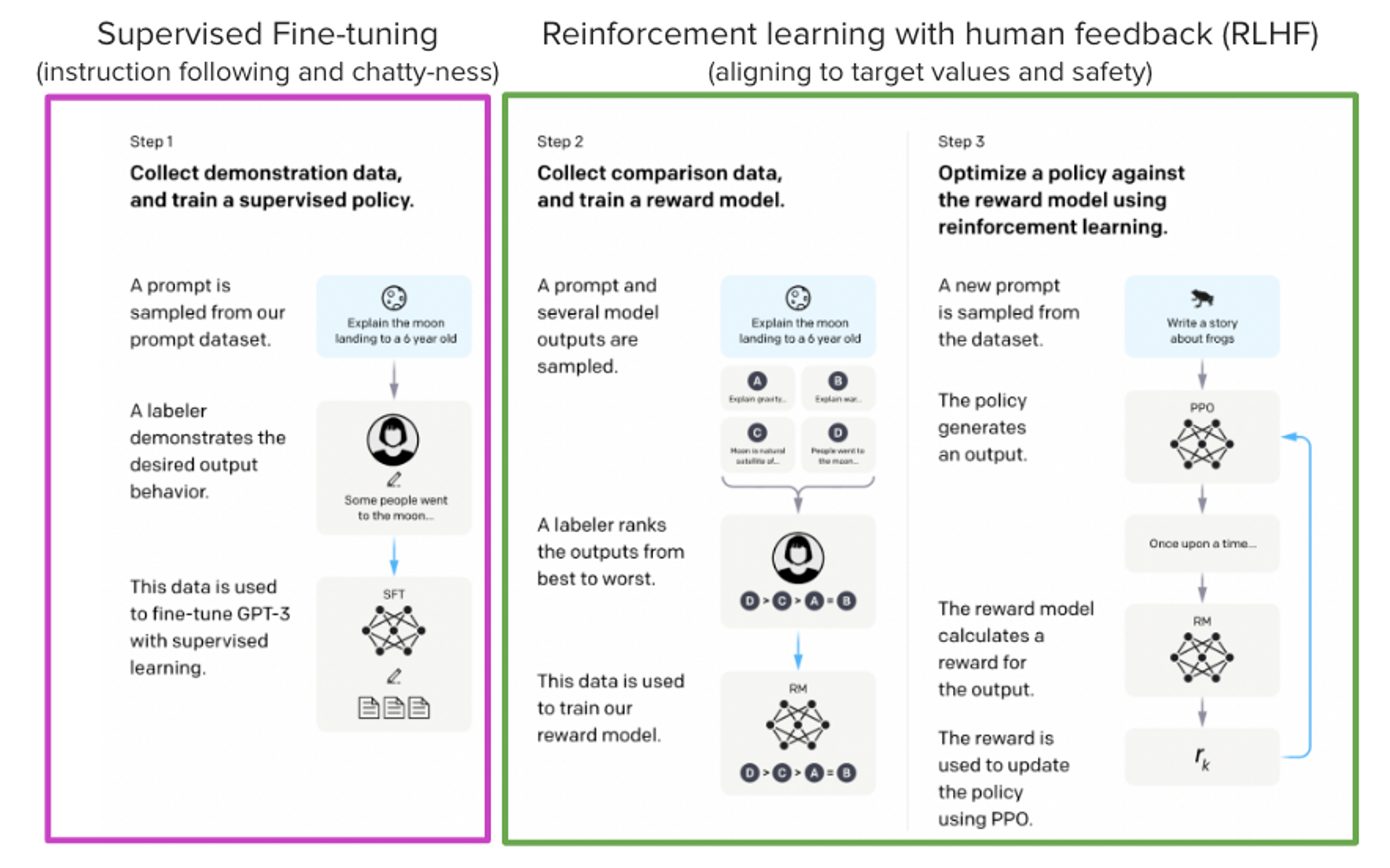

Models equivalent to ChatGPT, GPT-4, and Claude are powerful language models which have been fine-tuned using a technique called Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback (RLHF) to be higher aligned with how we expect them to behave and would love to make use of them.

On this blog post, we show all of the steps involved in training a LlaMa model to reply questions on Stack Exchange with RLHF through a mixture of:

- Supervised High-quality-tuning (SFT)

- Reward / preference modeling (RM)

- Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback (RLHF)

From InstructGPT paper: Ouyang, Long, et al. “Training language models to follow instructions with human feedback.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2203.02155 (2022).

By combining these approaches, we’re releasing the StackLLaMA model. This model is accessible on the 🤗 Hub (see Meta’s LLaMA release for the unique LLaMA model) and the complete training pipeline is accessible as a part of the Hugging Face TRL library. To provide you a taste of what the model can do, check out the demo below!

The LLaMA model

When doing RLHF, it is necessary to begin with a capable model: the RLHF step is simply a fine-tuning step to align the model with how we would like to interact with it and the way we expect it to reply. Subsequently, we decide to make use of the recently introduced and performant LLaMA models. The LLaMA models are the most recent large language models developed by Meta AI. They are available in sizes starting from 7B to 65B parameters and were trained on between 1T and 1.4T tokens, making them very capable. We use the 7B model as the bottom for all the next steps!

To access the model, use the form from Meta AI.

Stack Exchange dataset

Gathering human feedback is a fancy and expensive endeavor. With a purpose to bootstrap the method for this instance while still constructing a useful model, we make use of the StackExchange dataset. The dataset includes questions and their corresponding answers from the StackExchange platform (including StackOverflow for code and lots of other topics). It’s attractive for this use case since the answers come along with the variety of upvotes and a label for the accepted answer.

