Recent (06/2023): This blog post is strongly inspired by “Superb-tuning XLS-R on Multi-Lingual ASR” and may be seen as an improved version of it.

Wav2Vec2 is a pretrained model for Automatic Speech Recognition (ASR) and was released in September 2020 by Alexei Baevski, Michael Auli, and Alex Conneau. Soon after the strong performance of Wav2Vec2 was demonstrated on probably the most popular English datasets for ASR, called LibriSpeech, Facebook AI presented two multi-lingual versions of Wav2Vec2, called XLSR and XLM-R, able to recognising speech in as much as 128 languages. XLSR stands for cross-lingual speech representations and refers back to the model’s ability to learn speech representations which can be useful across multiple languages.

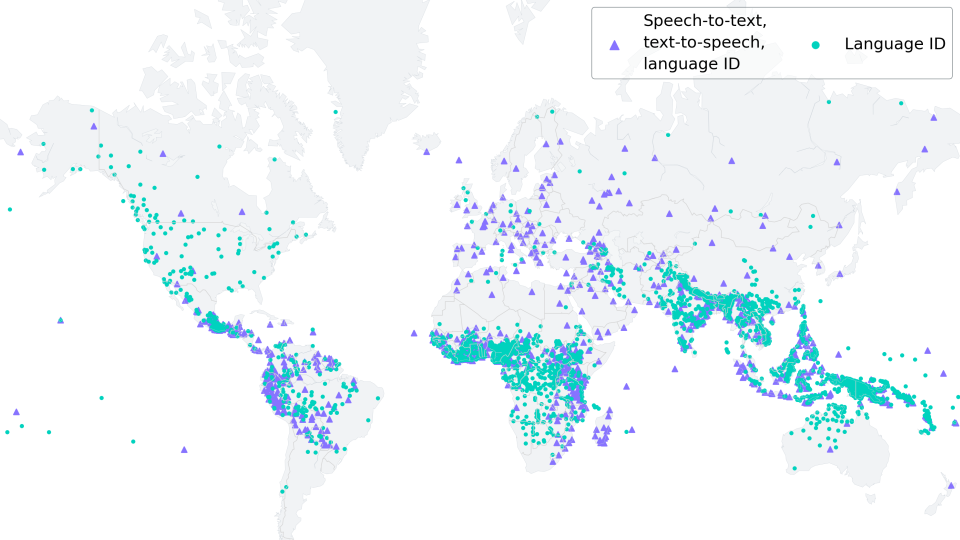

Meta AI’s most up-to-date release, Massive Multilingual Speech (MMS) by Vineel Pratap, Andros Tjandra, Bowen Shi, et al. takes multi-lingual speech representations to a brand new level. Over 1,100 spoken languages may be identified, transcribed and generated with the varied language identification, speech recognition, and text-to-speech checkpoints released.

On this blog post, we show how MMS’s Adapter training achieves astonishingly low word error rates after just 10-20 minutes of fine-tuning.

For low-resource languages, we strongly recommend using MMS’ Adapter training versus fine-tuning the entire model as is completed in “Superb-tuning XLS-R on Multi-Lingual ASR”.

In our experiments, MMS’ Adapter training is each more memory efficient, more robust and yields higher performance for low-resource languages. For medium to high resource languages it will probably still be advantageous to fine-tune the entire checkpoint as a substitute of using Adapter layers though.

Preserving the world’s language diversity

In response to https://www.ethnologue.com/ around 3000, or 40% of all “living” languages, are endangered as a consequence of fewer and fewer native speakers.

This trend will only proceed in an increasingly globalized world.

MMS is able to transcribing many languages that are endangered, resembling Ari or Kaivi. In the long run, MMS can play an important role in keeping languages alive by helping the remaining speakers to create written records and communicate of their native tongue.

To adapt to 1000+ different vocabularies, MMS uses of Adapters – a training method where only a small fraction of model weights are trained.

Adapter layers act like linguistic bridges, enabling the model to leverage knowledge from one language when deciphering one other.

Superb-tuning MMS

MMS unsupervised checkpoints were pre-trained on greater than half 1,000,000 hours of audio in over 1,400 languages, starting from 300 million to 1 billion parameters.

You’ll find the pretrained-only checkpoints on the 🤗 Hub for model sizes of 300 million parameters (300M) and one billion parameters (1B):

Note: If you wish to fine-tune the bottom models, you possibly can accomplish that in the very same way as shown in “Superb-tuning XLS-R on Multi-Lingual ASR”.

Much like BERT’s masked language modeling objective, MMS learns contextualized speech representations by randomly masking feature vectors before passing them to a transformer network during self-supervised pre-training.

For ASR, the pretrained MMS-1B checkpoint was further fine-tuned in a supervised fashion on 1000+ languages with a joint vocabulary output layer. As a final step, the joint vocabulary output layer was thrown away and language-specific adapter layers were kept as a substitute. Each adapter layer accommodates just ~2.5M weights, consisting of small linear projection layers for every attention block in addition to a language-specific vocabulary output layer.

