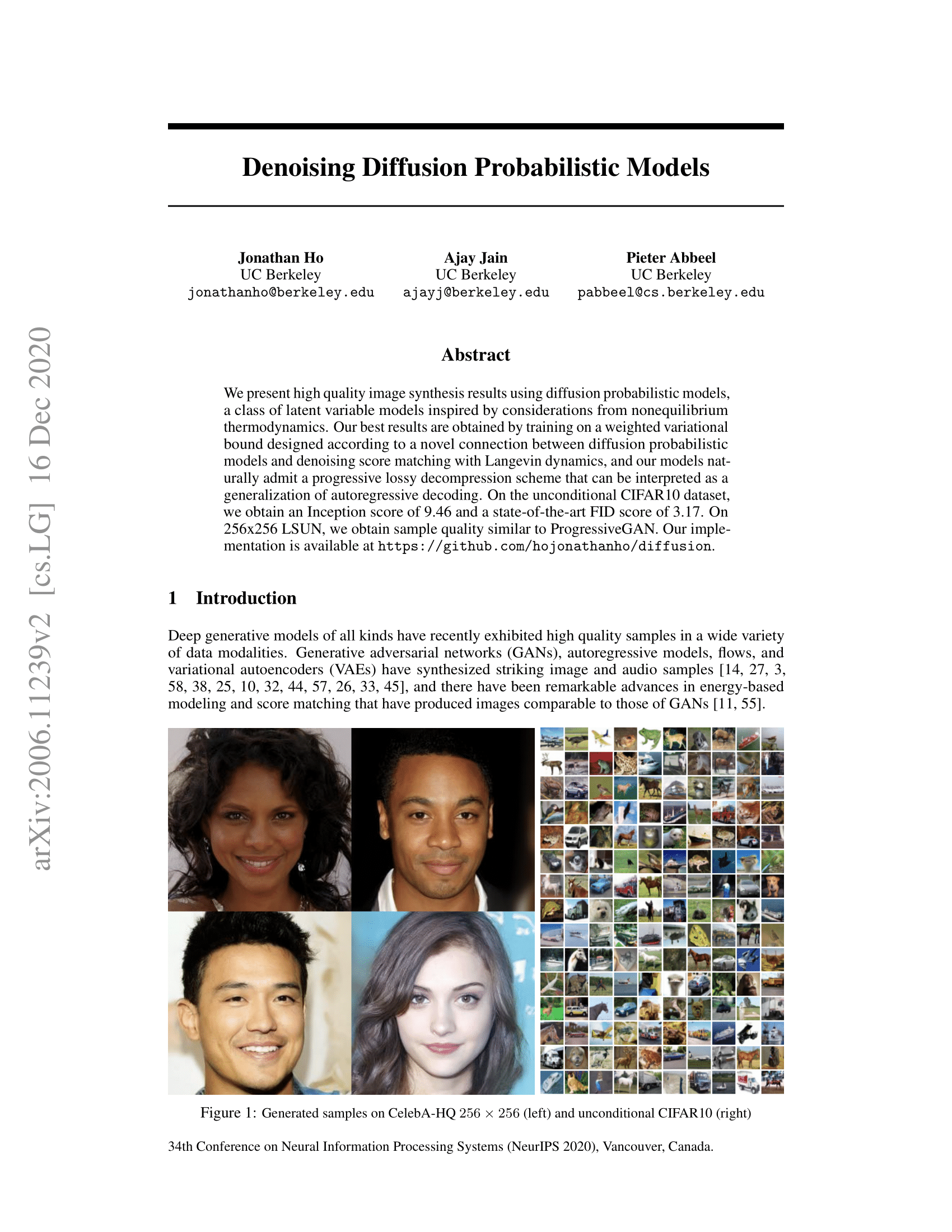

On this blog post, we’ll take a deeper look into Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Models (also often known as DDPMs, diffusion models, score-based generative models or just autoencoders) as researchers have been capable of achieve remarkable results with them for (un)conditional image/audio/video generation. Popular examples (on the time of writing) include GLIDE and DALL-E 2 by OpenAI, Latent Diffusion by the University of Heidelberg and ImageGen by Google Brain.

We’ll go over the unique DDPM paper by (Ho et al., 2020), implementing it step-by-step in PyTorch, based on Phil Wang’s implementation – which itself is predicated on the original TensorFlow implementation. Note that the concept of diffusion for generative modeling was actually already introduced in (Sohl-Dickstein et al., 2015). Nevertheless, it took until (Song et al., 2019) (at Stanford University), after which (Ho et al., 2020) (at Google Brain) who independently improved the approach.

Note that there are several perspectives on diffusion models. Here, we employ the discrete-time (latent variable model) perspective, but you’ll want to try the opposite perspectives as well.

Alright, let’s dive in!

from IPython.display import Image

Image(filename='assets/78_annotated-diffusion/ddpm_paper.png')

We’ll install and import the required libraries first (assuming you’ve got PyTorch installed).

!pip install -q -U einops datasets matplotlib tqdm

import math

from inspect import isfunction

from functools import partial

%matplotlib inline

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from tqdm.auto import tqdm

from einops import rearrange, reduce

from einops.layers.torch import Rearrange

import torch

from torch import nn, einsum

import torch.nn.functional as F

What’s a diffusion model?

A (denoising) diffusion model is not that complex in the event you compare it to other generative models similar to Normalizing Flows, GANs or VAEs: all of them convert noise from some easy distribution to a knowledge sample. This can be the case here where a neural network learns to progressively denoise data ranging from pure noise.