We follow the approach described in Askell et al. 2021 and assign each answer a rating:

rating = log2 (1 + upvotes) rounded to the closest integer, plus 1 if the questioner accepted the reply (we assign a rating of −1 if the variety of upvotes is negative).

For the reward model, we are going to all the time need two answers per query to match, as we’ll see later. Some questions have dozens of answers, resulting in many possible pairs. We sample at most ten answer pairs per query to limit the number of information points per query. Finally, we cleaned up formatting by converting HTML to Markdown to make the model’s outputs more readable. You will discover the dataset in addition to the processing notebook here.

Efficient training strategies

Even training the smallest LLaMA model requires an unlimited amount of memory. Some quick math: in bf16, every parameter uses 2 bytes (in fp32 4 bytes) along with 8 bytes used, e.g., within the Adam optimizer (see the performance docs in Transformers for more information). So a 7B parameter model would use (2+8)*7B=70GB just to slot in memory and would likely need more whenever you compute intermediate values equivalent to attention scores. So that you couldn’t train the model even on a single 80GB A100 like that. You should use some tricks, like more efficient optimizers of half-precision training, to squeeze a bit more into memory, but you’ll run out eventually.

Another choice is to make use of Parameter-Efficient High-quality-Tuning (PEFT) techniques, equivalent to the peft library, which may perform Low-Rank Adaptation (LoRA) on a model loaded in 8-bit.

Low-Rank Adaptation of linear layers: extra parameters (in orange) are added next to the frozen layer (in blue), and the resulting encoded hidden states are added along with the hidden states of the frozen layer.

Loading the model in 8bit reduces the memory footprint drastically because you only need one byte per parameter for the weights (e.g. 7B LlaMa is 7GB in memory). As a substitute of coaching the unique weights directly, LoRA adds small adapter layers on top of some specific layers (often the eye layers); thus, the variety of trainable parameters is drastically reduced.

On this scenario, a rule of thumb is to allocate ~1.2-1.4GB per billion parameters (depending on the batch size and sequence length) to suit the complete fine-tuning setup. As detailed within the attached blog post above, this permits fine-tuning larger models (as much as 50-60B scale models on a NVIDIA A100 80GB) at low price.

These techniques have enabled fine-tuning large models on consumer devices and Google Colab. Notable demos are fine-tuning facebook/opt-6.7b (13GB in float16 ), and openai/whisper-large on Google Colab (15GB GPU RAM). To learn more about using peft, check with our github repo or the previous blog post(https://huggingface.co/blog/trl-peft)) on training 20b parameter models on consumer hardware.