Three MMS checkpoints fine-tuned for speech recognition (ASR) have been released. They include 102, 1107, and 1162 adapter weights respectively (one for every language):

You’ll be able to see that the bottom models are saved (as usual) as a model.safetensors file, but as well as these repositories have many adapter weights stored within the repository, e.g. under the name adapter.fra.safetensors for French.

The Hugging Face docs explain thoroughly how such checkpoints may be used for inference, so on this blog post we are going to as a substitute give attention to learning how we are able to efficiently train highly performant adapter models based on any of the released ASR checkpoints.

Training adaptive weights

In machine learning, adapters are a way used to fine-tune pre-trained models while keeping the unique model parameters unchanged. They do that by inserting small, trainable modules, called adapter layers, between the pre-existing layers of the model, which then adapt the model to a particular task without requiring extensive retraining.

Adapters have an extended history in speech recognition and particularly speaker recognition. In speaker recognition, adapters have been effectively used to tweak pre-existing models to acknowledge individual speaker idiosyncrasies, as highlighted in Gales and Woodland’s (1996) and Miao et al.’s (2014) work. This approach not only greatly reduces computational requirements in comparison with training the total model, but additionally allows for higher and more flexible speaker-specific adjustments.

The work done in MMS leverages this concept of adapters for speech recognition across different languages. A small variety of adapter weights are fine-tuned to understand unique phonetic and grammatical traits of every goal language. Thereby, MMS enables a single large base model (e.g., the mms-1b-all checkpoint) and 1000+ small adapter layers (2.5M weights each for mms-1b-all) to grasp and transcribe multiple languages. This dramatically reduces the computational demand of developing distinct models for every language.

Great! Now that we understood the motivation and theory, let’s look into fine-tuning adapter weights for mms-1b-all 🔥

Notebook Setup

As done previously within the “Superb-tuning XLS-R on Multi-Lingual ASR” blog post, we fine-tune the model on the low resource ASR dataset of Common Voice that accommodates only ca. 4h of validated training data.

Identical to Wav2Vec2 or XLS-R, MMS is fine-tuned using Connectionist Temporal Classification (CTC), which is an algorithm that’s used to coach neural networks for sequence-to-sequence problems, resembling ASR and handwriting recognition.

For more details on the CTC algorithm, I highly recommend reading the well-written blog post Sequence Modeling with CTC (2017) by Awni Hannun.

Before we start, let’s install datasets and transformers. Also, we’d like torchaudio to load audio files and jiwer to judge our fine-tuned model using the word error rate (WER) metric .

%%capture

!pip install --upgrade pip

!pip install datasets

!pip install evaluate

!pip install git+https://github.com/huggingface/transformers.git

!pip install jiwer

!pip install speed up

We strongly suggest to upload your training checkpoints on to the 🤗 Hub while training. The Hub repositories have version control inbuilt, so you possibly can ensure that no model checkpoint is lost during training.

To accomplish that you could have to store your authentication token from the Hugging Face website (join here in the event you have not already!)

from huggingface_hub import notebook_login

notebook_login()

Prepare Data, Tokenizer, Feature Extractor

ASR models transcribe speech to text, which suggests that we each need a feature extractor that processes the speech signal to the model’s input format, e.g. a feature vector, and a tokenizer that processes the model’s output format to text.

In 🤗 Transformers, the MMS model is thus accompanied by each a feature extractor, called Wav2Vec2FeatureExtractor, and a tokenizer, called Wav2Vec2CTCTokenizer.

Let’s start by creating the tokenizer to decode the expected output classes to the output transcription.

Create Wav2Vec2CTCTokenizer

Superb-tuned MMS models, resembling mms-1b-all have already got a tokenizer accompanying the model checkpoint. Nonetheless since we would like to fine-tune the model on specific low-resource data of a certain language, it is suggested to totally remove the tokenizer and vocabulary output layer, and easily create latest ones based on the training data itself.

Wav2Vec2-like models fine-tuned on CTC transcribe an audio file with a single forward pass by first processing the audio input right into a sequence of processed context representations after which using the ultimate vocabulary output layer to categorise each context representation to a personality that represents the transcription.

The output size of this layer corresponds to the variety of tokens within the vocabulary, which we are going to extract from the labeled dataset used for fine-tuning. So in step one, we are going to take a have a look at the chosen dataset of Common Voice and define a vocabulary based on the transcriptions.

For this notebook, we are going to use Common Voice’s 6.1 dataset for Turkish. Turkish corresponds to the language code "tr".

Great, now we are able to use 🤗 Datasets’ easy API to download the information. The dataset name is "mozilla-foundation/common_voice_6_1", the configuration name corresponds to the language code, which is "tr" in our case.

Note: Before with the ability to download the dataset, you could have to access it by logging into your Hugging Face account, happening the dataset repo page and clicking on “Agree and Access repository”

Common Voice has many various splits including invalidated, which refers to data that was not rated as “clean enough” to be considered useful. On this notebook, we are going to only make use of the splits "train", "validation" and "test".

