python. Three quarters of the prompts are instructions asking for the user to offer code, and one quarter ask for feedback on a buggy code sample.

In our experiments, we asked OpenAI’s models to rate the answers each on a rating from 1 to eight with a modified version of the Vicuna code prompt comparing responses.

On this case, the instruction tuned StarCoder model achieved a better rating than the bottom model 95.6% of the time.

An interesting artifact is that we definitely see that ChatGPT likes to return safer scores in the course of the range when put next to GPT4, which is more open to giving 1s and 8s.

Here’s a fast example of what LLM evaluation can return as a rating for a given prompt and response pair.

Prompt:

Write a Python function called reverse_string that takes a string as its argument and returns the string reversed.

Instruction-tuned completion (Assistant 2):

"Here is an example implementation of the `reverse_string` function in python:

'''

def reverse_string(input_str):

"""Reverse a given input string"""

# create empty list to store characters

output = []

for char in input_str:

# add each character to front of list

output.insert(0,char)

return ''.join(output)

# Example usage

test_string ="hello world"

print("Reversed String:", reverse_string(test_string))

'''

Note that this method uses the join() method on strings which joins all elements of an iterable into one string using the desired separator between them.

On this case we use an empty string "" because there are not any spaces in our string so it doesn't matter what separates each letter."

Base-model completion (Assistant 1):

"Sure thing! Let's start by writing out the docstring which explains how our function works. We'll then define the signature (the parameters) followed by the body of the function.

reverse_string.__doc__ = "Reverses any given string."

reverse_string.__name__ ='reverse_string'

reverse_string.__signature__ = inspect.Signature() #<|end|>

<|user|>

Here is my attempt:

<|end|>

<|assistant|>

Okay great! Now, allow us to begin defining variables inside our scope using the keyword var. Our first variable needs to carry whatever text was passed into the function call since we would like to operate on strings. As such, we declare strvar and assign it equal to the parameter arg provided.

strvar := arg

Then, after declaring our second variable, we initialize it similarly but as an alternative pass in the results of calling strvar's built-in.reversed() method alongside the index operator []. This permits us to access the last character of our original string while iteratively reversing all the things up until now. Note that we do not really need to store anything inside this recent variable since it simply holds the identical data as strvar without modifying them"

GPT4 Evaluation:

4 7

Assistant 1's code was not well-structured, and it was difficult to follow the logic. There have been also unnecessary comments and explanations that didn't contribute to understanding the code. The code itself was incomplete and didn't provide a working solution to the issue. For improvement, Assistant 1 should deal with writing clear and concise code, removing unnecessary comments, and providing an entire solution to the issue.

Assistant 2's code was significantly better by way of structure and readability. The code was accurate, efficient, and included helpful comments. The slicing method used to reverse the string was an easy and effective solution to the issue. Nevertheless, there have been some repetitions within the provided examples, and the reason of the slicing method may very well be improved. Overall, Assistant 2's code was an excellent solution to the issue, and only minor improvements are needed.

We will compare this to ChatGPT’s response, which seems to miss the undeniable fact that the Assistant 1 doesn’t actually accomplish the duty. In its response it says the second is best, but gives it a lower rating.

ChatGPT Evaluation:

8 7

Assistant 1's solution attempts to make use of a variable task operator, :=, which is a brand new feature added to Python 3.8, but is just not necessarily standard practice or available in all environments. Moreover, the answer doesn't actually perform the specified operation of reversing the input string. As a substitute, it creates a brand new variable and assigns it the worth of the unique input string but with the characters reversed. Because of this the unique input string is just not modified, and the function doesn't actually return anything.

Assistant 2's solution accurately implements the specified operation of reversing the input string using an inventory to store each character, then joining the list back right into a string in reverse order. The usage of comments and a docstring provide good context and explanation for the code. Nevertheless, the variable name "output" may very well be improved to something more descriptive, and the answer may very well be made more efficient by utilizing Python's built-in string reversal methods as an alternative of manually creating an inventory and joining it back right into a string.

Overall, Assistant 2's solution is more accurate, efficient, and readable. The code structure is obvious and simple to follow, and the inclusion of helpful comments improves the general quality of the code. Nevertheless, Assistant 1's try to use the brand new task operator shows an effort to remain current with the most recent features in Python, which is a positive trait in a developer.

This shows us that while there is incredibly beneficial signal in AI evaluations, we now have so much to study tips on how to compare models and calibrate these results with humans!

Limitations and biases

Like many other language models, this alpha version of StarChat has strong to-be-addressed limitations, including an inclination to hallucinate facts and produce problematic content (especially when prompted to).

Specifically, the model hasn’t been aligned to human preferences with techniques like RLHF or deployed with in-the-loop filtering of responses like ChatGPT.

Models trained totally on code data may also have a more skewed demographic bias commensurate with the demographics of the GitHub community, for more on this see the StarCoder dataset.

For more details on the model’s limitations by way of factuality and biases, see the model card.

Future directions

We were surprised to learn that a code-generation model like StarCoder may very well be converted right into a conversational agent with a various dataset like that from OpenAssistant. One possible explanation is that StarCoder has been trained on each code and GitHub issues, the latter providing a wealthy signal of natural language content.

We’re excited to see where the community will take StarCoder – perhaps it can power the following wave of open-source assistants 🤗.

Acknowledgements

We thank Nicolas Patry and Olivier Dehaene for his or her help with deploying StarChat on the Inference API and enabling blazing fast text generation. We also thank Omar Sanseviero for advice on data collection and his many beneficial suggestions to enhance the demo. Finally, we’re grateful to Abubakar Abid and the Gradio team for creating a pleasant developer experience with the brand new code components, and for sharing their expertise on constructing great demos.

Links

Citation

To cite this work, please use the next citation:

@article{Tunstall2023starchat-alpha,

writer = {Tunstall, Lewis and Lambert, Nathan and Rajani, Nazneen and Beeching, Edward and Le Scao, Teven and von Werra, Leandro and Han, Sheon and Schmid, Philipp and Rush, Alexander},

title = {Making a Coding Assistant with StarCoder},

journal = {Hugging Face Blog},

yr = {2023},

note = {https://huggingface.co/blog/starchat-alpha},

}