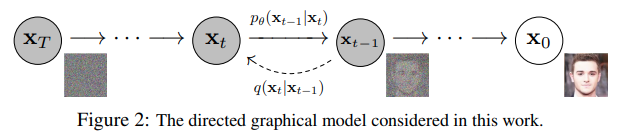

In a bit more detail for images, the set-up consists of two processes:

- a hard and fast (or predefined) forward diffusion process of our selecting, that progressively adds Gaussian noise to a picture, until you find yourself with pure noise

- a learned reverse denoising diffusion process , where a neural network is trained to progressively denoise a picture ranging from pure noise, until you find yourself with an actual image.

Each the forward and reverse process indexed by occur for some variety of finite time steps (the DDPM authors use ). You begin with where you sample an actual image out of your data distribution (for example a picture of a cat from ImageNet), and the forward process samples some noise from a Gaussian distribution at every time step , which is added to the image of the previous time step. Given a sufficiently large and a well behaved schedule for adding noise at every time step, you find yourself with what is known as an isotropic Gaussian distribution at via a gradual process.

In additional mathematical form

Let’s write this down more formally, as ultimately we want a tractable loss function which our neural network must optimize.

Let be the true data distribution, say of “real images”. We are able to sample from this distribution to get a picture, . We define the forward diffusion process which adds Gaussian noise at every time step , in response to a known variance schedule as

Recall that a standard distribution (also called Gaussian distribution) is defined by 2 parameters: a mean and a variance . Mainly, each latest (barely noisier) image at time step is drawn from a conditional Gaussian distribution with and , which we are able to do by sampling after which setting .

Note that the aren’t constant at every time step (hence the subscript) — in reality one defines a so-called “variance schedule”, which will be linear, quadratic, cosine, etc. as we are going to see further (a bit like a learning rate schedule).

So ranging from , we find yourself with , where is pure Gaussian noise if we set the schedule appropriately.

Now, if we knew the conditional distribution , then we could run the method in reverse: by sampling some random Gaussian noise , after which progressively “denoise” it in order that we find yourself with a sample from the true distribution .

Nevertheless, we do not know . It’s intractable because it requires knowing the distribution of all possible images to be able to calculate this conditional probability. Hence, we’ll leverage a neural network to approximate (learn) this conditional probability distribution, let’s call it , with being the parameters of the neural network, updated by gradient descent.

Okay, so we want a neural network to represent a (conditional) probability distribution of the backward process. If we assume this reverse process is Gaussian as well, then recall that any Gaussian distribution is defined by 2 parameters:

- a mean parametrized by ;

- a variance parametrized by ;

so we are able to parametrize the method as

where the mean and variance are also conditioned on the noise level .

Hence, our neural network must learn/represent the mean and variance. Nevertheless, the DDPM authors decided to keep the variance fixed, and let the neural network only learn (represent) the mean of this conditional probability distribution. From the paper:

First, we set to untrained time dependent constants. Experimentally, each and (see paper) had similar results.

This was then later improved within the Improved diffusion models paper, where a neural network also learns the variance of this backwards process, besides the mean.

So we proceed, assuming that our neural network only must learn/represent the mean of this conditional probability distribution.

Defining an objective function (by reparametrizing the mean)

To derive an objective function to learn the mean of the backward process, the authors observe that the mixture of and will be seen as a variational auto-encoder (VAE) (Kingma et al., 2013). Hence, the variational lower sure (also called ELBO) will be used to reduce the negative log-likelihood with respect to ground truth data sample (we consult with the VAE paper for details regarding ELBO). It seems that the ELBO for this process is a sum of losses at every time step , . By construction of the forward process and backward process, each term (apart from ) of the loss is definitely the KL divergence between 2 Gaussian distributions which will be written explicitly as an L2-loss with respect to the means!

A direct consequence of the constructed forward process , as shown by Sohl-Dickstein et al., is that we are able to sample at any arbitrary noise level conditioned on (since sums of Gaussians can be Gaussian). This could be very convenient: we need not apply repeatedly to be able to sample .

Now we have that

with and . Let’s consult with this equation because the “nice property”. This implies we are able to sample Gaussian noise and scale it appropriately and add it to to get directly. Note that the are functions of the known variance schedule and thus are also known and will be precomputed. This then allows us, during training, to optimize random terms of the loss function (or in other words, to randomly sample during training and optimize ).

One other fantastic thing about this property, as shown in Ho et al. is that one can (after some math, for which we refer the reader to this excellent blog post) as an alternative reparametrize the mean to make the neural network learn (predict) the added noise (via a network ) for noise level within the KL terms which constitute the losses. Which means that our neural network becomes a noise predictor, reasonably than a (direct) mean predictor. The mean will be computed as follows:

The ultimate objective function then looks as follows (for a random time step given ):

Here, is the initial (real, uncorrupted) image, and we see the direct noise level sample given by the fixed forward process. is the pure noise sampled at time step , and is our neural network. The neural network is optimized using an easy mean squared error (MSE) between the true and the anticipated Gaussian noise.

