People who find themselves taken with document-level near-deduplication at a big scale, and have some understanding of hashing, graph and text processing.

Motivations

It is crucial to handle our data before feeding it to the model, not less than Large Language Model in our case, because the old saying goes, garbage in, garbage out. Although it’s increasingly difficult to achieve this with headline-grabbing models (or should we are saying APIs) creating an illusion that data quality matters less.

Considered one of the issues we face in each BigScience and BigCode for data quality is duplication, including possible benchmark contamination. It has been shown that models are inclined to output training data verbatim when there are a lot of duplicates[1] (though it’s less clear in another domains[2]), and it also makes the model vulnerable to privacy attacks[1]. Moreover, some typical benefits of deduplication also include:

- Efficient training: You’ll be able to achieve the identical, and sometimes higher, performance with less training steps[3] [4].

- Prevent possible data leakage and benchmark contamination: Non-zero duplicates discredit your evaluations and potentially make so-called improvement a false claim.

- Accessibility. Most of us cannot afford to download or transfer 1000’s of gigabytes of text repeatedly, not to say training a model with it. Deduplication, for a fix-sized dataset, makes it easier to review, transfer and collaborate with.

From BigScience to BigCode

Allow me to share a story first on how I jumped on this near-deduplication quest, how the outcomes have progressed, and what lessons I actually have learned along the best way.

It began with a conversation on LinkedIn when BigScience had already began for a few months. Huu Nguyen approached me when he noticed my pet project on GitHub, asking me if I were taken with working on deduplication for BigScience. In fact, my answer was a yes, completely blind to just how much effort shall be required alone attributable to the sheer mount of the information.

It was fun and difficult at the identical time. It’s difficult in a way that I didn’t really have much research experience with that sheer scale of knowledge, and everybody was still welcoming and trusting you with 1000’s of dollars of cloud compute budget. Yes, I needed to get up from my sleep to double-check that I had turned off those machines several times. In consequence, I needed to learn on the job through all of the trials and errors, which in the long run opened me to a brand new perspective that I do not think I might ever have if it weren’t for BigScience.

Moving forward, one yr later, I’m putting what I actually have learned back into BigCode, working on even larger datasets. Along with LLMs which might be trained for English[3], we’ve got confirmed that deduplication improves code models too[4], while using a much smaller dataset. And now, I’m sharing what I actually have learned with you, my dear reader, and hopefully, you may also get a way of what is going on behind the scene of BigCode through the lens of deduplication.

In case you have an interest, here is an updated version of the deduplication comparison that we began in BigScience:

| Dataset | Input Size | Output Size or Deduction | Level | Method | Parameters | Language | Time |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OpenWebText2[5] | After URL dedup: 193.89 GB (69M) | After MinHashLSH: 65.86 GB (17M) | URL + Document | URL(Exact) + Document(MinHash LSH) | English | ||

| Pile-CC[5] | ~306 GB | 227.12 GiB (~55M) | Document | Document(MinHash LSH) | English | “several days” | |

| BNE5[6] | 2TB | 570 GB | Document | Onion | 5-gram | Spanish | |

| MassiveText[7] | 0.001 TB ~ 2.1 TB | Document | Document(Exact + MinHash LSH) | English | |||

| CC100-XL[8] | 0.01 GiB ~ 3324.45 GiB | URL + Paragraph | URL(Exact) + Paragraph(Exact) | SHA-1 | Multilingual | ||

| C4[3] | 806.92 GB (364M) | 3.04% ~ 7.18% ↓ (train) | Substring or Document | Substring(Suffix Array) or Document(MinHash) | Suffix Array: 50-token, MinHash: | English | |

| Real News[3] | ~120 GiB | 13.63% ~ 19.4% ↓ (train) | Same as C4 | Same as C4 | Same as C4 | English | |

| LM1B[3] | ~4.40 GiB (30M) | 0.76% ~ 4.86% ↓ (train) | Same as C4 | Same as C4 | Same as C4 | English | |

| WIKI40B[3] | ~2.9M | 0.39% ~ 2.76% ↓ (train) | Same as C4 | Same as C4 | Same as C4 | English | |

| The BigScience ROOTS Corpus[9] | 0.07% ~ 2.7% ↓ (document) + 10.61%~32.30% ↓ (substring) | Document + Substring | Document (SimHash) + Substring (Suffix Array) | SimHash: 6-grams, hamming distance of 4, Suffix Array: 50-token | Multilingual | 12 hours ~ few days |