Since the Turkish dataset is so small, we are going to merge each the validation and training data right into a training dataset and only use the test data for validation.

from datasets import load_dataset, load_metric, Audio

common_voice_train = load_dataset("mozilla-foundation/common_voice_6_1", "tr", split="train+validation", use_auth_token=True)

common_voice_test = load_dataset("mozilla-foundation/common_voice_6_1", "tr", split="test", use_auth_token=True)

Many ASR datasets only provide the goal text ('sentence') for every audio array ('audio') and file ('path'). Common Voice actually provides far more details about each audio file, resembling the 'accent', etc. Keeping the notebook as general as possible, we only consider the transcribed text for fine-tuning.

common_voice_train = common_voice_train.remove_columns(["accent", "age", "client_id", "down_votes", "gender", "locale", "segment", "up_votes"])

common_voice_test = common_voice_test.remove_columns(["accent", "age", "client_id", "down_votes", "gender", "locale", "segment", "up_votes"])

Let’s write a brief function to display some random samples of the dataset and run it a few times to get a sense for the transcriptions.

from datasets import ClassLabel

import random

import pandas as pd

from IPython.display import display, HTML

def show_random_elements(dataset, num_examples=10):

assert num_examples <= len(dataset), "Cannot pick more elements than there are within the dataset."

picks = []

for _ in range(num_examples):

pick = random.randint(0, len(dataset)-1)

while pick in picks:

pick = random.randint(0, len(dataset)-1)

picks.append(pick)

df = pd.DataFrame(dataset[picks])

display(HTML(df.to_html()))

show_random_elements(common_voice_train.remove_columns(["path", "audio"]), num_examples=10)

Oylar teker teker elle sayılacak.

Son olaylar endişe seviyesini yükseltti.

Tek bir kart hepsinin kapılarını açıyor.

Blogcular da tam bundan bahsetmek istiyor.

Bu Aralık iki bin onda oldu.

Fiyatın altmış altı milyon avro olduğu bildirildi.

Ardından da silahlı çatışmalar çıktı.

"Romanya'da kurumlar gelir vergisi oranı yüzde on altı."

Bu konuda neden bu kadar az şey söylendiğini açıklayabilir misiniz?

Alright! The transcriptions look fairly clean. Having translated the transcribed sentences, it appears that evidently the language corresponds more to written-out text than noisy dialogue. This is sensible considering that Common Voice is a crowd-sourced read speech corpus.

We will see that the transcriptions contain some special characters, resembling ,.?!;:. With no language model, it is way harder to categorise speech chunks to such special characters because they do not really correspond to a characteristic sound unit. E.g., the letter "s" has a roughly clear sound, whereas the special character "." doesn’t.

Also with a view to understand the meaning of a speech signal, it is normally not crucial to incorporate special characters within the transcription.

Let’s simply remove all characters that do not contribute to the meaning of a word and can’t really be represented by an acoustic sound and normalize the text.

import re

chars_to_remove_regex = '[,?.!-;:"“%‘”�']'

def remove_special_characters(batch):

batch["sentence"] = re.sub(chars_to_remove_regex, '', batch["sentence"]).lower()

return batch

common_voice_train = common_voice_train.map(remove_special_characters)

common_voice_test = common_voice_test.map(remove_special_characters)

Let us take a look at the processed text labels again.

show_random_elements(common_voice_train.remove_columns(["path","audio"]))

i̇kinci tur müzakereler eylül ayında başlayacak

jani ve babası bu düşüncelerinde yalnız değil

onurun gözlerindeki büyü

bandiç oyların yüzde kırk sekiz virgül elli dördünü topladı

bu imkansız

bu konu açık değildir

cinayet kamuoyunu şiddetle sarstı

kentin sokakları iki metre su altında kaldı

muhalefet partileri hükümete karşı ciddi bir mücadele ortaya koyabiliyorlar mı

festivale tüm dünyadan elli film katılıyor

Good! This looks higher. We now have removed most special characters from transcriptions and normalized them to lower-case only.

Before finalizing the pre-processing, it’s all the time advantageous to seek the advice of a native speaker of the goal language to see whether the text may be further simplified.

For this blog post, Merve was kind enough to take a fast look and noted that “hatted” characters – like â – aren’t really used anymore in Turkish and may be replaced by their “un-hatted” equivalent, e.g. a.

Because of this we must always replace a sentence like "yargı sistemi hâlâ sağlıksız" to "yargı sistemi hala sağlıksız".

Let’s write one other short mapping function to further simplify the text labels. Remember – the simpler the text labels, the better it’s for the model to learn to predict those labels.

def replace_hatted_characters(batch):

batch["sentence"] = re.sub('[â]', 'a', batch["sentence"])

batch["sentence"] = re.sub('[î]', 'i', batch["sentence"])

batch["sentence"] = re.sub('[ô]', 'o', batch["sentence"])

batch["sentence"] = re.sub('[û]', 'u', batch["sentence"])

return batch

common_voice_train = common_voice_train.map(replace_hatted_characters)

common_voice_test = common_voice_test.map(replace_hatted_characters)

In CTC, it is not uncommon to categorise speech chunks into letters, so we are going to do the identical here.

Let’s extract all distinct letters of the training and test data and construct our vocabulary from this set of letters.