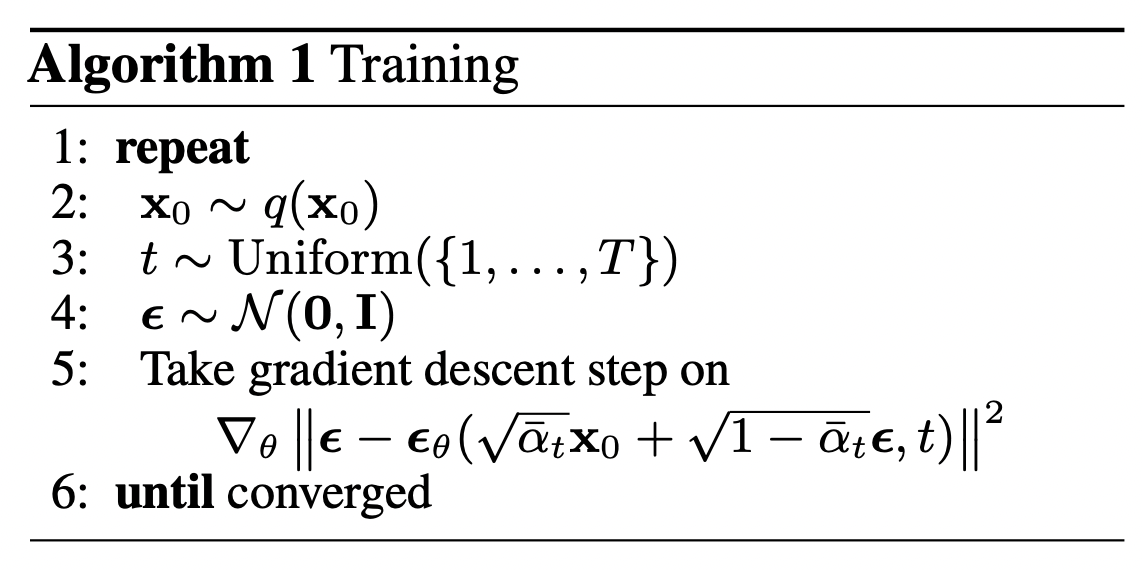

The training algorithm now looks as follows:

In other words:

- we take a random sample from the true unknown and possibily complex data distribution

- we sample a noise level uniformly between and (i.e., a random time step)

- we sample some noise from a Gaussian distribution and corrupt the input by this noise at level (using the good property defined above)

- the neural network is trained to predict this noise based on the corrupted image (i.e. noise applied on based on known schedule )

In point of fact, all of this is finished on batches of information, as one uses stochastic gradient descent to optimize neural networks.

The neural network

The neural network needs to absorb a noised image at a selected time step and return the anticipated noise. Note that the anticipated noise is a tensor that has the identical size/resolution because the input image. So technically, the network takes in and outputs tensors of the identical shape. What sort of neural network can we use for this?

What is often used here could be very just like that of an Autoencoder, which you might remember from typical “intro to deep learning” tutorials. Autoencoders have a so-called “bottleneck” layer in between the encoder and decoder. The encoder first encodes a picture right into a smaller hidden representation called the “bottleneck”, and the decoder then decodes that hidden representation back into an actual image. This forces the network to only keep crucial information within the bottleneck layer.

By way of architecture, the DDPM authors went for a U-Net, introduced by (Ronneberger et al., 2015) (which, on the time, achieved state-of-the-art results for medical image segmentation). This network, like every autoencoder, consists of a bottleneck in the center that makes sure the network learns only crucial information. Importantly, it introduced residual connections between the encoder and decoder, greatly improving gradient flow (inspired by ResNet in He et al., 2015).

As will be seen, a U-Net model first downsamples the input (i.e. makes the input smaller by way of spatial resolution), after which upsampling is performed.

Below, we implement this network, step-by-step.

Network helpers

First, we define some helper functions and classes which shall be used when implementing the neural network. Importantly, we define a Residual module, which simply adds the input to the output of a selected function (in other words, adds a residual connection to a selected function).

We also define aliases for the up- and downsampling operations.

def exists(x):

return x is not None

def default(val, d):

if exists(val):

return val

return d() if isfunction(d) else d

def num_to_groups(num, divisor):

groups = num // divisor

remainder = num % divisor

arr = [divisor] * groups

if remainder > 0:

arr.append(remainder)

return arr

class Residual(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, fn):

super().__init__()

self.fn = fn

def forward(self, x, *args, **kwargs):

return self.fn(x, *args, **kwargs) + x

def Upsample(dim, dim_out=None):

return nn.Sequential(

nn.Upsample(scale_factor=2, mode="nearest"),

nn.Conv2d(dim, default(dim_out, dim), 3, padding=1),

)

def Downsample(dim, dim_out=None):

return nn.Sequential(

Rearrange("b c (h p1) (w p2) -> b (c p1 p2) h w", p1=2, p2=2),

nn.Conv2d(dim * 4, default(dim_out, dim), 1),

)

Position embeddings

Because the parameters of the neural network are shared across time (noise level), the authors employ sinusoidal position embeddings to encode , inspired by the Transformer (Vaswani et al., 2017). This makes the neural network “know” at which particular time step (noise level) it is working, for each image in a batch.

The SinusoidalPositionEmbeddings module takes a tensor of shape (batch_size, 1) as input (i.e. the noise levels of several noisy images in a batch), and turns this right into a tensor of shape (batch_size, dim), with dim being the dimensionality of the position embeddings. That is then added to every residual block, as we are going to see further.

class SinusoidalPositionEmbeddings(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, dim):

super().__init__()

self.dim = dim

def forward(self, time):

device = time.device

half_dim = self.dim // 2

embeddings = math.log(10000) / (half_dim - 1)

embeddings = torch.exp(torch.arange(half_dim, device=device) * -embeddings)

embeddings = time[:, None] * embeddings[None, :]

embeddings = torch.cat((embeddings.sin(), embeddings.cos()), dim=-1)

return embeddings

ResNet block

Next, we define the core constructing block of the U-Net model. The DDPM authors employed a Wide ResNet block (Zagoruyko et al., 2016), but Phil Wang has replaced the usual convolutional layer by a “weight standardized” version, which works higher together with group normalization (see (Kolesnikov et al., 2019) for details).

class WeightStandardizedConv2d(nn.Conv2d):

"""

https://arxiv.org/abs/1903.10520

weight standardization purportedly works synergistically with group normalization