That is the one for code datasets we created for BigCode as well. Model names are used when the dataset name is not available.

| Model | Method | Parameters | Level |

|---|---|---|---|

| InCoder[10] | Exact | Alphanumeric tokens/md5 + Bloom filter | Document |

| CodeGen[11] | Exact | SHA256 | Document |

| AlphaCode[12] | Exact | ignore whiespaces | Document |

| PolyCode[13] | Exact | SHA256 | Document |

| PaLM Coder[14] | Levenshtein distance | Document | |

| CodeParrot[15] | MinHash + LSH | Document | |

| The Stack[16] | MinHash + LSH | Document |

MinHash + LSH parameters :

- variety of permutations/hashes

- Jaccard similarity threshold

- n-gram/shingle size

- variety of bands

- variety of rows

To get a way of how those parameters might impact your results, here is an easy demo for instance the computation mathematically: MinHash Math Demo.

MinHash Walkthrough

On this section, we are going to cover each step of MinHash, the one utilized in BigCode, and potential scaling issues and solutions. We are going to show the workflow via one example of three documents in English:

| doc_id | content |

|---|---|

| 0 | Deduplication is a lot fun! |

| 1 | Deduplication is a lot fun and simple! |

| 2 | I wish spider dog[17] is a thing. |

The everyday workflow of MinHash is as follows:

- Shingling (tokenization) and fingerprinting (MinHashing), where we map each document right into a set of hashes.

- Locality-sensitive hashing (LSH). This step is to cut back the variety of comparisons by grouping documents with similar bands together.

- Duplicate removal. This step is where we resolve which duplicated documents to maintain or remove.

Shingles

Like in most applications involving text, we want to start with tokenization. N-grams, a.k.a. shingles, are sometimes used. In our example, we shall be using word-level tri-grams, with none punctuations. We are going to circle back to how the scale of ngrams impacts the performance in a later section.

| doc_id | shingles |

|---|---|

| 0 | {“Deduplication is so”, “is a lot”, “a lot fun”} |

| 1 | {‘a lot fun’, ‘fun and simple’, ‘Deduplication is so’, ‘is a lot’} |

| 2 | {‘dog is a’, ‘is a thing’, ‘wish spider dog’, ‘spider dog is’, ‘I wish spider’} |

This operation has a time complexity of where is the variety of documents and is the length of the document. In other words, it’s linearly depending on the scale of the dataset. This step may be easily scaled by parallelization by multiprocessing or distributed computation.

Fingerprint Computation

In MinHash, each shingle will typically either be 1) hashed multiple times with different hash functions, or 2) permuted multiple times using one hash function. Here, we decide to permute each hash 5 times. More variants of MinHash may be present in MinHash – Wikipedia.

| shingle | permuted hashes |

|---|---|

| Deduplication is so | [403996643, 2764117407, 3550129378, 3548765886, 2353686061] |

| is a lot | [3594692244, 3595617149, 1564558780, 2888962350, 432993166] |

| a lot fun | [1556191985, 840529008, 1008110251, 3095214118, 3194813501] |

Taking the minimum value of every column inside each document — the “Min” a part of the “MinHash”, we arrive at the ultimate MinHash for this document:

| doc_id | minhash |

|---|---|

| 0 | [403996643, 840529008, 1008110251, 2888962350, 432993166] |

| 1 | [403996643, 840529008, 1008110251, 1998729813, 432993166] |

| 2 | [166417565, 213933364, 1129612544, 1419614622, 1370935710] |

Technically, we do not have to make use of the minimum value of every column, however the minimum value is essentially the most common alternative. Other order statistics similar to maximum, kth smallest, or kth largest may be used as well[21].