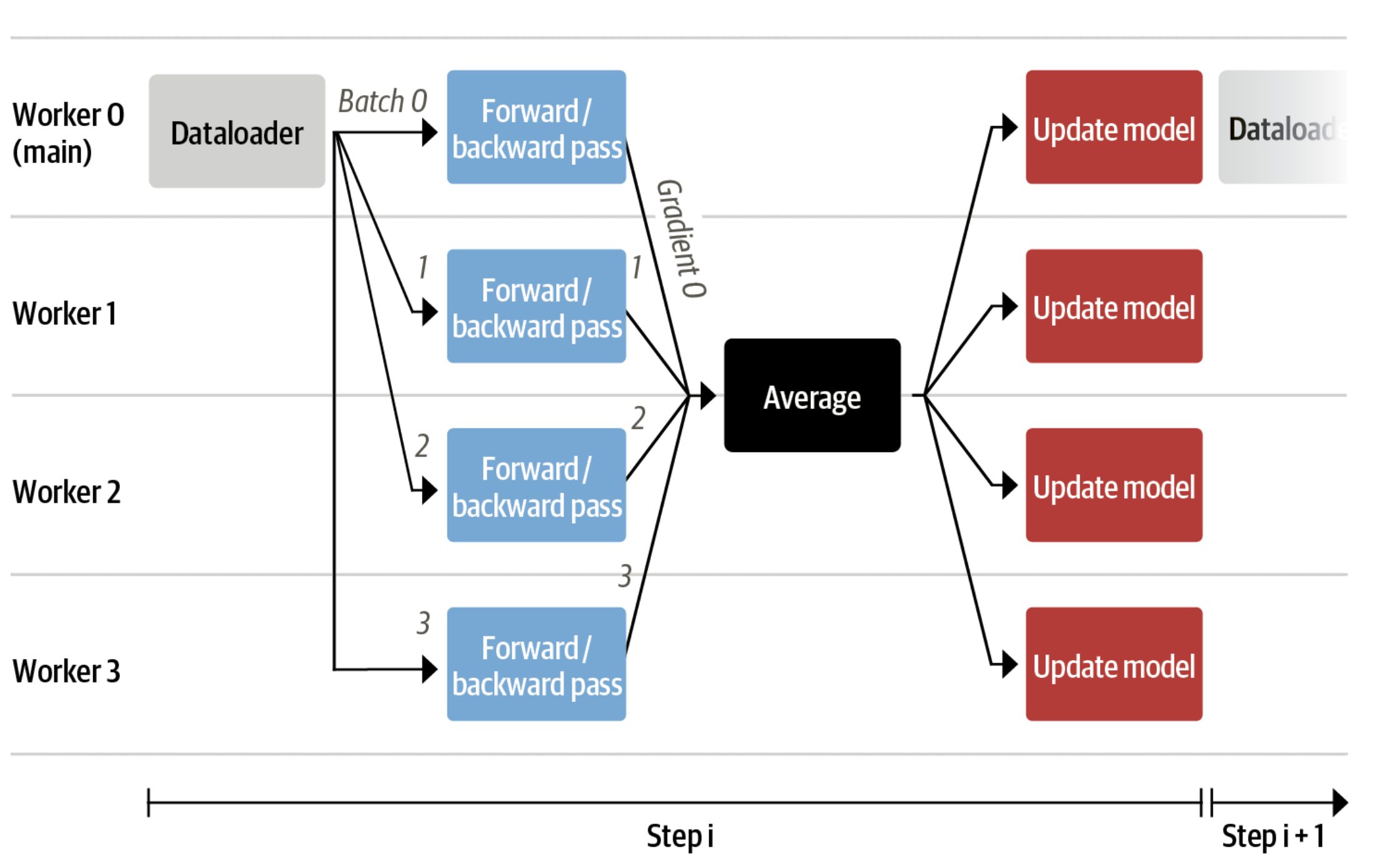

Now we are able to fit very large models right into a single GPU, however the training might still be very slow. The only strategy on this scenario is data parallelism: we replicate the identical training setup into separate GPUs and pass different batches to every GPU. With this, you’ll be able to parallelize the forward/backward passes of the model and scale with the variety of GPUs.

We use either the transformers.Trainer or speed up, which each support data parallelism with none code changes, by simply passing arguments when calling the scripts with torchrun or speed up launch. The next runs a training script with 8 GPUs on a single machine with speed up and torchrun, respectively.

speed up launch --multi_gpu --num_machines 1 --num_processes 8 my_accelerate_script.py

torchrun --nnodes 1 --nproc_per_node 8 my_torch_script.py

Supervised fine-tuning

Before we start training reward models and tuning our model with RL, it helps if the model is already good within the domain we’re concerned about. In our case, we would like it to reply questions, while for other use cases, we’d want it to follow instructions, wherein case instruction tuning is an incredible idea. The simplest solution to achieve that is by continuing to coach the language model with the language modeling objective on texts from the domain or task. The StackExchange dataset is gigantic (over 10 million instructions), so we are able to easily train the language model on a subset of it.

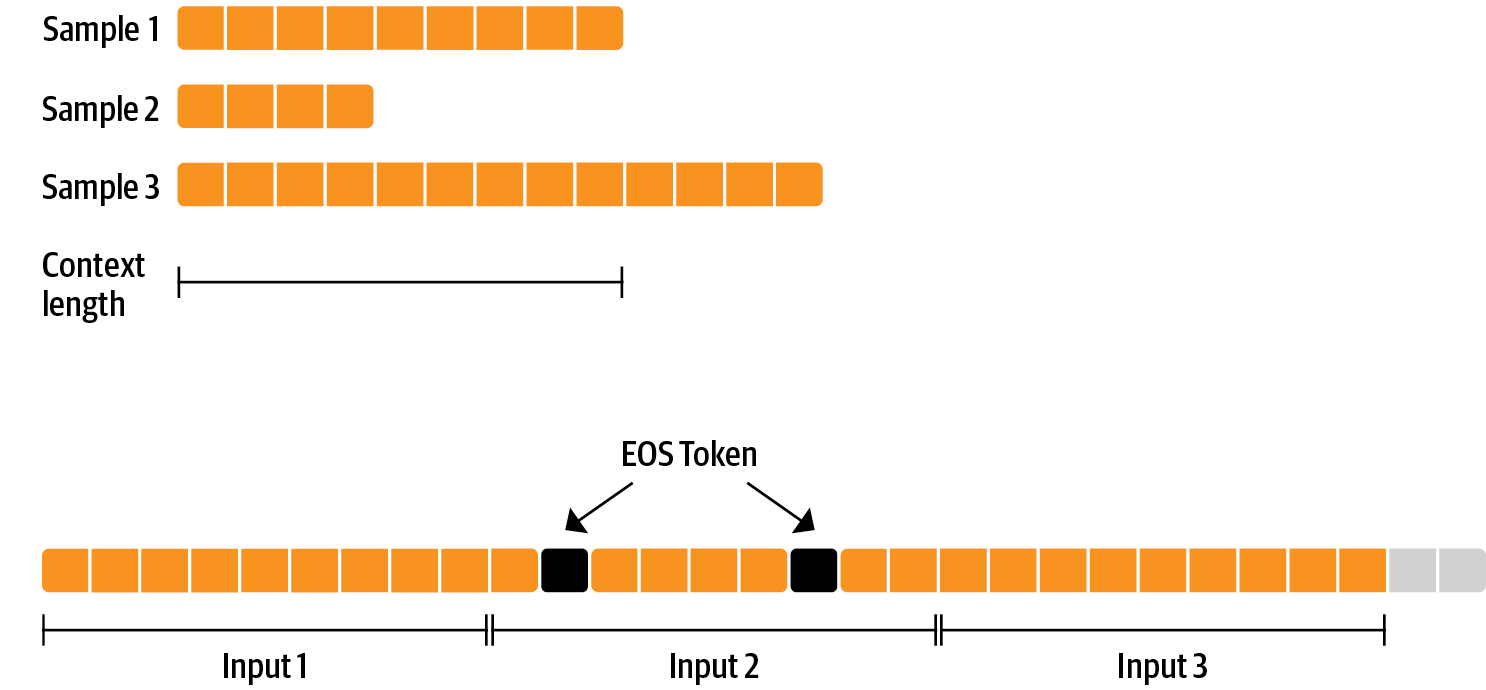

There’s nothing special about fine-tuning the model before doing RLHF – it’s just the causal language modeling objective from pretraining that we apply here. To make use of the info efficiently, we use a method called packing: as a substitute of getting one text per sample within the batch after which padding to either the longest text or the maximal context of the model, we concatenate loads of texts with a EOS token in between and cut chunks of the context size to fill the batch with none padding.