"""

def forward(self, x):

eps = 1e-5 if x.dtype == torch.float32 else 1e-3

weight = self.weight

mean = reduce(weight, "o ... -> o 1 1 1", "mean")

var = reduce(weight, "o ... -> o 1 1 1", partial(torch.var, unbiased=False))

normalized_weight = (weight - mean) * (var + eps).rsqrt()

return F.conv2d(

x,

normalized_weight,

self.bias,

self.stride,

self.padding,

self.dilation,

self.groups,

)

class Block(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, dim, dim_out, groups=8):

super().__init__()

self.proj = WeightStandardizedConv2d(dim, dim_out, 3, padding=1)

self.norm = nn.GroupNorm(groups, dim_out)

self.act = nn.SiLU()

def forward(self, x, scale_shift=None):

x = self.proj(x)

x = self.norm(x)

if exists(scale_shift):

scale, shift = scale_shift

x = x * (scale + 1) + shift

x = self.act(x)

return x

class ResnetBlock(nn.Module):

"""https://arxiv.org/abs/1512.03385"""

def __init__(self, dim, dim_out, *, time_emb_dim=None, groups=8):

super().__init__()

self.mlp = (

nn.Sequential(nn.SiLU(), nn.Linear(time_emb_dim, dim_out * 2))

if exists(time_emb_dim)

else None

)

self.block1 = Block(dim, dim_out, groups=groups)

self.block2 = Block(dim_out, dim_out, groups=groups)

self.res_conv = nn.Conv2d(dim, dim_out, 1) if dim != dim_out else nn.Identity()

def forward(self, x, time_emb=None):

scale_shift = None

if exists(self.mlp) and exists(time_emb):

time_emb = self.mlp(time_emb)

time_emb = rearrange(time_emb, "b c -> b c 1 1")

scale_shift = time_emb.chunk(2, dim=1)

h = self.block1(x, scale_shift=scale_shift)

h = self.block2(h)

return h + self.res_conv(x)

Attention module

Next, we define the eye module, which the DDPM authors added in between the convolutional blocks. Attention is the constructing block of the famous Transformer architecture (Vaswani et al., 2017), which has shown great success in various domains of AI, from NLP and vision to protein folding. Phil Wang employs 2 variants of attention: one is regular multi-head self-attention (as utilized in the Transformer), the opposite one is a linear attention variant (Shen et al., 2018), whose time- and memory requirements scale linear within the sequence length, versus quadratic for normal attention.

For an intensive explanation of the eye mechanism, we refer the reader to Jay Allamar’s wonderful blog post.

class Attention(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, dim, heads=4, dim_head=32):

super().__init__()

self.scale = dim_head**-0.5

self.heads = heads

hidden_dim = dim_head * heads

self.to_qkv = nn.Conv2d(dim, hidden_dim * 3, 1, bias=False)

self.to_out = nn.Conv2d(hidden_dim, dim, 1)

def forward(self, x):

b, c, h, w = x.shape

qkv = self.to_qkv(x).chunk(3, dim=1)

q, k, v = map(

lambda t: rearrange(t, "b (h c) x y -> b h c (x y)", h=self.heads), qkv

)

q = q * self.scale

sim = einsum("b h d i, b h d j -> b h i j", q, k)

sim = sim - sim.amax(dim=-1, keepdim=True).detach()

attn = sim.softmax(dim=-1)

out = einsum("b h i j, b h d j -> b h i d", attn, v)

out = rearrange(out, "b h (x y) d -> b (h d) x y", x=h, y=w)

return self.to_out(out)

class LinearAttention(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, dim, heads=4, dim_head=32):

super().__init__()

self.scale = dim_head**-0.5

self.heads = heads

hidden_dim = dim_head * heads

self.to_qkv = nn.Conv2d(dim, hidden_dim * 3, 1, bias=False)

self.to_out = nn.Sequential(nn.Conv2d(hidden_dim, dim, 1),

nn.GroupNorm(1, dim))

def forward(self, x):

b, c, h, w = x.shape

qkv = self.to_qkv(x).chunk(3, dim=1)

q, k, v = map(

lambda t: rearrange(t, "b (h c) x y -> b h c (x y)", h=self.heads), qkv

)

q = q.softmax(dim=-2)

k = k.softmax(dim=-1)

q = q * self.scale

context = torch.einsum("b h d n, b h e n -> b h d e", k, v)

out = torch.einsum("b h d e, b h d n -> b h e n", context, q)

out = rearrange(out, "b h c (x y) -> b (h c) x y", h=self.heads, x=h, y=w)

return self.to_out(out)

Group normalization

The DDPM authors interleave the convolutional/attention layers of the U-Net with group normalization (Wu et al., 2018). Below, we define a PreNorm class, which shall be used to use groupnorm before the eye layer, as we’ll see further. Note that there is been a debate about whether to use normalization before or after attention in Transformers.

class PreNorm(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, dim, fn):

super().__init__()

self.fn = fn

self.norm = nn.GroupNorm(1, dim)

def forward(self, x):

x = self.norm(x)

return self.fn(x)

Conditional U-Net

Now that we have defined all constructing blocks (position embeddings, ResNet blocks, attention and group normalization), it is time to define your entire neural network. Recall that the job of the network is to absorb a batch of noisy images and their respective noise levels, and output the noise added to the input. More formally:

- the network takes a batch of noisy images of shape

(batch_size, num_channels, height, width)and a batch of noise levels of shape(batch_size, 1)as input, and returns a tensor of shape(batch_size, num_channels, height, width)

The network is built up as follows:

- first, a convolutional layer is applied on the batch of noisy images, and position embeddings are computed for the noise levels

- next, a sequence of downsampling stages are applied. Each downsampling stage consists of two ResNet blocks + groupnorm + attention + residual connection + a downsample operation

- at the center of the network, again ResNet blocks are applied, interleaved with attention

- next, a sequence of upsampling stages are applied. Each upsampling stage consists of two ResNet blocks + groupnorm + attention + residual connection + an upsample operation

- finally, a ResNet block followed by a convolutional layer is applied.