In implementation, you may easily vectorize these steps with numpy and expect to have a time complexity of where is your variety of permutations. Code modified based on Datasketch.

def embed_func(

content: str,

idx: int,

*,

num_perm: int,

ngram_size: int,

hashranges: List[Tuple[int, int]],

permutations: np.ndarray,

) -> Dict[str, Any]:

a, b = permutations

masks: np.ndarray = np.full(shape=num_perm, dtype=np.uint64, fill_value=MAX_HASH)

tokens: Set[str] = {" ".join(t) for t in ngrams(NON_ALPHA.split(content), ngram_size)}

hashvalues: np.ndarray = np.array([sha1_hash(token.encode("utf-8")) for token in tokens], dtype=np.uint64)

permuted_hashvalues = np.bitwise_and(

((hashvalues * np.tile(a, (len(hashvalues), 1)).T).T + b) % MERSENNE_PRIME, MAX_HASH

)

hashvalues = np.vstack([permuted_hashvalues, masks]).min(axis=0)

Hs = [bytes(hashvalues[start:end].byteswap().data) for start, end in hashranges]

return {"__signatures__": Hs, "__id__": idx}

In the event you are aware of Datasketch, you may ask, why will we hassle to strip all the good high-level functions the library provides? It just isn’t because we wish to avoid adding dependencies, but because we intend to squeeze as much CPU computation as possible during parallelization. Fusing few steps into one function call enables us to utilize our compute resources higher.

Since one document’s calculation just isn’t depending on the rest. parallelization alternative can be using the map function from the datasets library:

embedded = ds.map(

function=embed_func,

fn_kwargs={

"num_perm": args.num_perm,

"hashranges": HASH_RANGES,

"ngram_size": args.ngram,

"permutations": PERMUTATIONS,

},

input_columns=[args.column],

remove_columns=ds.column_names,

num_proc=os.cpu_count(),

with_indices=True,

desc="Fingerprinting...",

)

After the fingerprint calculation, one particular document is mapped to 1 array of integer values. To work out what documents are much like one another, we want to group them based on such fingerprints. Entering the stage, Locality Sensitive Hashing (LSH).

Locality Sensitive Hashing

LSH breaks the fingerprint array into bands, each band containing the identical variety of rows. If there may be any hash values left, it would be ignored. Let’s use bands and rows to group those documents:

| doc_id | minhash | bands |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | [403996643, 840529008, 1008110251, 2888962350, 432993166] | [0:[403996643, 840529008], 1:[1008110251, 2888962350]] |

| 1 | [403996643, 840529008, 1008110251, 1998729813, 432993166] | [0:[403996643, 840529008], 1:[1008110251, 1998729813]] |

| 2 | [166417565, 213933364, 1129612544, 1419614622, 1370935710] | [0:[166417565, 213933364], 1:[1129612544, 1419614622]] |

If two documents share the identical hashes in a band at a selected location (band index), they shall be clustered into the identical bucket and shall be regarded as candidates.

| band index | band value | doc_ids |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | [403996643, 840529008] | 0, 1 |

| 1 | [1008110251, 2888962350] | 0 |

| 1 | [1008110251, 1998729813] | 1 |

| 0 | [166417565, 213933364] | 2 |

| 1 | [1129612544, 1419614622] | 2 |

For every row within the doc_ids column, we will generate candidate pairs by pairing every two of them. From the above table, we will generate one candidate pair: (0, 1).

Beyond Duplicate Pairs

That is where many deduplication descriptions in papers or tutorials stop. We’re still left with the query of what to do with them. Generally, we will proceed with two options:

- Double-check their actual Jaccard similarities by calculating their shingle overlap, attributable to the estimation nature of MinHash. The Jaccard Similarity of two sets is defined as the scale of the intersection divided by the scale of the union. And now it becomes far more doable than computing all-pair similarities, because we will focus just for documents inside a cluster. This can also be what we initially did for BigCode, which worked reasonably well.

- Treat them as true positives. You most likely already noticed the difficulty here: the Jaccard similarity is not transitive, meaning is comparable to and is comparable to , but and don’t obligatory share the similarity. Nevertheless, our experiments from The Stack show that treating all of them as duplicates improves the downstream model’s performance the very best. And now we progressively moved towards this method as a substitute, and it saves time as well. But to use this to your dataset, we still recommend going over your dataset and looking out at your duplicates, after which making a data-driven decision.

