I even have two audiences in mind while writing this. One is biologists who are attempting to get into machine learning, and the opposite is machine learners who are attempting to get into biology. When you’re not conversant in either biology or machine learning then you definately’re still welcome to come back along, but you may find it a bit confusing at times! And for those who’re already conversant in each, then you definately probably don’t need this post in any respect – you possibly can just skip straight to our example notebooks to see these models in motion:

- Wonderful-tuning protein language models (PyTorch, TensorFlow)

- Protein folding with ESMFold (PyTorch just for now due to

openfolddependencies)

Introduction for biologists: What the hell is a language model?

The models used to handle proteins are heavily inspired by large language models like BERT and GPT. So to grasp how these models work we’re going to return in time to 2016 or so, before they existed. Donald Trump hasn’t been elected yet, Brexit hasn’t yet happened, and Deep Learning (DL) is the new latest technique that’s breaking latest records day by day. The important thing to DL’s success is that it uses artificial neural networks to learn complex patterns in data. DL has one critical problem, though – it needs a lot of knowledge to work well, and on many tasks that data just isn’t available.

Let’s say that you should train a DL model to take a sentence in English as input and choose if it’s grammatically correct or not. So that you assemble your training data, and it looks something like this:

| Text | Label |

|---|---|

| The judge told the jurors to think twice. | Correct |

| The judge told that the jurors to think twice. | Incorrect |

| … | … |

In theory, this task was completely possible on the time – for those who fed training data like this right into a DL model, it could learn to predict whether latest sentences were grammatically correct or not. In practice, it didn’t work so well, because in 2016 most individuals randomly initialized a brand new model for every task they desired to train them on. This meant that models needed to learn every part they needed to know just from the examples within the training data!

To grasp just how difficult that’s, pretend you’re a machine learning model and I’m supplying you with some training data for a task I need you to learn. Here it’s:

| Text | Label |

|---|---|

| Is í an stiúrthóir is fearr ar domhan! | 1 |

| Is fuath liom an scannán search engine marketing. | 0 |

| Scannán den scoth ab ea é. | 1 |

| D’fhág mé an phictiúrlann tar éis fiche nóiméad! | 0 |

I selected a language here that I’m hoping you’ve never seen before, and so I’m guessing you almost certainly don’t feel very confident that you just’ve learned this task. Possibly after a whole lot or 1000’s of examples you may begin to notice some recurring words or patterns within the inputs, and you may have the opportunity to make guesses that were higher than random probability, but even then a brand new word or unusual phrasing would definitely have the opportunity to throw you and make you guess incorrectly. Not coincidentally, that’s about how well DL models performed on the time too!

Now try the identical task, but in English:

| Text | Label |

|---|---|

| She’s the perfect director on this planet! | 1 |

| I hate this movie. | 0 |

| It was a fully excellent film. | 1 |

| I left the cinema after twenty minutes! | 0 |

Now it’s easy – the duty is just predicting whether a movie review is positive (1) or negative (0). With just two positive examples and two negative examples, you could possibly probably do that task with near 100% accuracy, because you have already got an enormous pre-existing knowledge of English vocabulary and grammar, in addition to cultural context surrounding movies and emotional expression. Without that knowledge, things are more just like the first task – you would wish to read an enormous variety of examples before you start to identify even superficial patterns within the inputs, and even for those who took the time to check a whole lot of 1000’s of examples your guesses would still be far less accurate than they’re after only 4 examples within the English language task.

The critical breakthrough: Transfer learning

In machine learning, we call this idea of transferring prior knowledge to a brand new task “transfer learning”. Getting this sort of transfer learning to work for DL was a significant goal for the sector around 2016. Things like pre-trained word vectors (that are very interesting, but outside the scope of this blogpost!) did exist by 2016 and allowed some knowledge to be transferred to latest models, but this information transfer was still relatively superficial, and models still needed large amounts of coaching data to work well.

This stage of affairs continued until 2018, when two huge papers landed, introducing the models ULMFiT and later BERT. These were the primary papers that got transfer learning in natural language to work rather well, and BERT specifically marked the start of the era of pre-trained large language models. The trick, shared by each papers, is that they took advantage of the interior structure of the substitute neural networks in deep learning – they trained a neural net for a very long time on a text task where training data was very abundant, after which they simply copied the entire neural network to a brand new task, changing only the few neurons that corresponded to the network’s output.