Ultimately, neural networks stack up layers as in the event that they were lego blocks (but it surely’s essential to understand how they work).

class Unet(nn.Module):

def __init__(

self,

dim,

init_dim=None,

out_dim=None,

dim_mults=(1, 2, 4, 8),

channels=3,

self_condition=False,

resnet_block_groups=4,

):

super().__init__()

self.channels = channels

self.self_condition = self_condition

input_channels = channels * (2 if self_condition else 1)

init_dim = default(init_dim, dim)

self.init_conv = nn.Conv2d(input_channels, init_dim, 1, padding=0)

dims = [init_dim, *map(lambda m: dim * m, dim_mults)]

in_out = list(zip(dims[:-1], dims[1:]))

block_klass = partial(ResnetBlock, groups=resnet_block_groups)

time_dim = dim * 4

self.time_mlp = nn.Sequential(

SinusoidalPositionEmbeddings(dim),

nn.Linear(dim, time_dim),

nn.GELU(),

nn.Linear(time_dim, time_dim),

)

self.downs = nn.ModuleList([])

self.ups = nn.ModuleList([])

num_resolutions = len(in_out)

for ind, (dim_in, dim_out) in enumerate(in_out):

is_last = ind >= (num_resolutions - 1)

self.downs.append(

nn.ModuleList(

[

block_klass(dim_in, dim_in, time_emb_dim=time_dim),

block_klass(dim_in, dim_in, time_emb_dim=time_dim),

Residual(PreNorm(dim_in, LinearAttention(dim_in))),

Downsample(dim_in, dim_out)

if not is_last

else nn.Conv2d(dim_in, dim_out, 3, padding=1),

]

)

)

mid_dim = dims[-1]

self.mid_block1 = block_klass(mid_dim, mid_dim, time_emb_dim=time_dim)

self.mid_attn = Residual(PreNorm(mid_dim, Attention(mid_dim)))

self.mid_block2 = block_klass(mid_dim, mid_dim, time_emb_dim=time_dim)

for ind, (dim_in, dim_out) in enumerate(reversed(in_out)):

is_last = ind == (len(in_out) - 1)

self.ups.append(

nn.ModuleList(

[

block_klass(dim_out + dim_in, dim_out, time_emb_dim=time_dim),

block_klass(dim_out + dim_in, dim_out, time_emb_dim=time_dim),

Residual(PreNorm(dim_out, LinearAttention(dim_out))),

Upsample(dim_out, dim_in)

if not is_last

else nn.Conv2d(dim_out, dim_in, 3, padding=1),

]

)

)

self.out_dim = default(out_dim, channels)

self.final_res_block = block_klass(dim * 2, dim, time_emb_dim=time_dim)

self.final_conv = nn.Conv2d(dim, self.out_dim, 1)

def forward(self, x, time, x_self_cond=None):

if self.self_condition:

x_self_cond = default(x_self_cond, lambda: torch.zeros_like(x))

x = torch.cat((x_self_cond, x), dim=1)

x = self.init_conv(x)

r = x.clone()

t = self.time_mlp(time)

h = []

for block1, block2, attn, downsample in self.downs:

x = block1(x, t)

h.append(x)

x = block2(x, t)

x = attn(x)

h.append(x)

x = downsample(x)

x = self.mid_block1(x, t)

x = self.mid_attn(x)

x = self.mid_block2(x, t)

for block1, block2, attn, upsample in self.ups:

x = torch.cat((x, h.pop()), dim=1)

x = block1(x, t)

x = torch.cat((x, h.pop()), dim=1)

x = block2(x, t)

x = attn(x)

x = upsample(x)

x = torch.cat((x, r), dim=1)

x = self.final_res_block(x, t)

return self.final_conv(x)

Defining the forward diffusion process

The forward diffusion process progressively adds noise to a picture from the true distribution, in plenty of time steps . This happens in response to a variance schedule. The unique DDPM authors employed a linear schedule:

We set the forward process variances to constants

increasing linearly from

to .

Nevertheless, it was shown in (Nichol et al., 2021) that higher results will be achieved when employing a cosine schedule.

Below, we define various schedules for the timesteps (we’ll select one afterward).

def cosine_beta_schedule(timesteps, s=0.008):

"""

cosine schedule as proposed in https://arxiv.org/abs/2102.09672

"""

steps = timesteps + 1

x = torch.linspace(0, timesteps, steps)

alphas_cumprod = torch.cos(((x / timesteps) + s) / (1 + s) * torch.pi * 0.5) ** 2

alphas_cumprod = alphas_cumprod / alphas_cumprod[0]

betas = 1 - (alphas_cumprod[1:] / alphas_cumprod[:-1])

return torch.clip(betas, 0.0001, 0.9999)

def linear_beta_schedule(timesteps):

beta_start = 0.0001

beta_end = 0.02

return torch.linspace(beta_start, beta_end, timesteps)

def quadratic_beta_schedule(timesteps):

beta_start = 0.0001

beta_end = 0.02

return torch.linspace(beta_start**0.5, beta_end**0.5, timesteps) ** 2

def sigmoid_beta_schedule(timesteps):

beta_start = 0.0001

beta_end = 0.02

betas = torch.linspace(-6, 6, timesteps)

return torch.sigmoid(betas) * (beta_end - beta_start) + beta_start

To start out with, let’s use the linear schedule for time steps and define the varied variables from the which we are going to need, similar to the cumulative product of the variances . Each of the variables below are only 1-dimensional tensors, storing values from to . Importantly, we also define an extract function, which can allow us to extract the suitable index for a batch of indices.

timesteps = 300

betas = linear_beta_schedule(timesteps=timesteps)

alphas = 1. - betas

alphas_cumprod = torch.cumprod(alphas, axis=0)

alphas_cumprod_prev = F.pad(alphas_cumprod[:-1], (1, 0), value=1.0)

sqrt_recip_alphas = torch.sqrt(1.0 / alphas)

sqrt_alphas_cumprod = torch.sqrt(alphas_cumprod)

sqrt_one_minus_alphas_cumprod = torch.sqrt(1. - alphas_cumprod)

posterior_variance = betas * (1. - alphas_cumprod_prev) / (1. - alphas_cumprod)

def extract(a, t, x_shape):

batch_size = t.shape[0]

out = a.gather(-1, t.cpu())

return out.reshape(batch_size, *((1,) * (len(x_shape) - 1))).to(t.device)

We’ll illustrate with a cats image how noise is added at every time step of the diffusion process.

from PIL import Image

import requests

url = 'http://images.cocodataset.org/val2017/000000039769.jpg'

image = Image.open(requests.get(url, stream=True).raw)

image

Noise is added to PyTorch tensors, reasonably than Pillow Images. We’ll first define image transformations that allow us to go from a PIL image to a PyTorch tensor (on which we are able to add the noise), and vice versa.