From such pairs, whether or not they are validated or not, we will now construct a graph with those pairs as edges, and duplicates shall be clustered into communities or connected components. When it comes to implementation, unfortunately, that is where datasets couldn’t help much because now we want something like a groupby where we will cluster documents based on their band offset and band values. Listed below are some options we’ve got tried:

Option 1: Iterate the datasets the old-fashioned way and collect edges. Then use a graph library to do community detection or connected component detection.

This didn’t scale well in our tests, and the explanations are multifold. First, iterating the entire dataset is slow and memory consuming at a big scale. Second, popular graph libraries like graphtool or networkx have loads of overhead for graph creation.

Option 2: Use popular python frameworks similar to dask to permit more efficient groupby operations.

But then you definitely still have problems of slow iteration and slow graph creation.

Option 3: Iterate the dataset, but use a union find data structure to cluster documents.

This adds negligible overhead to the iteration, and it really works relatively well for medium datasets.

for table in tqdm(HASH_TABLES, dynamic_ncols=True, desc="Clustering..."):

for cluster in table.values():

if len(cluster) <= 1:

proceed

idx = min(cluster)

for x in cluster:

uf.union(x, idx)

Option 4: For big datasets, use Spark.

We already know that steps as much as the LSH part may be parallelized, which can also be achievable in Spark. Along with that, Spark supports distributed groupBy out of the box, and it is usually straightforward to implement algorithms like [18] for connected component detection. In the event you are wondering why we didn’t use Spark’s implementation of MinHash, the reply is that every one our experiments to date stemmed from Datasketch, which uses a completely different implementation than Spark, and we wish to make sure that we stock on the teachings and insights learned from that without going into one other rabbit hole of ablation experiments.

edges = (

records.flatMap(

lambda x: generate_hash_values(

content=x[1],

idx=x[0],

num_perm=args.num_perm,

ngram_size=args.ngram_size,

hashranges=HASH_RANGES,

permutations=PERMUTATIONS,

)

)

.groupBy(lambda x: (x[0], x[1]))

.flatMap(lambda x: generate_edges([i[2] for i in x[1]]))

.distinct()

.cache()

)

An easy connected component algorithm based on [18] implemented in Spark.

a = edges

while True:

b = a.flatMap(large_star_map).groupByKey().flatMap(large_star_reduce).distinct().cache()

a = b.map(small_star_map).groupByKey().flatMap(small_star_reduce).distinct().cache()

changes = a.subtract(b).union(b.subtract(a)).collect()

if len(changes) == 0:

break

results = a.collect()