We write a mapping function that concatenates all transcriptions into one long transcription after which transforms the string right into a set of chars.

It’s important to pass the argument batched=True to the map(...) function in order that the mapping function has access to all transcriptions directly.

def extract_all_chars(batch):

all_text = " ".join(batch["sentence"])

vocab = list(set(all_text))

return {"vocab": [vocab], "all_text": [all_text]}

vocab_train = common_voice_train.map(extract_all_chars, batched=True, batch_size=-1, keep_in_memory=True, remove_columns=common_voice_train.column_names)

vocab_test = common_voice_test.map(extract_all_chars, batched=True, batch_size=-1, keep_in_memory=True, remove_columns=common_voice_test.column_names)

Now, we create the union of all distinct letters within the training dataset and test dataset and convert the resulting list into an enumerated dictionary.

vocab_list = list(set(vocab_train["vocab"][0]) | set(vocab_test["vocab"][0]))

vocab_dict = {v: k for k, v in enumerate(sorted(vocab_list))}

vocab_dict

{' ': 0,

'a': 1,

'b': 2,

'c': 3,

'd': 4,

'e': 5,

'f': 6,

'g': 7,

'h': 8,

'i': 9,

'j': 10,

'k': 11,

'l': 12,

'm': 13,

'n': 14,

'o': 15,

'p': 16,

'q': 17,

'r': 18,

's': 19,

't': 20,

'u': 21,

'v': 22,

'w': 23,

'x': 24,

'y': 25,

'z': 26,

'ç': 27,

'ë': 28,

'ö': 29,

'ü': 30,

'ğ': 31,

'ı': 32,

'ş': 33,

'̇': 34}

Cool, we see that each one letters of the alphabet occur within the dataset (which is just not really surprising) and we also extracted the special characters "" and '. Note that we didn’t exclude those special characters since the model has to learn to predict when a word is finished, otherwise predictions would all the time be a sequence of letters that will make it inconceivable to separate words from one another.

One should all the time take note that pre-processing is a vital step before training your model. E.g., we don’t desire our model to distinguish between a and A simply because we forgot to normalize the information. The difference between a and A doesn’t depend upon the “sound” of the letter in any respect, but more on grammatical rules – e.g. use a capitalized letter at the start of the sentence. So it is wise to remove the difference between capitalized and non-capitalized letters in order that the model has a better time learning to transcribe speech.

To make it clearer that " " has its own token class, we give it a more visible character |. As well as, we also add an “unknown” token in order that the model can later cope with characters not encountered in Common Voice’s training set.

vocab_dict["|"] = vocab_dict[" "]

del vocab_dict[" "]

Finally, we also add a padding token that corresponds to CTC’s “blank token“. The “blank token” is a core component of the CTC algorithm. For more information, please take a have a look at the “Alignment” section here.

vocab_dict["[UNK]"] = len(vocab_dict)

vocab_dict["[PAD]"] = len(vocab_dict)

len(vocab_dict)

37

Cool, now our vocabulary is complete and consists of 37 tokens, which suggests that the linear layer that we are going to add on top of the pretrained MMS checkpoint as a part of the adapter weights may have an output dimension of 37.

Since a single MMS checkpoint can provide customized weights for multiple languages, the tokenizer may also consist of multiple vocabularies. Due to this fact, we’d like to nest our vocab_dict to potentially add more languages to the vocabulary in the long run. The dictionary needs to be nested with the name that’s used for the adapter weights and that’s saved within the tokenizer config under the name target_lang.

Let’s use the ISO-639-3 language codes like the unique mms-1b-all checkpoint.

target_lang = "tur"

Let’s define an empty dictionary to which we are able to append the just created vocabulary

new_vocab_dict = {target_lang: vocab_dict}

Note: In case you wish to use this notebook so as to add a brand new adapter layer to an existing model repo ensure to not create an empty, latest vocab dict, but as a substitute re-use one which already exists. To accomplish that you must uncomment the next cells and replace "patrickvonplaten/wav2vec2-large-mms-1b-turkish-colab" with a model repo id to which you wish to add your adapter weights.

Let’s now save the vocabulary as a json file.

import json

with open('vocab.json', 'w') as vocab_file:

json.dump(new_vocab_dict, vocab_file)

In a final step, we use the json file to load the vocabulary into an instance of the Wav2Vec2CTCTokenizer class.

from transformers import Wav2Vec2CTCTokenizer

tokenizer = Wav2Vec2CTCTokenizer.from_pretrained("./", unk_token="[UNK]", pad_token="[PAD]", word_delimiter_token="|", target_lang=target_lang)

If one desires to re-use the just created tokenizer with the fine-tuned model of this notebook, it’s strongly advised to upload the tokenizer to the 🤗 Hub. Let’s call the repo to which we are going to upload the files

"wav2vec2-large-mms-1b-turkish-colab":

repo_name = "wav2vec2-large-mms-1b-turkish-colab"

and upload the tokenizer to the 🤗 Hub.

tokenizer.push_to_hub(repo_name)

CommitInfo(commit_url='https://huggingface.co/patrickvonplaten/wav2vec2-large-mms-1b-turkish-colab/commit/48cccbfd6059aa6ce655e9d94b8358ba39536cb7', commit_message='Upload tokenizer', commit_description='', oid='48cccbfd6059aa6ce655e9d94b8358ba39536cb7', pr_url=None, pr_revision=None, pr_num=None)

Great, you possibly can see the just created repository under https://huggingface.co/

Create Wav2Vec2FeatureExtractor

Speech is a continuous signal and to be treated by computers, it first must be discretized, which is normally called sampling. The sampling rate hereby plays a very important role in that it defines what number of data points of the speech signal are measured per second. Due to this fact, sampling with a better sampling rate ends in a greater approximation of the real speech signal but additionally necessitates more values per second.