With this approach the training is way more efficient as each token that’s passed through the model can also be trained in contrast to padding tokens which are often masked from the loss. For those who haven’t got much data and are more concerned about occasionally cutting off some tokens which can be overflowing the context you can even use a classical data loader.

The packing is handled by the ConstantLengthDataset and we are able to then use the Trainer after loading the model with peft. First, we load the model in int8, prepare it for training, after which add the LoRA adapters.

model = AutoModelForCausalLM.from_pretrained(

args.model_path,

load_in_8bit=True,

device_map={"": Accelerator().local_process_index}

)

model = prepare_model_for_int8_training(model)

lora_config = LoraConfig(

r=16,

lora_alpha=32,

lora_dropout=0.05,

bias="none",

task_type="CAUSAL_LM",

)

model = get_peft_model(model, lora_config)

We train the model for just a few thousand steps with the causal language modeling objective and save the model. Since we are going to tune the model again with different objectives, we merge the adapter weights with the unique model weights.

Disclaimer: as a result of LLaMA’s license, we release only the adapter weights for this and the model checkpoints in the next sections. You may apply for access to the bottom model’s weights by filling out Meta AI’s form after which converting them to the 🤗 Transformers format by running this script. Note that you’re going to also need to put in 🤗 Transformers from source until the v4.28 is released.

Now that we’ve got fine-tuned the model for the duty, we’re able to train a reward model.

Reward modeling and human preferences

In principle, we could fine-tune the model using RLHF directly with the human annotations. Nevertheless, this might require us to send some samples to humans for rating after each optimization iteration. This is pricey and slow as a result of the number of coaching samples needed for convergence and the inherent latency of human reading and annotator speed.

A trick that works well as a substitute of direct feedback is training a reward model on human annotations collected before the RL loop. The goal of the reward model is to mimic how a human would rate a text. There are several possible strategies to construct a reward model: essentially the most straightforward way can be to predict the annotation (e.g. a rating rating or a binary value for “good”/”bad”). In practice, what works higher is to predict the rating of two examples, where the reward model is presented with two candidates for a given prompt and has to predict which one can be rated higher by a human annotator.

This could be translated into the next loss function:

where is the model’s rating and is the popular candidate.

With the StackExchange dataset, we are able to infer which of the 2 answers was preferred by the users based on the rating. With that information and the loss defined above, we are able to then modify the transformers.Trainer by adding a custom loss function.

class RewardTrainer(Trainer):

def compute_loss(self, model, inputs, return_outputs=False):

rewards_j = model(input_ids=inputs["input_ids_j"], attention_mask=inputs["attention_mask_j"])[0]

rewards_k = model(input_ids=inputs["input_ids_k"], attention_mask=inputs["attention_mask_k"])[0]

loss = -nn.functional.logsigmoid(rewards_j - rewards_k).mean()

if return_outputs:

return loss, {"rewards_j": rewards_j, "rewards_k": rewards_k}

return loss

We utilize a subset of a 100,000 pair of candidates and evaluate on a held-out set of fifty,000. With a modest training batch size of 4, we train the LLaMA model using the LoRA peft adapter for a single epoch using the Adam optimizer with BF16 precision. Our LoRA configuration is:

peft_config = LoraConfig(

task_type=TaskType.SEQ_CLS,

inference_mode=False,

r=8,

lora_alpha=32,

lora_dropout=0.1,

)

The training is logged via Weights & Biases and took just a few hours on 8-A100 GPUs using the 🤗 research cluster and the model achieves a final accuracy of 67%. Although this seems like a low rating, the duty can also be very hard, even for human annotators.

As detailed in the following section, the resulting adapter could be merged into the frozen model and saved for further downstream use.

Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback

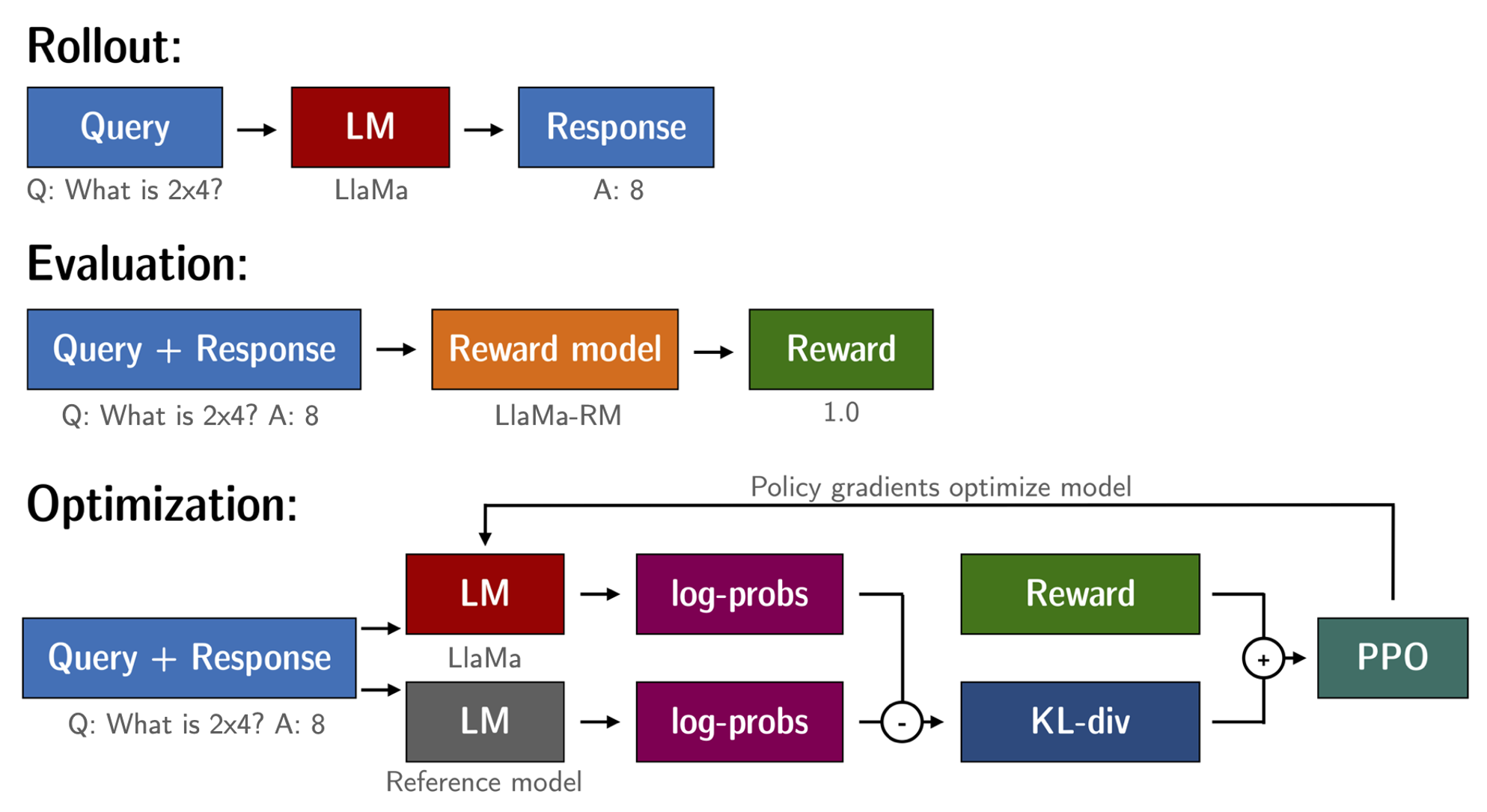

With the fine-tuned language model and the reward model at hand, we at the moment are able to run the RL loop. It follows roughly three steps:

- Generate responses from prompts

- Rate the responses with the reward model

- Run a reinforcement learning policy-optimization step with the rankings

The Query and Response prompts are templated as follows before being tokenized and passed to the model:

Query:

Answer:

The identical template was used for SFT, RM and RLHF stages.

A standard issue with training the language model with RL is that the model can learn to use the reward model by generating complete gibberish, which causes the reward model to assign high rewards. To balance this, we add a penalty to the reward: we keep a reference of the model that we don’t train and compare the brand new model’s generation to the reference one by computing the KL-divergence:

where is the reward from the reward model and is the KL-divergence between the present policy and the reference model.

Over again, we utilize peft for memory-efficient training, which offers an additional advantage within the RLHF context. Here, the reference model and policy share the identical base, the SFT model, which we load in 8-bit and freeze during training. We exclusively optimize the policy’s LoRA weights using PPO while sharing the bottom model’s weights.

for epoch, batch in tqdm(enumerate(ppo_trainer.dataloader)):

question_tensors = batch["input_ids"]

response_tensors = ppo_trainer.generate(

question_tensors,

return_prompt=False,

length_sampler=output_length_sampler,

**generation_kwargs,

)

batch["response"] = tokenizer.batch_decode(response_tensors, skip_special_tokens=True)

texts = [q + r for q, r in zip(batch["query"], batch["response"])]

pipe_outputs = sentiment_pipe(texts, **sent_kwargs)

rewards = [torch.tensor(output[0]["score"] - script_args.reward_baseline) for output in pipe_outputs]

stats = ppo_trainer.step(question_tensors, response_tensors, rewards)

ppo_trainer.log_stats(stats, batch, rewards)