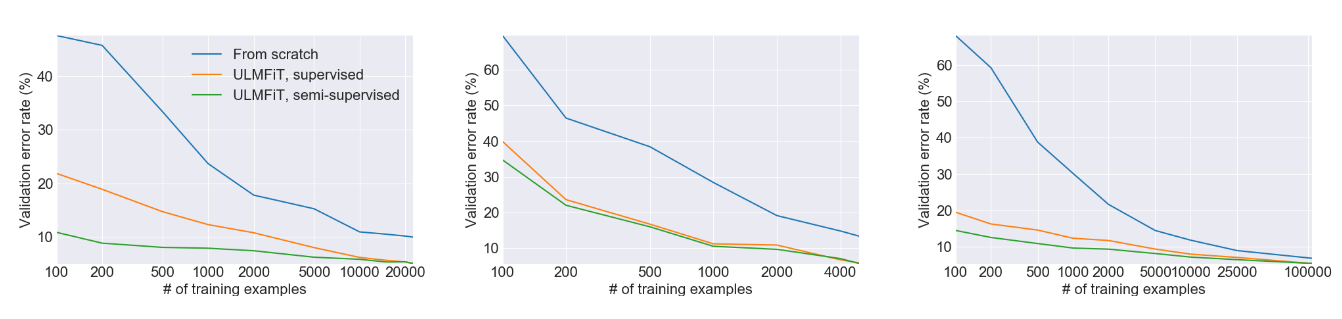

This figure from the ULMFiT paper shows the big gains in performance from using transfer learning versus training a model from scratch on three separate tasks. In lots of cases, using transfer learning yields performance such as having greater than 100X as much training data. And don’t forget that this was published in 2018 – modern large language models can do even higher!

The rationale this works is that within the means of solving any non-trivial task, neural networks learn plenty of the structure of the input data – visual networks, given raw pixels, learn to discover lines and curves and edges; text networks, given raw text, learn details of grammatical structure. This information shouldn’t be task-specific, nevertheless – the important thing reason transfer learning works is that plenty of what you’ll want to know to resolve a task shouldn’t be specific to that task! To categorise movie reviews you didn’t must know lots about movie reviews, but you probably did need an enormous knowledge of English and cultural context. By picking a task where training data is abundant, we are able to get a neural network to learn that form of “domain knowledge” after which later apply it to latest tasks we care about, where training data is perhaps lots harder to come back by.

At this point, hopefully you understand what transfer learning is, and that a big language model is just an enormous neural network that’s been trained on plenty of text data, which makes it a main candidate for transferring to latest tasks. We’ll see how these same techniques may be applied to proteins below, but first I would like to put in writing an introduction for the opposite half of my audience. Be happy to skip this next bit for those who’re already familiar!

Introduction for machine learning people: What the hell is a protein?

To condense a whole degree into one sentence: Proteins do plenty of stuff. Some proteins are enzymes – they act as catalysts for chemical reactions. When your body converts nutrients to energy, each step of the trail from food to muscle movement is catalyzed by an enzyme. Some proteins are structural – they offer stability and shape, for instance in connective tissue. When you’ve ever seen a cosmetics commercial you’ve probably seen words like collagen and elastin and keratin – these are proteins that form plenty of the structure of our skin and hair.

Other proteins are critical in health and disease – everyone probably remembers infinite news reports on the spike protein of the COVID-19 virus. The COVID spike protein binds to a protein called ACE2 that’s found on the surface of human cells, which allows it to enter the cell and deliver its payload of viral RNA. Because this interaction was so critical to infection, modelling these proteins and their interactions was an enormous focus in the course of the pandemic.

Proteins are composed of multiple amino acids. Amino acids are relatively easy molecules that every one share the identical molecular backbone, and the chemistry of this backbone allows amino acids to fuse together, in order that the person molecules can turn into an extended chain. The critical thing to grasp here is that there are only just a few different amino acids – 20 standard ones, plus possibly a few rare and bizarre ones depending on the particular organism in query. What gives rise to the large diversity of proteins is that these amino acids may be combined in any order, and the resulting protein chain can have vastly different shapes and functions consequently, as different parts of the chain stick and fold onto one another. Consider text as an analogy here – English only has 26 letters, and yet consider all the various sorts of things you possibly can write with combos of those 26 letters!

In truth, because there are so few amino acids, biologists can assign a singular letter of the alphabet to each. This implies which you could write a protein just as a text string! For instance, let’s say a protein has the amino acids Methionine, Alanine and Histidine in a sequence. The corresponding letters for those amino acids are only M, A and H, and so we could write that chain as just “MAH”. Most proteins contain a whole lot and even 1000’s of amino acids somewhat than simply three, though!