A pretrained checkpoint expects its input data to have been sampled roughly from the identical distribution as the information it was trained on. The identical speech signals sampled at two different rates have a really different distribution, e.g., doubling the sampling rate ends in twice as many data points. Thus,

before fine-tuning a pretrained checkpoint of an ASR model, it’s crucial to confirm that the sampling rate of the information that was used to pretrain the model matches the sampling rate of the dataset used to fine-tune the model.

A Wav2Vec2FeatureExtractor object requires the next parameters to be instantiated:

feature_size: Speech models take a sequence of feature vectors as an input. While the length of this sequence obviously varies, the feature size mustn’t. Within the case of Wav2Vec2, the feature size is 1 since the model was trained on the raw speech signal .sampling_rate: The sampling rate at which the model is trained on.padding_value: For batched inference, shorter inputs should be padded with a particular valuedo_normalize: Whether the input needs to be zero-mean-unit-variance normalized or not. Often, speech models perform higher when normalizing the inputreturn_attention_mask: Whether the model should make use of anattention_maskfor batched inference. Typically, XLS-R models checkpoints should all the time use theattention_mask.

from transformers import Wav2Vec2FeatureExtractor

feature_extractor = Wav2Vec2FeatureExtractor(feature_size=1, sampling_rate=16000, padding_value=0.0, do_normalize=True, return_attention_mask=True)

Great, MMS’s feature extraction pipeline is thereby fully defined!

For improved user-friendliness, the feature extractor and tokenizer are wrapped right into a single Wav2Vec2Processor class in order that one only needs a model and processor object.

from transformers import Wav2Vec2Processor

processor = Wav2Vec2Processor(feature_extractor=feature_extractor, tokenizer=tokenizer)

Next, we are able to prepare the dataset.

Preprocess Data

Thus far, we have now not checked out the actual values of the speech signal but just the transcription. Along with sentence, our datasets include two more column names path and audio. path states absolutely the path of the audio file and audio represent already loaded audio data. MMS expects the input within the format of a 1-dimensional array of 16 kHz. Because of this the audio file must be loaded and resampled.

Thankfully, datasets does this robotically when the column name is audio. Let’s try it out.

common_voice_train[0]["audio"]

{'path': '/root/.cache/huggingface/datasets/downloads/extracted/71ba9bd154da9d8c769b736301417178729d2b87b9e00cda59f6450f742ed778/cv-corpus-6.1-2020-12-11/tr/clips/common_voice_tr_17346025.mp3',

'array': array([ 0.00000000e+00, -2.98378618e-13, -1.59835903e-13, ...,

-2.01663317e-12, -1.87991593e-12, -1.17969588e-12]),

'sampling_rate': 48000}

In the instance above we are able to see that the audio data is loaded with a sampling rate of 48kHz whereas the model expects 16kHz, as we saw. We will set the audio feature to the proper sampling rate by making use of cast_column:

common_voice_train = common_voice_train.cast_column("audio", Audio(sampling_rate=16_000))

common_voice_test = common_voice_test.cast_column("audio", Audio(sampling_rate=16_000))

Let’s take a have a look at "audio" again.

common_voice_train[0]["audio"]

{'path': '/root/.cache/huggingface/datasets/downloads/extracted/71ba9bd154da9d8c769b736301417178729d2b87b9e00cda59f6450f742ed778/cv-corpus-6.1-2020-12-11/tr/clips/common_voice_tr_17346025.mp3',

'array': array([ 9.09494702e-13, -6.13908924e-12, -1.09139364e-11, ...,

1.81898940e-12, 4.54747351e-13, 3.63797881e-12]),

'sampling_rate': 16000}

This looked as if it would have worked! Let’s do a final check that the information is appropriately prepared, by printing the form of the speech input, its transcription, and the corresponding sampling rate.

rand_int = random.randint(0, len(common_voice_train)-1)

print("Goal text:", common_voice_train[rand_int]["sentence"])

print("Input array shape:", common_voice_train[rand_int]["audio"]["array"].shape)

print("Sampling rate:", common_voice_train[rand_int]["audio"]["sampling_rate"])

Goal text: bağış anlaşması bir ağustosta imzalandı

Input array shape: (70656,)

Sampling rate: 16000

Good! Every part looks nice – the information is a 1-dimensional array, the sampling rate all the time corresponds to 16kHz, and the goal text is normalized.