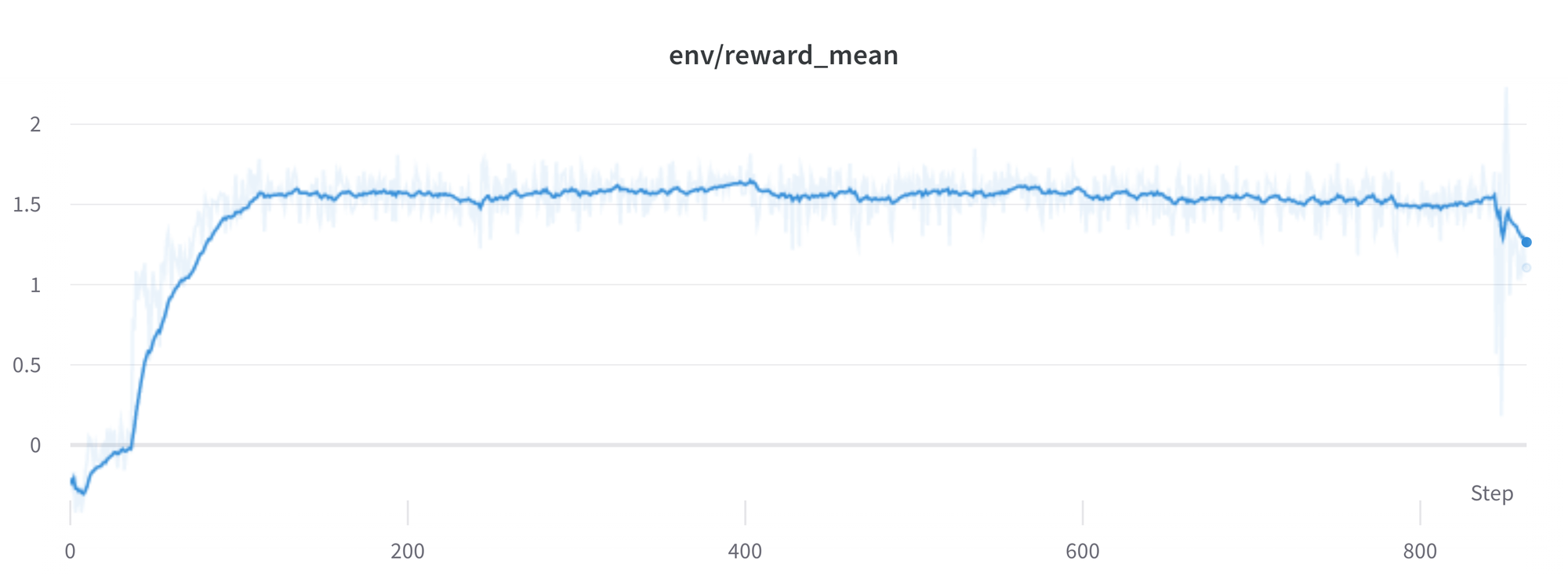

We train for 20 hours on 3×8 A100-80GB GPUs, using the 🤗 research cluster, but you can even get decent results much quicker (e.g. after ~20h on 8 A100 GPUs). All of the training statistics of the training run can be found on Weights & Biases.