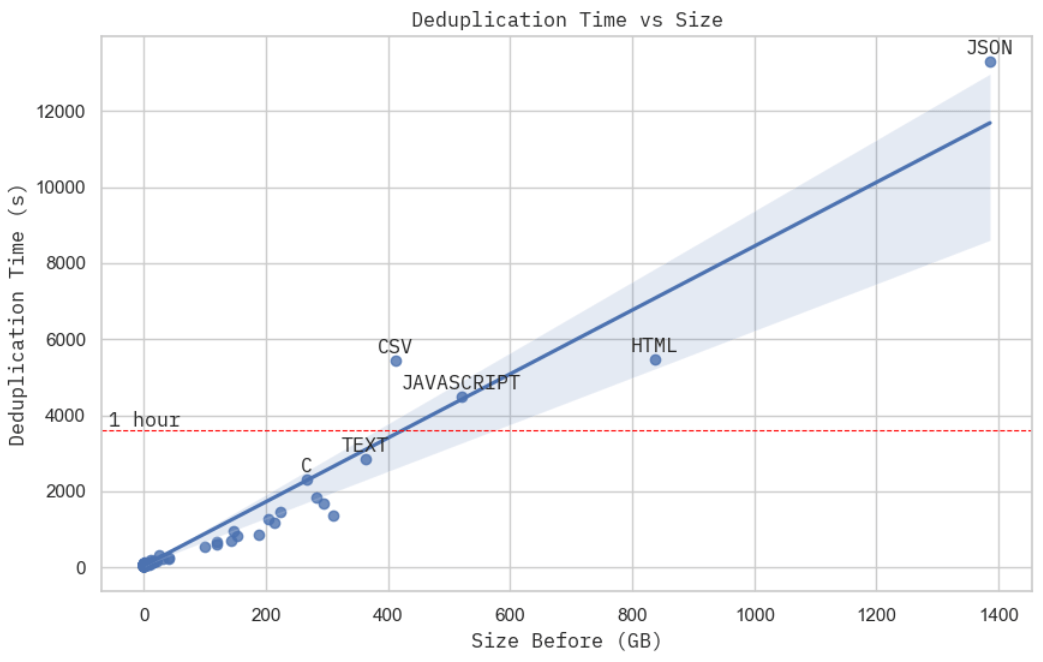

Moreover, due to cloud providers, we will arrange Spark clusters like a breeze with services like GCP DataProc. In the long run, we will comfortably run this system to deduplicate 1.4 TB of knowledge in just below 4 hours with a budget of $15 an hour.

Quality Matters

Scaling a ladder doesn’t get us to the moon. That is why we want to be sure that that is the suitable direction, and we’re using it the suitable way.

Early on, our parameters were largely inherited from the CodeParrot experiments, and our ablation experiment indicated that those settings did improve the model’s downstream performance[16]. We then set to further explore this path and may confirm that[4]:

- Near-deduplication improves the model’s downstream performance with a much smaller dataset (6 TB VS. 3 TB)

- We’ve not found out the limit yet, but a more aggressive deduplication (6 TB VS. 2.4 TB) can improve the performance much more:

- Lower the similarity threshold

- Increase the shingle size (unigram → 5-gram)

- Ditch false positive checking because we will afford to lose a small percentage of false positives