Finally, we are able to leverage Wav2Vec2Processor to process the information to the format expected by Wav2Vec2ForCTC for training. To accomplish that let’s make use of Dataset’s map(...) function.

First, we load and resample the audio data, just by calling batch["audio"].

Second, we extract the input_values from the loaded audio file. In our case, the Wav2Vec2Processor only normalizes the information. For other speech models, nonetheless, this step can include more complex feature extraction, resembling Log-Mel feature extraction.

Third, we encode the transcriptions to label ids.

Note: This mapping function is a superb example of how the Wav2Vec2Processor class needs to be used. In “normal” context, calling processor(...) is redirected to Wav2Vec2FeatureExtractor‘s call method. When wrapping the processor into the as_target_processor context, nonetheless, the identical method is redirected to Wav2Vec2CTCTokenizer‘s call method.

For more information please check the docs.

def prepare_dataset(batch):

audio = batch["audio"]

batch["input_values"] = processor(audio["array"], sampling_rate=audio["sampling_rate"]).input_values[0]

batch["input_length"] = len(batch["input_values"])

batch["labels"] = processor(text=batch["sentence"]).input_ids

return batch

Let’s apply the information preparation function to all examples.

common_voice_train = common_voice_train.map(prepare_dataset, remove_columns=common_voice_train.column_names)

common_voice_test = common_voice_test.map(prepare_dataset, remove_columns=common_voice_test.column_names)

Note: datasets robotically takes care of audio loading and resampling. When you want to implement your personal costumized data loading/sampling, be at liberty to simply make use of the "path" column as a substitute and disrespect the "audio" column.

Awesome, now we’re ready to start out training!

Training

The info is processed in order that we’re ready to start out organising the training pipeline. We’ll make use of 🤗’s Trainer for which we essentially must do the next:

-

Define an information collator. In contrast to most NLP models, MMS has a much larger input length than output length. E.g., a sample of input length 50000 has an output length of not more than 100. Given the big input sizes, it’s far more efficient to pad the training batches dynamically meaning that each one training samples should only be padded to the longest sample of their batch and never the general longest sample. Due to this fact, fine-tuning MMS requires a special padding data collator, which we are going to define below

-

Evaluation metric. During training, the model needs to be evaluated on the word error rate. We must always define a

compute_metricsfunction accordingly -

Load a pretrained checkpoint. We’d like to load a pretrained checkpoint and configure it appropriately for training.

-

Define the training configuration.

After having fine-tuned the model, we are going to appropriately evaluate it on the test data and confirm that it has indeed learned to appropriately transcribe speech.

Set-up Trainer

Let’s start by defining the information collator. The code for the information collator was copied from this instance.

Without going into too many details, in contrast to the common data collators, this data collator treats the input_values and labels in a different way and thus applies two separate padding functions on them (again making use of MMS processor’s context manager). That is crucial because, in speech recognition, input and output are of various modalities so that they mustn’t be treated by the identical padding function.

Analogous to the common data collators, the padding tokens within the labels with -100 in order that those tokens are not taken into consideration when computing the loss.

import torch

from dataclasses import dataclass, field

from typing import Any, Dict, List, Optional, Union

@dataclass

class DataCollatorCTCWithPadding:

"""

Data collator that may dynamically pad the inputs received.

Args:

processor (:class:`~transformers.Wav2Vec2Processor`)

The processor used for proccessing the information.

padding (:obj:`bool`, :obj:`str` or :class:`~transformers.tokenization_utils_base.PaddingStrategy`, `optional`, defaults to :obj:`True`):

Select a technique to pad the returned sequences (in accordance with the model's padding side and padding index)

amongst:

* :obj:`True` or :obj:`'longest'`: Pad to the longest sequence within the batch (or no padding if only a single

sequence if provided).

* :obj:`'max_length'`: Pad to a maximum length specified with the argument :obj:`max_length` or to the

maximum acceptable input length for the model if that argument is just not provided.

* :obj:`False` or :obj:`'do_not_pad'` (default): No padding (i.e., can output a batch with sequences of

different lengths).

"""

processor: Wav2Vec2Processor

padding: Union[bool, str] = True

def __call__(self, features: List[Dict[str, Union[List[int], torch.Tensor]]]) -> Dict[str, torch.Tensor]:

input_features = [{"input_values": feature["input_values"]} for feature in features]

label_features = [{"input_ids": feature["labels"]} for feature in features]

batch = self.processor.pad(

input_features,

padding=self.padding,

return_tensors="pt",

)

labels_batch = self.processor.pad(

labels=label_features,

padding=self.padding,

return_tensors="pt",

)

labels = labels_batch["input_ids"].masked_fill(labels_batch.attention_mask.ne(1), -100)

batch["labels"] = labels

return batch

data_collator = DataCollatorCTCWithPadding(processor=processor, padding=True)

Next, the evaluation metric is defined. As mentioned earlier, the

predominant metric in ASR is the word error rate (WER), hence we are going to use it on this notebook as well.

from evaluate import load

wer_metric = load("wer")

The model will return a sequence of logit vectors:

with and .