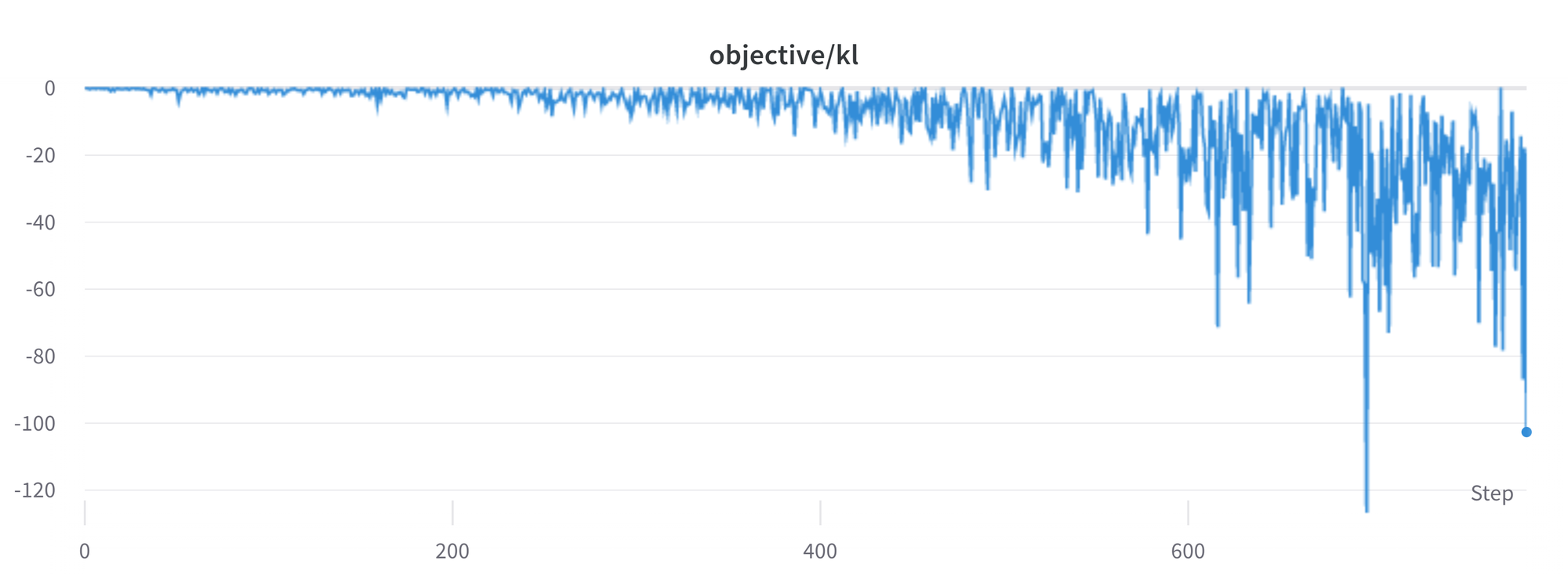

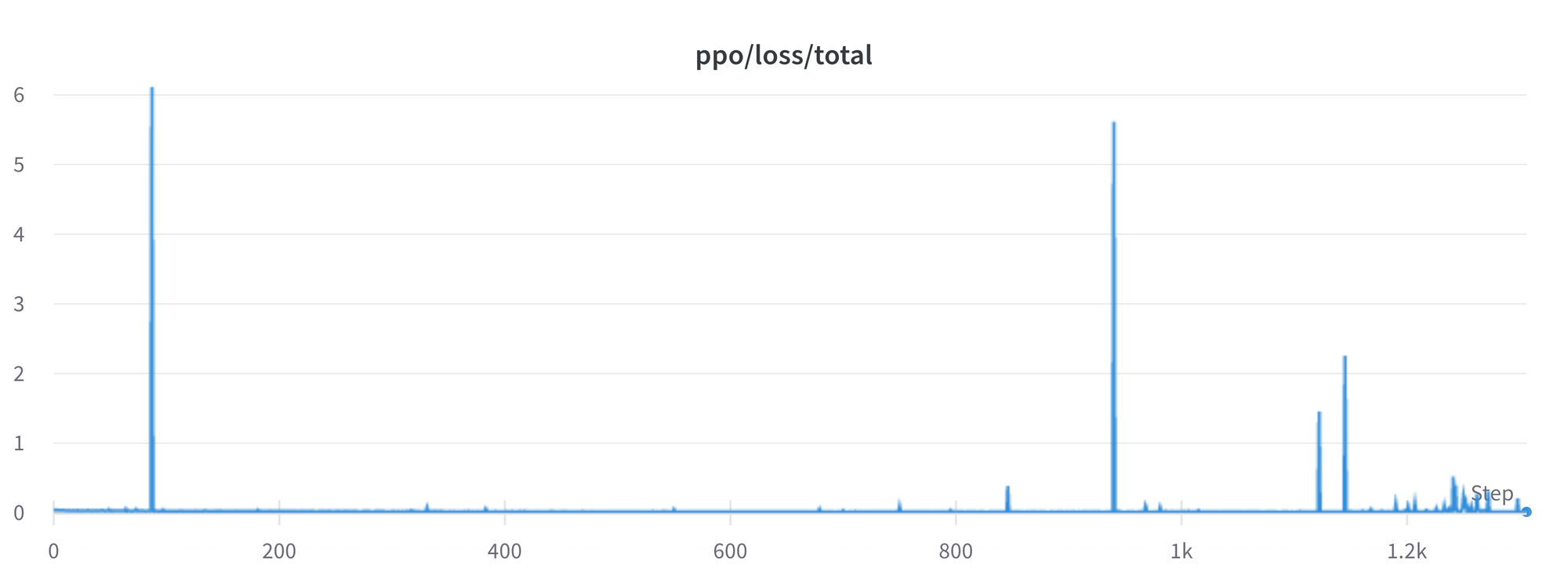

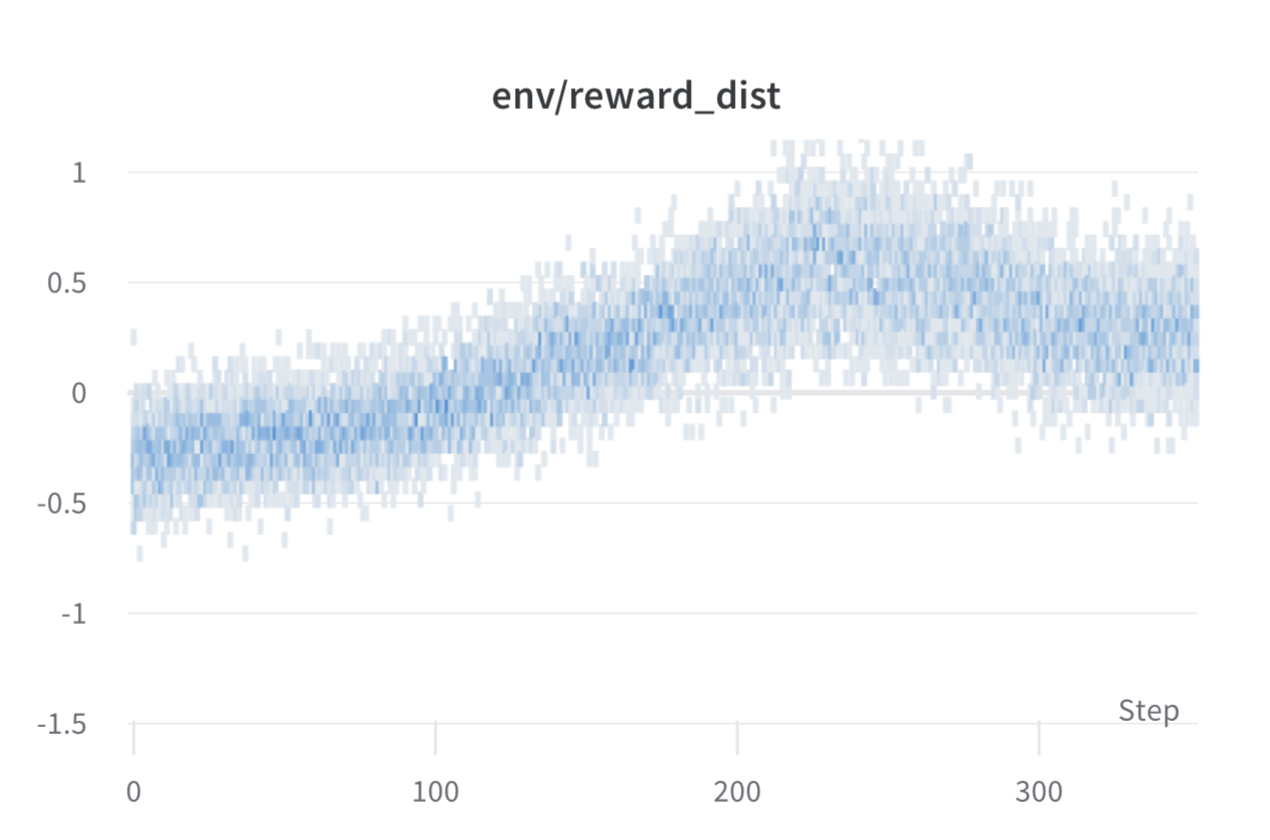

Per batch reward at each step during training. The model’s performance plateaus after around 1000 steps.