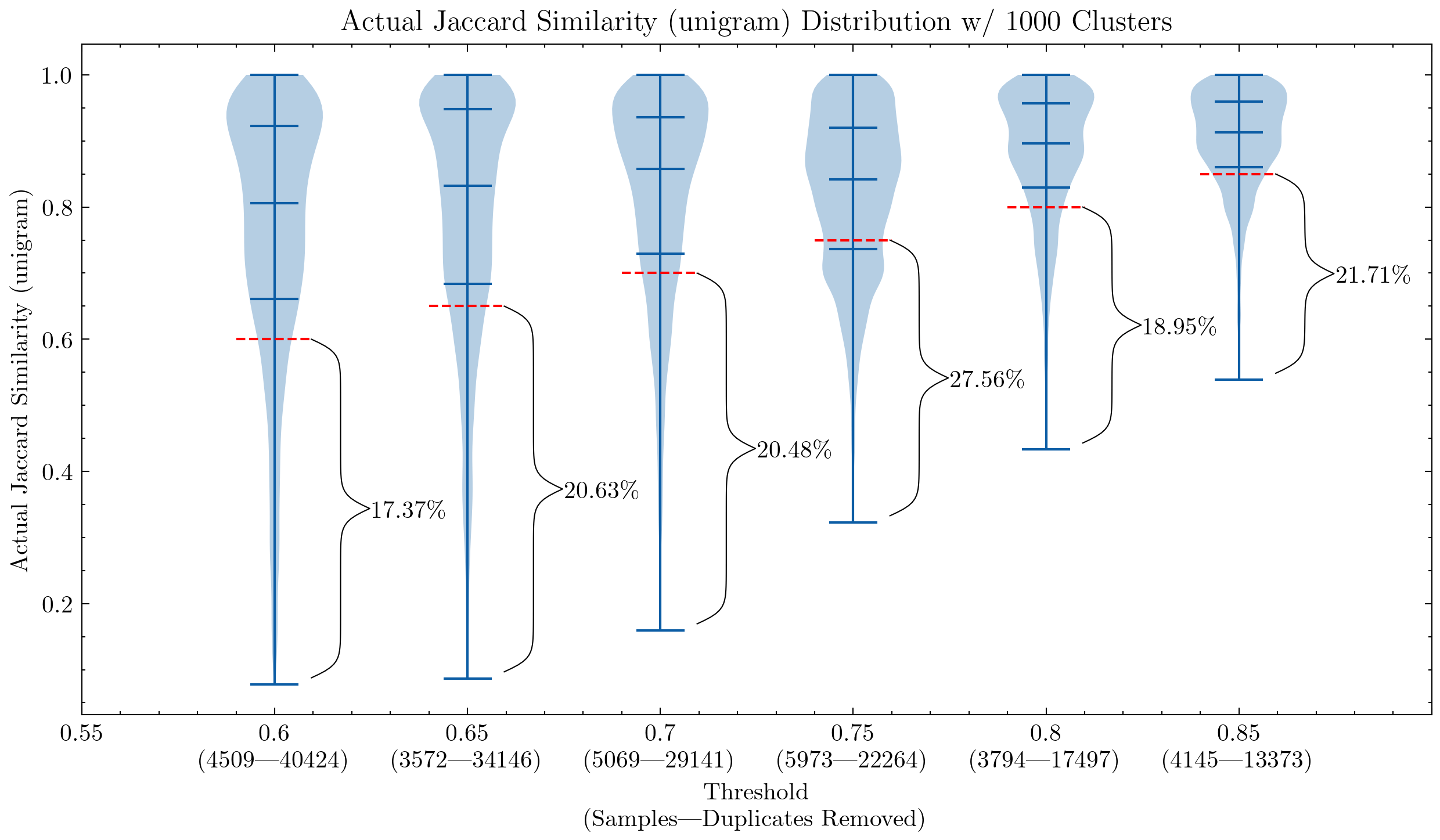

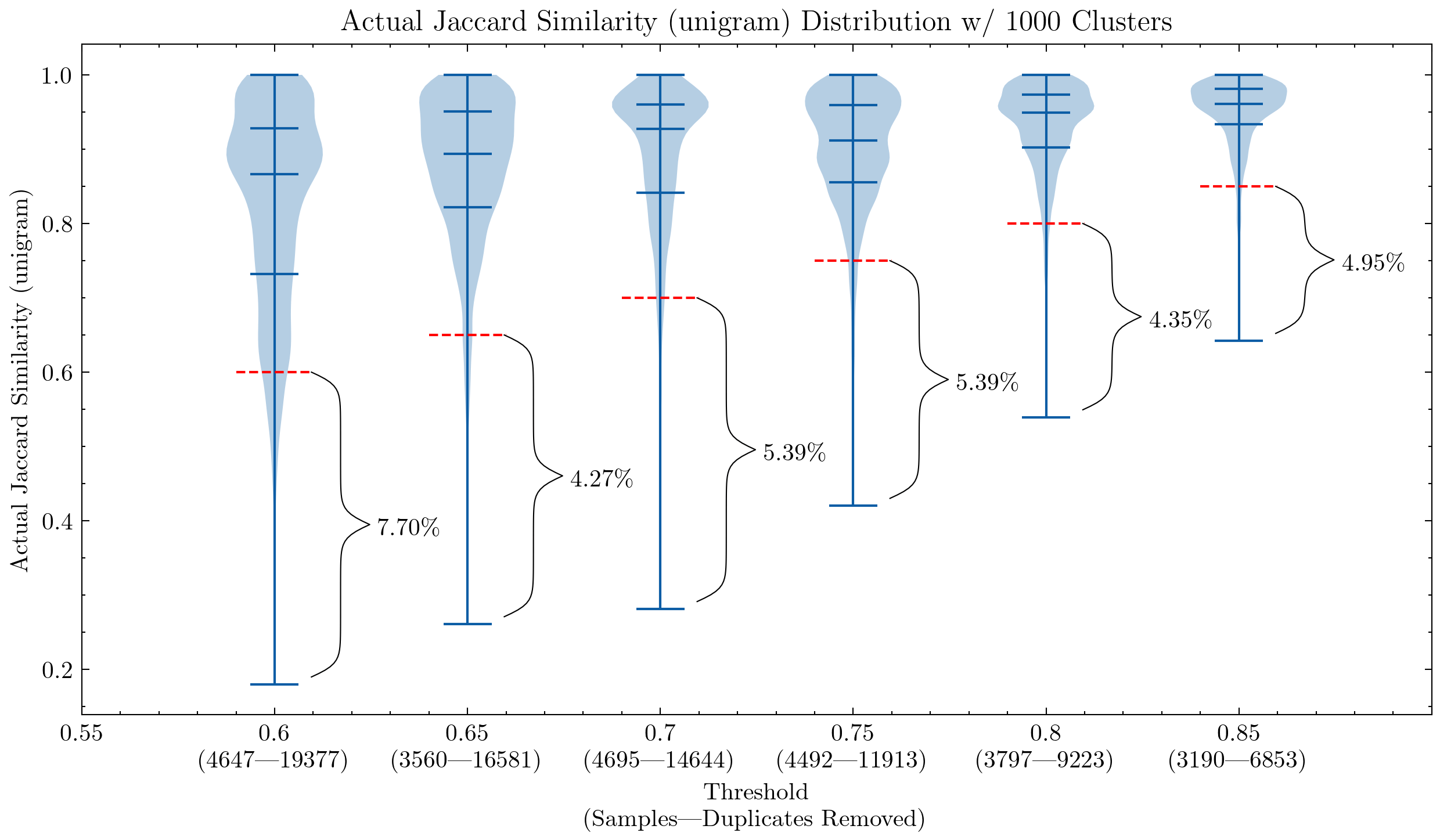

Image: Two graphs showing the impact of similarity threshold and shingle size, the primary one is using unigram and the second 5-gram. The red dash line shows the similarity cutoff: any documents below can be regarded as false positives — their similarities with other documents inside a cluster are lower than the brink.

These graphs might help us understand why it was obligatory to double-check the false positives for CodeParrot and early version of the Stack: using unigram creates many false positives; Additionally they show that by increasing the shingle size to 5-gram, the share of false positives decreases significantly. A smaller threshold is desired if we wish to maintain the deduplication aggressiveness.

Additional experiments also showed that lowering the brink removes more documents which have high similarity pairs, meaning an increased recall within the segment we actually would love to remove essentially the most.

Scaling

This is not essentially the most rigorous scaling proof you could find, however the deduplication time, given a hard and fast computation budget, looks practically linear to the physical size of the dataset. While you take a more in-depth take a look at the cluster resource usage when processing JSON dataset, the biggest subset within the Stack, you may see the MinHash + LSH (stage 2) dominated the whole real computation time (stage 2 + 3), which from our previous evaluation is — linear to the dataset physical volume.

Proceed with Caution