A logit vector accommodates the log-odds for every word within the vocabulary we defined earlier, thus config.vocab_size. We’re fascinated by the almost certainly prediction of the model and thus take the argmax(...) of the logits. Also, we transform the encoded labels back to the unique string by replacing -100 with the pad_token_id and decoding the ids while ensuring that consecutive tokens are not grouped to the identical token in CTC style .

def compute_metrics(pred):

pred_logits = pred.predictions

pred_ids = np.argmax(pred_logits, axis=-1)

pred.label_ids[pred.label_ids == -100] = processor.tokenizer.pad_token_id

pred_str = processor.batch_decode(pred_ids)

label_str = processor.batch_decode(pred.label_ids, group_tokens=False)

wer = wer_metric.compute(predictions=pred_str, references=label_str)

return {"wer": wer}

Now, we are able to load the pretrained checkpoint of mms-1b-all. The tokenizer’s pad_token_id should be to define the model’s pad_token_id or within the case of Wav2Vec2ForCTC also CTC’s blank token .

Since, we’re only training a small subset of weights, the model is just not susceptible to overfitting. Due to this fact, we ensure to disable all dropout layers.

Note: When using this notebook to coach MMS on one other language of Common Voice those hyper-parameter settings may not work thoroughly. Be at liberty to adapt those depending in your use case.

from transformers import Wav2Vec2ForCTC

model = Wav2Vec2ForCTC.from_pretrained(

"facebook/mms-1b-all",

attention_dropout=0.0,

hidden_dropout=0.0,

feat_proj_dropout=0.0,

layerdrop=0.0,

ctc_loss_reduction="mean",

pad_token_id=processor.tokenizer.pad_token_id,

vocab_size=len(processor.tokenizer),

ignore_mismatched_sizes=True,

)

Some weights of Wav2Vec2ForCTC weren't initialized from the model checkpoint at facebook/mms-1b-all and are newly initialized since the shapes didn't match:

- lm_head.bias: found shape torch.Size([154]) in the checkpoint and torch.Size([39]) in the model instantiated

- lm_head.weight: found shape torch.Size([154, 1280]) in the checkpoint and torch.Size([39, 1280]) in the model instantiated

You need to probably TRAIN this model on a down-stream task to have the ability to make use of it for predictions and inference.

Note: It is anticipated that some weights are newly initialized. Those weights correspond to the newly initialized vocabulary output layer.

We now wish to ensure that only the adapter weights might be trained and that the remainder of the model stays frozen.

First, we re-initialize all of the adapter weights which may be done with the handy init_adapter_layers method. It’s also possible to not re-initilize the adapter weights and proceed fine-tuning, but on this case one should ensure to load fitting adapter weights via the load_adapter(...) method before training. Often the vocabulary still is not going to match the custom training data thoroughly though, so it’s always easier to simply re-initialize all adapter layers in order that they may be easily fine-tuned.

model.init_adapter_layers()

Next, we freeze all weights, but the adapter layers.

model.freeze_base_model()

adapter_weights = model._get_adapters()

for param in adapter_weights.values():

param.requires_grad = True

In a final step, we define all parameters related to training.

To provide more explanation on a few of the parameters:

group_by_lengthmakes training more efficient by grouping training samples of comparable input length into one batch. This will significantly speed up training time by heavily reducing the general variety of useless padding tokens which can be passed through the modellearning_ratewas chosen to be 1e-3 which is a standard default value for training with Adam. Other learning rates might work equally well.

For more explanations on other parameters, one can take a have a look at the docs.

To avoid wasting GPU memory, we enable PyTorch’s gradient checkpointing and likewise set the loss reduction to “mean“.

MMS adapter fine-tuning converges extremely fast to superb performance, so even for a dataset as small as 4h we are going to only train for 4 epochs.

During training, a checkpoint might be uploaded asynchronously to the hub every 200 training steps. It lets you also mess around with the demo widget even while your model continues to be training.

Note: If one doesn’t wish to upload the model checkpoints to the hub, simply set push_to_hub=False.

from transformers import TrainingArguments

training_args = TrainingArguments(

output_dir=repo_name,

group_by_length=True,

per_device_train_batch_size=32,

evaluation_strategy="steps",

num_train_epochs=4,

gradient_checkpointing=True,

fp16=True,

save_steps=200,

eval_steps=100,

logging_steps=100,

learning_rate=1e-3,

warmup_steps=100,

save_total_limit=2,

push_to_hub=True,

)

Now, all instances may be passed to Trainer and we’re ready to start out training!

from transformers import Trainer

trainer = Trainer(

model=model,

data_collator=data_collator,

args=training_args,

compute_metrics=compute_metrics,

train_dataset=common_voice_train,

eval_dataset=common_voice_test,

tokenizer=processor.feature_extractor,

)

To permit models to develop into independent of the speaker rate, in CTC, consecutive tokens which can be similar are simply grouped as a single token. Nonetheless, the encoded labels mustn’t be grouped when decoding since they do not correspond to the expected tokens of the model, which is why the group_tokens=False parameter must be passed. If we would not pass this parameter a word like "hello" would incorrectly be encoded, and decoded as "helo".