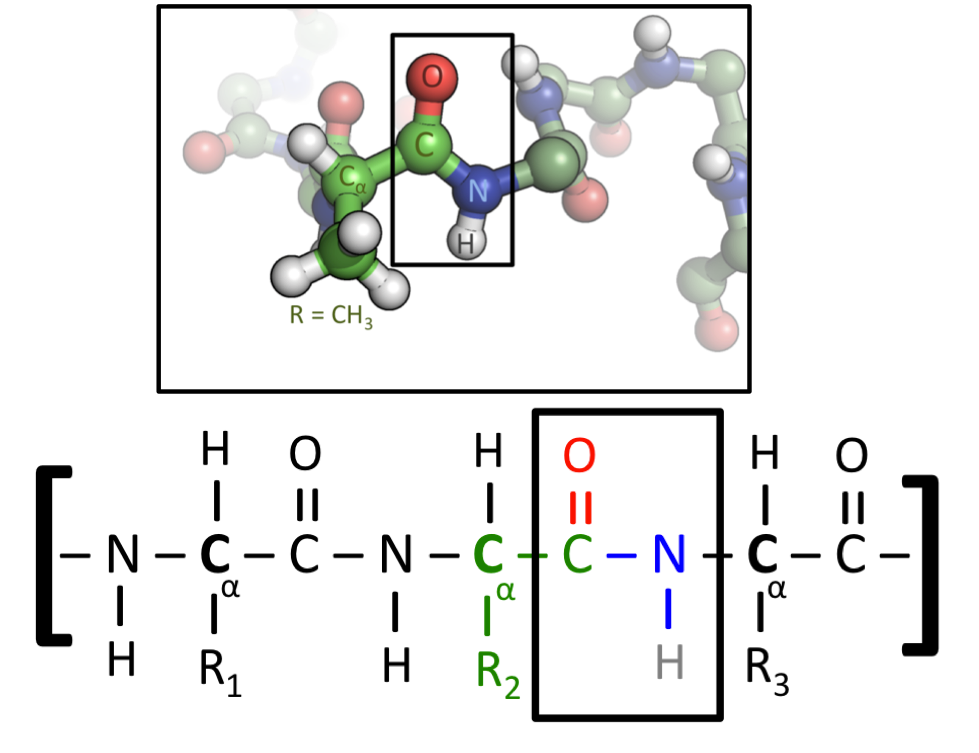

This figure shows two representations of a protein. All amino acids contain a Carbon-Carbon-Nitrogen sequence. When amino acids are fused right into a protein, this repeated pattern will run throughout its entire length, where it is known as the protein’s “backbone”. Amino acids differ, nevertheless, of their “side chain”, which is the name given to the atoms attached to this C-C-N backbone. The lower figure uses generic side chains labelled as R1, R2 and R3, which may very well be any amino acid. Within the upper figure, the central amino acid has a CH3 side chain – this identifies it because the amino acid Alanine, which is represented by the letter A. (Image source)

Despite the fact that we are able to write them as text strings, proteins aren’t actually a “language”, no less than not any form of language that Noam Chomsky would recognize. But they do have just a few language-like features that make them a really similar domain to text from a machine learning perspective: Proteins are long strings in a hard and fast, small alphabet, and although any string is feasible in theory, in practice only a really small subset of strings actually make “sense”. Random text is garbage, and random proteins are only a shapeless blob.

Also, information is lost for those who just consider parts of a protein in isolation, in the identical way that information is lost for those who just read a single sentence extracted from a bigger text. A region of a protein may only assume its natural shape within the presence of other parts of the protein that stabilize and proper that shape! Which means long-range interactions, of the type which are well-captured by global self-attention, are very essential to modelling proteins accurately.

At this point, hopefully you may have a vague idea of what a protein is and why biologists care about them a lot – despite their small ‘alphabet’ of amino acids, they’ve an enormous diversity of structure and performance, and with the ability to understand and predict those structures and functions just from taking a look at the raw ‘string’ of amino acids could be a particularly precious research tool.

Bringing it together: Machine learning with proteins

So now we have seen how transfer learning with language models works, and we have seen what proteins are. And once you may have that background, the subsequent step is not too hard – we are able to use the identical transfer learning ideas on proteins! As a substitute of pre-training a model on a task involving English text, we train it on a task where the inputs are proteins, but where plenty of training data is out there. Once we have done that, our model has hopefully learned lots in regards to the structure of proteins, in the identical way that language models learn lots in regards to the structure of language. That makes pre-trained protein models a main candidate for transferring to another protein-based task!

What form of machine learning tasks do biologists care about training protein models on? Essentially the most famous protein modelling task is protein folding. The duty here is to, given the amino acid chain like “MLKNV…”, predict the ultimate shape that protein will fold into. That is an enormously essential task, because accurately predicting the form and structure of a protein gives plenty of insights into what the protein does, and the way it does it.

People have been studying this problem since long before modern machine learning – a few of the earliest massive distributed computing projects like Folding@Home used atomic-level simulations at incredible spatial and temporal resolution to model protein folding, and there may be a whole field of protein crystallography that uses X-ray diffraction to look at the structure of proteins isolated from living cells.