Deduplication doesn’t exempt you from thorough data exploration and evaluation. As well as, these deduplication discoveries hold true for the Stack, however it doesn’t mean it is quickly applicable to other datasets or languages. It’s a very good first step towards constructing a greater dataset, and further investigations similar to data quality filtering (e.g., vulnerability, toxicity, bias, generated templates, PII) are still much needed.

We still encourage you to perform similar evaluation in your datasets before training. For instance, it won’t be very helpful to do deduplication if you might have tight time and compute budget: @geiping_2022 mentions that substring deduplication didn’t improve their model’s downstream performance. Existing datasets may additionally require thorough examination before use, for instance, @gao_2020 states that they only made sure the Pile itself, together with its splits, are deduplicated, they usually won’t proactively deduplicating for any downstream benchmarks and leave that call to readers.

When it comes to data leakage and benchmark contamination, there remains to be much to explore. We needed to retrain our code models because HumanEval was published in one among the GitHub repos in Python. Early near-deduplication results also suggest that MBPP[19], one of the popular benchmarks for coding, shares loads of similarity with many Leetcode problems (e.g., task 601 in MBPP is largely Leetcode 646, task 604 ≃ Leetcode 151.). And everyone knows GitHub isn’t any wanting those coding challenges and solutions. It should be even tougher if someone with bad intentions upload all of the benchmarks in the shape of python scripts, or other less obvious ways, and pollute all of your training data.