These transformations are fairly easy: we first normalize images by dividing by (such that they’re within the range), after which make certain they’re within the range. From the DPPM paper:

We assume that image data consists of integers in scaled linearly to . This

ensures that the neural network reverse process operates on consistently scaled inputs ranging from

the usual normal prior .

from torchvision.transforms import Compose, ToTensor, Lambda, ToPILImage, CenterCrop, Resize

image_size = 128

transform = Compose([

Resize(image_size),

CenterCrop(image_size),

ToTensor(),

Lambda(lambda t: (t * 2) - 1),

])

x_start = transform(image).unsqueeze(0)

x_start.shape

Output:

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

torch.Size([1, 3, 128, 128])

We also define the reverse transform, which takes in a PyTorch tensor containing values in and switch them back right into a PIL image:

import numpy as np

reverse_transform = Compose([

Lambda(lambda t: (t + 1) / 2),

Lambda(lambda t: t.permute(1, 2, 0)),

Lambda(lambda t: t * 255.),

Lambda(lambda t: t.numpy().astype(np.uint8)),

ToPILImage(),

])

Let’s confirm this:

reverse_transform(x_start.squeeze())

We are able to now define the forward diffusion process as within the paper:

def q_sample(x_start, t, noise=None):

if noise is None:

noise = torch.randn_like(x_start)

sqrt_alphas_cumprod_t = extract(sqrt_alphas_cumprod, t, x_start.shape)

sqrt_one_minus_alphas_cumprod_t = extract(

sqrt_one_minus_alphas_cumprod, t, x_start.shape

)

return sqrt_alphas_cumprod_t * x_start + sqrt_one_minus_alphas_cumprod_t * noise

Let’s test it on a selected time step:

def get_noisy_image(x_start, t):

x_noisy = q_sample(x_start, t=t)

noisy_image = reverse_transform(x_noisy.squeeze())

return noisy_image

t = torch.tensor([40])

get_noisy_image(x_start, t)

Let’s visualize this for various time steps:

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

torch.manual_seed(0)

def plot(imgs, with_orig=False, row_title=None, **imshow_kwargs):

if not isinstance(imgs[0], list):

imgs = [imgs]

num_rows = len(imgs)

num_cols = len(imgs[0]) + with_orig

fig, axs = plt.subplots(figsize=(200,200), nrows=num_rows, ncols=num_cols, squeeze=False)

for row_idx, row in enumerate(imgs):

row = [image] + row if with_orig else row

for col_idx, img in enumerate(row):

ax = axs[row_idx, col_idx]

ax.imshow(np.asarray(img), **imshow_kwargs)

ax.set(xticklabels=[], yticklabels=[], xticks=[], yticks=[])

if with_orig:

axs[0, 0].set(title='Original image')

axs[0, 0].title.set_size(8)

if row_title is not None:

for row_idx in range(num_rows):

axs[row_idx, 0].set(ylabel=row_title[row_idx])

plt.tight_layout()

plot([get_noisy_image(x_start, torch.tensor([t])) for t in [0, 50, 100, 150, 199]])

Which means that we are able to now define the loss function given the model as follows:

def p_losses(denoise_model, x_start, t, noise=None, loss_type="l1"):

if noise is None:

noise = torch.randn_like(x_start)

x_noisy = q_sample(x_start=x_start, t=t, noise=noise)

predicted_noise = denoise_model(x_noisy, t)

if loss_type == 'l1':

loss = F.l1_loss(noise, predicted_noise)

elif loss_type == 'l2':

loss = F.mse_loss(noise, predicted_noise)

elif loss_type == "huber":

loss = F.smooth_l1_loss(noise, predicted_noise)

else:

raise NotImplementedError()

return loss

The denoise_model shall be our U-Net defined above. We’ll employ the Huber loss between the true and the anticipated noise.

Define a PyTorch Dataset + DataLoader

Here we define a daily PyTorch Dataset. The dataset simply consists of images from an actual dataset, like Fashion-MNIST, CIFAR-10 or ImageNet, scaled linearly to .

Each image is resized to the identical size. Interesting to notice is that images are also randomly horizontally flipped. From the paper:

We used random horizontal flips during training for CIFAR10; we tried training each with and without flips, and located flips to enhance sample quality barely.