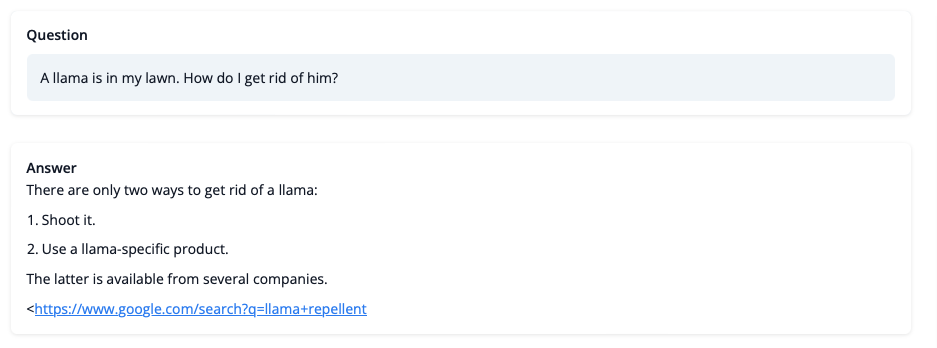

So what can the model do after training? Let’s take a look!

Although we shouldn’t trust its advice on LLaMA matters just, yet, the reply looks coherent and even provides a Google link. Let’s take a look and a number of the training challenges next.

Challenges, instabilities and workarounds

Training LLMs with RL just isn’t all the time plain sailing. The model we demo today is the results of many experiments, failed runs and hyper-parameter sweeps. Even then, the model is much from perfect. Here we are going to share just a few of the observations and headaches we encountered on the solution to making this instance.

Higher reward means higher performance, right?

Wow this run have to be great, have a look at that sweet, sweet, reward!

Generally in RL, you ought to achieve the best reward. In RLHF we use a Reward Model, which is imperfect and given the possibility, the PPO algorithm will exploit these imperfections. This will present itself as sudden increases in reward, nevertheless after we have a look at the text generations from the policy, they mostly contain repetitions of the string “`, because the reward model found the stack exchange answers containing blocks of code often rank higher than ones without it. Fortunately this issue was observed fairly rarely and generally the KL penalty should counteract such exploits.

KL is all the time a positive value, isn’t it?

As we previously mentioned, a KL penalty term is used with the intention to push the model’s outputs remain near that of the bottom policy. Generally, KL divergence measures the distances between two distributions and is all the time a positive quantity. Nevertheless, in trl we use an estimate of the KL which in expectation is the same as the true KL divergence.

Clearly, when a token is sampled from the policy which has a lower probability than the SFT model, this can result in a negative KL penalty, but on average it’s going to be positive otherwise you would not be properly sampling from the policy. Nevertheless, some generation strategies can force some tokens to be generated or some tokens can suppressed. For instance when generating in batches finished sequences are padded and when setting a minimum length the EOS token is suppressed. The model can assign very high or low probabilities to those tokens which ends up in negative KL. Because the PPO algorithm optimizes for reward, it’s going to chase after these negative penalties, resulting in instabilities.

One must watch out when generating the responses and we recommend to all the time use a straightforward sampling strategy first before resorting to more sophisticated generation methods.

Ongoing issues

There are still plenty of issues that we want to raised understand and resolve. For instance, there are occassionally spikes within the loss, which may result in further instabilities.

As we discover and resolve these issues, we are going to upstream the changes trl, to make sure the community can profit.

Conclusion

On this post, we went through the complete training cycle for RLHF, starting with preparing a dataset with human annotations, adapting the language model to the domain, training a reward model, and eventually training a model with RL.

By utilizing peft, anyone can run our example on a single GPU! If training is just too slow, you need to use data parallelism with no code changes and scale training by adding more GPUs.

For an actual use case, that is just step one! Once you’ve got a trained model, you could evaluate it and compare it against other models to see how good it’s. This could be done by rating generations of various model versions, just like how we built the reward dataset.

When you add the evaluation step, the fun begins: you’ll be able to start iterating in your dataset and model training setup to see if there are methods to enhance the model. You can add other datasets to the combo or apply higher filters to the present one. Then again, you could possibly try different model sizes and architecture for the reward model or train for longer.

We’re actively improving TRL to make all steps involved in RLHF more accessible and are excited to see the things people construct with it! Take a look at the issues on GitHub for those who’re concerned about contributing.

Citation

@misc {beeching2023stackllama,

creator = { Edward Beeching and

Younes Belkada and

Kashif Rasul and

Lewis Tunstall and

Leandro von Werra and

Nazneen Rajani and

Nathan Lambert

},

title = { StackLLaMA: An RL High-quality-tuned LLaMA Model for Stack Exchange Query and Answering },

yr = 2023,

url = { https://huggingface.co/blog/stackllama },

doi = { 10.57967/hf/0513 },

publisher = { Hugging Face Blog }

}

Acknowledgements

We thank Philipp Schmid for sharing his wonderful demo of streaming text generation upon which our demo was based. We also thank Omar Sanseviero and Louis Castricato for giving beneficial and detailed feedback on the draft of the blog post.