Future Directions

- Substring deduplication. Although it showed some advantages for English[3], it just isn’t clear yet if this must be applied to code data as well;

- Repetition: paragraphs which might be repeated multiple times in a single document. @rae_2021 shared some interesting heuristics on the best way to detect and take away them.

- Using model embeddings for semantic deduplication. It’s one other whole research query with scaling, cost, ablation experiments, and trade-off with near-deduplication. There are some intriguing takes on this[20], but we still need more situated evidence to attract a conclusion (e.g, @abbas_2023‘s only text deduplication reference is @lee_2022a, whose important claim is deduplicating helps as a substitute of attempting to be SOTA).

- Optimization. There may be at all times room for optimization: higher quality evaluation, scaling, downstream performance impact evaluation etc.

- Then there may be one other direction to have a look at things: To what extent near-deduplication starts to harm performance? To what extent similarity is required for diversity as a substitute of being regarded as redundancy?

Credits

The banner image incorporates emojis (hugging face, Santa, document, wizard, and wand) from Noto Emoji (Apache 2.0). This blog post is proudly written with none generative APIs.

Huge due to Huu Nguyen @Huu and Hugo Laurençon @HugoLaurencon for the collaboration in BigScience and everybody at BigCode for the assistance along the best way! In the event you ever find any error, be happy to contact me: mouchenghao at gmail dot com.

Supporting Resources

References

- [1] : Nikhil Kandpal, Eric Wallace, Colin Raffel, Deduplicating Training Data Mitigates Privacy Risks in Language Models, 2022

- [2] : Gowthami Somepalli, et al., Diffusion Art or Digital Forgery? Investigating Data Replication in Diffusion Models, 2022

- [3] : Katherine Lee, Daphne Ippolito, et al., Deduplicating Training Data Makes Language Models Higher, 2022

- [4] : Loubna Ben Allal, Raymond Li, et al., SantaCoder: Don’t reach for the celebs!, 2023

- [5] : Leo Gao, Stella Biderman, et al., The Pile: An 800GB Dataset of Diverse Text for Language Modeling, 2020

- [6] : Asier Gutiérrez-Fandiño, Jordi Armengol-Estapé, et al., MarIA: Spanish Language Models, 2022

- [7] : Jack W. Rae, Sebastian Borgeaud, et al., Scaling Language Models: Methods, Evaluation & Insights from Training Gopher, 2021

- [8] : Xi Victoria Lin, Todor Mihaylov, et al., Few-shot Learning with Multilingual Language Models, 2021

- [9] : Hugo Laurençon, Lucile Saulnier, et al., The BigScience ROOTS Corpus: A 1.6TB Composite Multilingual Dataset, 2022

- [10] : Daniel Fried, Armen Aghajanyan, et al., InCoder: A Generative Model for Code Infilling and Synthesis, 2022

- [11] : Erik Nijkamp, Bo Pang, et al., CodeGen: An Open Large Language Model for Code with Multi-Turn Program Synthesis, 2023

- [12] : Yujia Li, David Choi, et al., Competition-Level Code Generation with AlphaCode, 2022

- [13] : Frank F. Xu, Uri Alon, et al., A Systematic Evaluation of Large Language Models of Code, 2022

- [14] : Aakanksha Chowdhery, Sharan Narang, et al., PaLM: Scaling Language Modeling with Pathways, 2022

- [15] : Lewis Tunstall, Leandro von Werra, Thomas Wolf, Natural Language Processing with Transformers, Revised Edition, 2022

- [16] : Denis Kocetkov, Raymond Li, et al., The Stack: 3 TB of permissively licensed source code, 2022

- [17] : Rocky | Project Hail Mary Wiki | Fandom

- [18] : Raimondas Kiveris, Silvio Lattanzi, et al., Connected Components in MapReduce and Beyond, 2014

- [19] : Jacob Austin, Augustus Odena, et al., Program Synthesis with Large Language Models, 2021

- [20]: Amro Abbas, Kushal Tirumala, et al., SemDeDup: Data-efficient learning at web-scale through semantic deduplication, 2023

- [21]: Edith Cohen, MinHash Sketches : A Temporary Survey, 2016