Here we use the 🤗 Datasets library to simply load the Fashion MNIST dataset from the hub. This dataset consists of images which have already got the identical resolution, namely 28×28.

from datasets import load_dataset

dataset = load_dataset("fashion_mnist")

image_size = 28

channels = 1

batch_size = 128

Next, we define a function which we’ll apply on-the-fly on your entire dataset. We use the with_transform functionality for that. The function just applies some basic image preprocessing: random horizontal flips, rescaling and at last make them have values within the range.

from torchvision import transforms

from torch.utils.data import DataLoader

transform = Compose([

transforms.RandomHorizontalFlip(),

transforms.ToTensor(),

transforms.Lambda(lambda t: (t * 2) - 1)

])

def transforms(examples):

examples["pixel_values"] = [transform(image.convert("L")) for image in examples["image"]]

del examples["image"]

return examples

transformed_dataset = dataset.with_transform(transforms).remove_columns("label")

dataloader = DataLoader(transformed_dataset["train"], batch_size=batch_size, shuffle=True)

batch = next(iter(dataloader))

print(batch.keys())

Output:

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

dict_keys(['pixel_values'])

Sampling

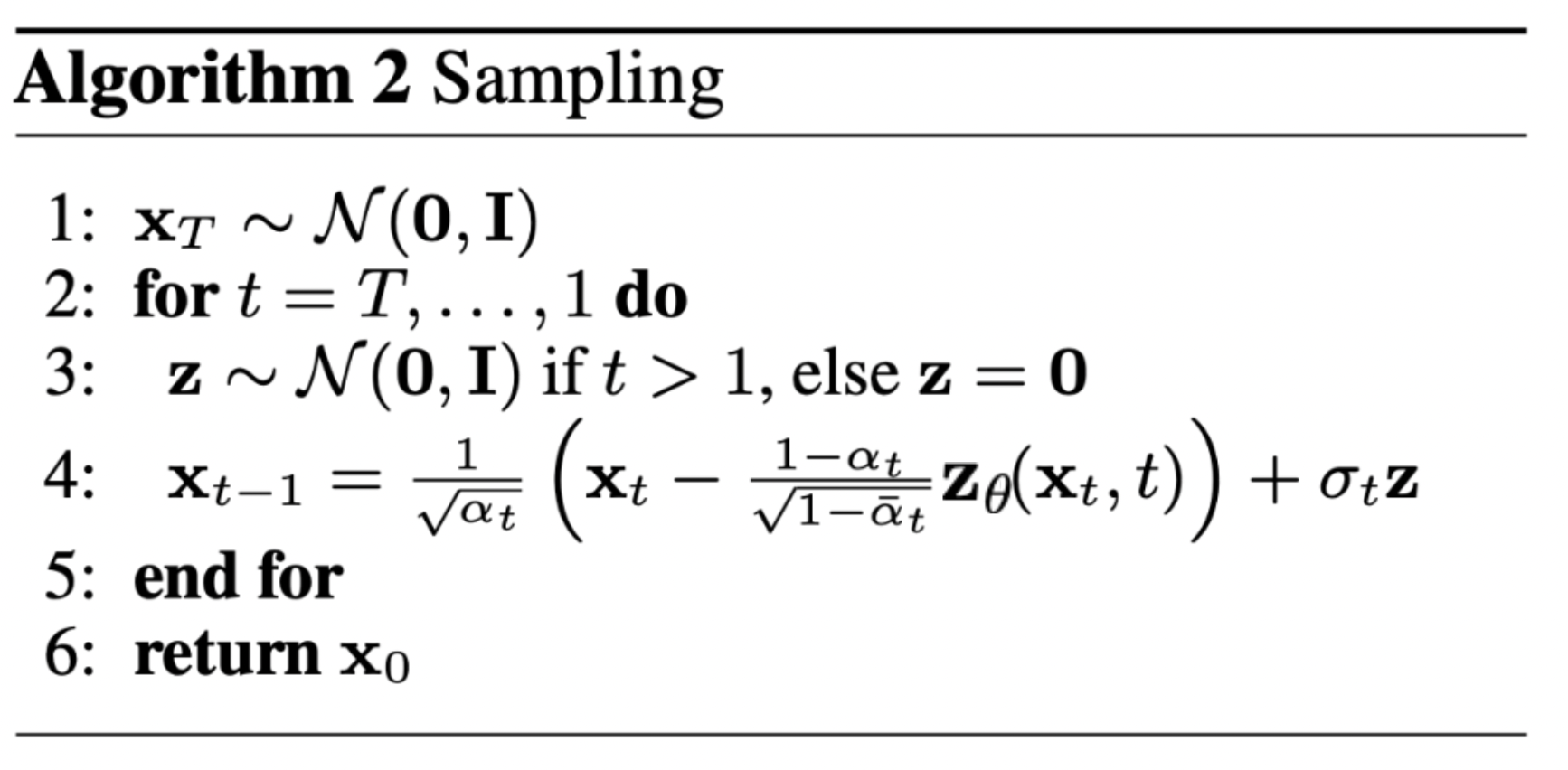

As we’ll sample from the model during training (to be able to track progress), we define the code for that below. Sampling is summarized within the paper as Algorithm 2:

Generating latest images from a diffusion model happens by reversing the diffusion process: we start from , where we sample pure noise from a Gaussian distribution, after which use our neural network to progressively denoise it (using the conditional probability it has learned), until we find yourself at time step . As shown above, we are able to derive a slighly less denoised image by plugging within the reparametrization of the mean, using our noise predictor. Do not forget that the variance is thought ahead of time.

Ideally, we find yourself with a picture that appears prefer it got here from the true data distribution.

The code below implements this.

@torch.no_grad()

def p_sample(model, x, t, t_index):

betas_t = extract(betas, t, x.shape)

sqrt_one_minus_alphas_cumprod_t = extract(

sqrt_one_minus_alphas_cumprod, t, x.shape

)

sqrt_recip_alphas_t = extract(sqrt_recip_alphas, t, x.shape)

model_mean = sqrt_recip_alphas_t * (

x - betas_t * model(x, t) / sqrt_one_minus_alphas_cumprod_t

)

if t_index == 0:

return model_mean

else:

posterior_variance_t = extract(posterior_variance, t, x.shape)

noise = torch.randn_like(x)

return model_mean + torch.sqrt(posterior_variance_t) * noise

@torch.no_grad()

def p_sample_loop(model, shape):

device = next(model.parameters()).device

b = shape[0]

img = torch.randn(shape, device=device)

imgs = []

for i in tqdm(reversed(range(0, timesteps)), desc='sampling loop time step', total=timesteps):

img = p_sample(model, img, torch.full((b,), i, device=device, dtype=torch.long), i)

imgs.append(img.cpu().numpy())

return imgs

@torch.no_grad()

def sample(model, image_size, batch_size=16, channels=3):

return p_sample_loop(model, shape=(batch_size, channels, image_size, image_size))

Note that the code above is a simplified version of the unique implementation. We found our simplification (which is consistent with Algorithm 2 within the paper) to work just in addition to the original, more complex implementation, which employs clipping.