Like plenty of other fields, though, the arrival of deep learning modified every part. AlphaFold and particularly AlphaFold2 used transformer deep learning models with a variety of protein-specific additions to realize exceptional results at predicting the structure of novel proteins just from the raw amino acid sequence. If protein folding is what you’re inquisitive about, we highly recommend trying out our ESMFold notebook – ESMFold is a brand new model that’s much like AlphaFold2, but it surely’s more of a ‘pure’ deep learning model that doesn’t require any external databases or search steps to run. Consequently, the setup process is far less painful and the model runs way more quickly, while still retaining outstanding accuracy.

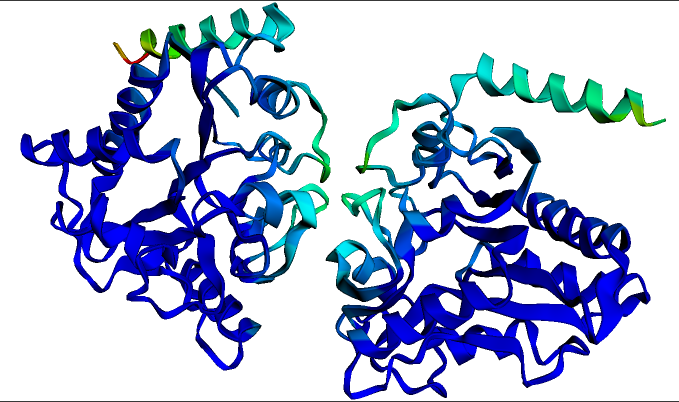

The expected structure for the homodimeric P. multocida protein Glucosamine-6-phosphate deaminase. This structure and visualization was generated in seconds using the ESMFold notebook linked above. Darker blue colors indicate regions of highest structure confidence.

Protein folding isn’t the one task of interest, though! There are a big selection of classification tasks that biologists might need to do with proteins – possibly they need to predict which a part of the cell that protein will operate in, or which amino acids within the protein will receive certain modifications after the protein is created. Within the language of machine learning, tasks like these are called sequence classification when you should classify the complete protein (for instance, predicting its subcellular localization), or token classification when you should classify each amino acid (for instance, predicting which individual amino acids will receive post-translational modifications).

The important thing takeaway, though, is that regardless that proteins are very different to language, they may be handled by almost the exact same machine learning approach – large-scale pre-training on an enormous database of protein sequences, followed by transfer learning to a big selection of tasks of interest where training data is perhaps much sparser. In truth, in some respects it’s even simpler than a big language model like BERT, because no complex splitting and parsing of words is required – proteins don’t have “word” divisions, and so the simplest approach is to easily convert each amino acid to a single input token.

Sounds cool, but I don’t know where to begin!

When you’re already conversant in deep learning, then you definately’ll find that the code for fine-tuning protein models looks extremely much like the code for fine-tuning language models. We’ve example notebooks for each PyTorch and TensorFlow for those who’re curious, and you possibly can get huge amounts of annotated data from open-access protein databases like UniProt, which has a REST API in addition to a pleasant web interface. Your principal difficulty shall be finding interesting research directions to explore, which is somewhat beyond the scope of this document – but I’m sure there are many biologists on the market who’d like to collaborate with you!

When you’re a biologist, then again, you almost certainly have several ideas for what you should try, but is perhaps just a little intimidated about diving into machine learning code. Don’t panic! We’ve designed the instance notebooks (PyTorch, TensorFlow) in order that the data-loading section is kind of independent of the remaining. Which means if you may have a sequence classification or token classification task in mind, all you’ll want to do is construct a listing of protein sequences and a listing of corresponding labels, after which swap out our data loading code for any code that loads or generates those lists.

Although the particular examples linked use ESM-2 as the bottom pre-trained model, because it’s the present cutting-edge, people in the sector are also more likely to be conversant in the Rost lab whose models like ProtBERT (paper link) were a few of the earliest models of their kind and have seen phenomenal interest from the bioinformatics community. Much of the code within the linked examples may be swapped over to using a base like ProtBERT just by changing the checkpoint path from facebook/esm2... to something like Rostlab/prot_bert.

Conclusion

The intersection of deep learning and biology goes to be an incredibly lively and fruitful field in the subsequent few years. Certainly one of the things that makes deep learning such a fast-moving field, though, is the speed with which individuals can reproduce results and adapt latest models for their very own use. In that spirit, for those who train a model that you’re thinking that could be useful to the community, please share it! The notebooks linked above contain code to upload models to the Hub, where they may be freely accessed and built upon by other researchers – along with the advantages to the sector, that is an excellent option to get visibility and citations on your associated papers as well. You may even make a live web demo with Spaces in order that other researchers can input protein sequences and get results without cost with no need to put in writing a single line of code. Good luck, and should Reviewer 2 be kind to you!