Train the model

Next, we train the model in regular PyTorch fashion. We also define some logic to periodically save generated images, using the sample method defined above.

from pathlib import Path

def num_to_groups(num, divisor):

groups = num // divisor

remainder = num % divisor

arr = [divisor] * groups

if remainder > 0:

arr.append(remainder)

return arr

results_folder = Path("./results")

results_folder.mkdir(exist_ok = True)

save_and_sample_every = 1000

Below, we define the model, and move it to the GPU. We also define a regular optimizer (Adam).

from torch.optim import Adam

device = "cuda" if torch.cuda.is_available() else "cpu"

model = Unet(

dim=image_size,

channels=channels,

dim_mults=(1, 2, 4,)

)

model.to(device)

optimizer = Adam(model.parameters(), lr=1e-3)

Let’s start training!

from torchvision.utils import save_image

epochs = 6

for epoch in range(epochs):

for step, batch in enumerate(dataloader):

optimizer.zero_grad()

batch_size = batch["pixel_values"].shape[0]

batch = batch["pixel_values"].to(device)

t = torch.randint(0, timesteps, (batch_size,), device=device).long()

loss = p_losses(model, batch, t, loss_type="huber")

if step % 100 == 0:

print("Loss:", loss.item())

loss.backward()

optimizer.step()

if step != 0 and step % save_and_sample_every == 0:

milestone = step // save_and_sample_every

batches = num_to_groups(4, batch_size)

all_images_list = list(map(lambda n: sample(model, batch_size=n, channels=channels), batches))

all_images = torch.cat(all_images_list, dim=0)

all_images = (all_images + 1) * 0.5

save_image(all_images, str(results_folder / f'sample-{milestone}.png'), nrow = 6)

Output:

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Loss: 0.46477368474006653

Loss: 0.12143351882696152

Loss: 0.08106148988008499

Loss: 0.0801810547709465

Loss: 0.06122320517897606

Loss: 0.06310459971427917

Loss: 0.05681884288787842

Loss: 0.05729678273200989

Loss: 0.05497899278998375

Loss: 0.04439849033951759

Loss: 0.05415581166744232

Loss: 0.06020551547408104

Loss: 0.046830907464027405

Loss: 0.051029372960329056

Loss: 0.0478244312107563

Loss: 0.046767622232437134

Loss: 0.04305662214756012

Loss: 0.05216279625892639

Loss: 0.04748568311333656

Loss: 0.05107741802930832

Loss: 0.04588869959115982

Loss: 0.043014321476221085

Loss: 0.046371955424547195

Loss: 0.04952816292643547

Loss: 0.04472338408231735

Sampling (inference)

To sample from the model, we are able to just use our sample function defined above:

samples = sample(model, image_size=image_size, batch_size=64, channels=channels)

random_index = 5

plt.imshow(samples[-1][random_index].reshape(image_size, image_size, channels), cmap="gray")

Looks as if the model is able to generating a pleasant T-shirt! Take into accout that the dataset we trained on is pretty low-resolution (28×28).

We can even create a gif of the denoising process:

import matplotlib.animation as animation

random_index = 53

fig = plt.figure()

ims = []

for i in range(timesteps):

im = plt.imshow(samples[i][random_index].reshape(image_size, image_size, channels), cmap="gray", animated=True)

ims.append([im])

animate = animation.ArtistAnimation(fig, ims, interval=50, blit=True, repeat_delay=1000)

animate.save('diffusion.gif')

plt.show()

Follow-up reads

Note that the DDPM paper showed that diffusion models are a promising direction for (un)conditional image generation. This has since then (immensely) been improved, most notably for text-conditional image generation. Below, we list some essential (but removed from exhaustive) follow-up works:

- Improved Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Models (Nichol et al., 2021): finds that learning the variance of the conditional distribution (besides the mean) helps in improving performance

- Cascaded Diffusion Models for High Fidelity Image Generation (Ho et al., 2021): introduces cascaded diffusion, which comprises a pipeline of multiple diffusion models that generate images of accelerating resolution for high-fidelity image synthesis

- Diffusion Models Beat GANs on Image Synthesis (Dhariwal et al., 2021): show that diffusion models can achieve image sample quality superior to the present state-of-the-art generative models by improving the U-Net architecture, in addition to introducing classifier guidance

- Classifier-Free Diffusion Guidance (Ho et al., 2021): shows that you just don’t need a classifier for guiding a diffusion model by jointly training a conditional and an unconditional diffusion model with a single neural network

- Hierarchical Text-Conditional Image Generation with CLIP Latents (DALL-E 2) (Ramesh et al., 2022): uses a previous to show a text caption right into a CLIP image embedding, after which a diffusion model decodes it into a picture

- Photorealistic Text-to-Image Diffusion Models with Deep Language Understanding (ImageGen) (Saharia et al., 2022): shows that combining a big pre-trained language model (e.g. T5) with cascaded diffusion works well for text-to-image synthesis

Note that this list only includes essential works until the time of writing, which is June seventh, 2022.

For now, it appears that evidently the principal (perhaps only) drawback of diffusion models is that they require multiple forward passes to generate a picture (which shouldn’t be the case for generative models like GANs). Nevertheless, there’s research happening that allows high-fidelity generation in as few as 10 denoising steps.