The blank token allows the model to predict a word, resembling "hello" by forcing it to insert the blank token between the 2 l’s. A CTC-conform prediction of "hello" of our model could be [PAD] [PAD] "h" "e" "e" "l" "l" [PAD] "l" "o" "o" [PAD].

Training

Training should take lower than half-hour depending on the GPU used.

trainer.train()

| Training Loss | Training Steps | Validation Loss | Wer |

|---|---|---|---|

| 4.905 | 100 | 0.215 | 0.280 |

| 0.290 | 200 | 0.167 | 0.232 |

| 0.2659 | 300 | 0.161 | 0.229 |

| 0.2398 | 400 | 0.156 | 0.223 |

The training loss and validation WER go down nicely.

We see that fine-tuning adapter layers of mms-1b-all for just 100 steps outperforms fine-tuning the entire xls-r-300m checkpoint shown here already by a big margin.

From the official paper and this quick comparison it becomes clear that mms-1b-all has a much higher capability of transfering knowledge to a low-resource language and needs to be preferred over xls-r-300m. As well as, training can also be more memory-efficient as only a small subset of layers are trained.

The adapter weights might be uploaded as a part of the model checkpoint, but we also wish to ensure to save lots of them individually in order that they will easily be off- and onloaded.

Let’s save all of the adapter layers into the training output dir in order that it will probably be appropriately uploaded to the Hub.

from safetensors.torch import save_file as safe_save_file

from transformers.models.wav2vec2.modeling_wav2vec2 import WAV2VEC2_ADAPTER_SAFE_FILE

import os

adapter_file = WAV2VEC2_ADAPTER_SAFE_FILE.format(target_lang)

adapter_file = os.path.join(training_args.output_dir, adapter_file)

safe_save_file(model._get_adapters(), adapter_file, metadata={"format": "pt"})

Finally, you possibly can upload the results of the training to the 🤗 Hub.

trainer.push_to_hub()

One in all the principal benefits of adapter weights training is that the “base” model which makes up roughly 99% of the model weights is kept unchanged and only a small 2.5M adapter checkpoint must be shared with a view to use the trained checkpoint.

This makes it very simple to coach additional adapter layers and add them to your repository.

You’ll be able to accomplish that very easily by simply re-running this script and changing the language you want to to coach on to a unique one, e.g. swe for Swedish. As well as, you must ensure that the vocabulary doesn’t get completely overwritten but that the brand new language vocabulary is appended to the present one as stated above within the commented out cells.

To reveal how different adapter layers may be loaded, I actually have trained and uploaded also an adapter layer for Swedish under the iso language code swe as you possibly can see here

You’ll be able to load the fine-tuned checkpoint as usual by utilizing from_pretrained(...), but you must ensure to also add a target_lang=" to the tactic in order that the proper adapter is loaded. You need to also set the goal language appropriately in your tokenizer.

Let’s examine how we are able to load the Turkish checkpoint first.

model_id = "patrickvonplaten/wav2vec2-large-mms-1b-turkish-colab"

model = Wav2Vec2ForCTC.from_pretrained(model_id, target_lang="tur").to("cuda")

processor = Wav2Vec2Processor.from_pretrained(model_id)

processor.tokenizer.set_target_lang("tur")

Let’s check that the model can appropriately transcribe Turkish

from datasets import Audio

common_voice_test_tr = load_dataset("mozilla-foundation/common_voice_6_1", "tr", data_dir="./cv-corpus-6.1-2020-12-11", split="test", use_auth_token=True)

common_voice_test_tr = common_voice_test_tr.cast_column("audio", Audio(sampling_rate=16_000))

Let’s process the audio, run a forward pass and predict the ids

input_dict = processor(common_voice_test_tr[0]["audio"]["array"], sampling_rate=16_000, return_tensors="pt", padding=True)

logits = model(input_dict.input_values.to("cuda")).logits

pred_ids = torch.argmax(logits, dim=-1)[0]

Finally, we are able to decode the instance.

print("Prediction:")

print(processor.decode(pred_ids))

print("nReference:")

print(common_voice_test_tr[0]["sentence"].lower())

Output:

Prediction:

pekçoğuda roman toplumundan geliyor

Reference:

pek çoğu da roman toplumundan geliyor.

This looks prefer it’s almost exactly right, just two empty spaces must have been added in the primary word.

Now it is rather easy to vary the adapter to Swedish by calling model.load_adapter(...) and by changing the tokenizer to Swedish as well.

model.load_adapter("swe")

processor.tokenizer.set_target_lang("swe")

We again load the Swedish test set from common voice

common_voice_test_swe = load_dataset("mozilla-foundation/common_voice_6_1", "sv-SE", data_dir="./cv-corpus-6.1-2020-12-11", split="test", use_auth_token=True)

common_voice_test_swe = common_voice_test_swe.cast_column("audio", Audio(sampling_rate=16_000))

and transcribe a sample:

input_dict = processor(common_voice_test_swe[0]["audio"]["array"], sampling_rate=16_000, return_tensors="pt", padding=True)

logits = model(input_dict.input_values.to("cuda")).logits

pred_ids = torch.argmax(logits, dim=-1)[0]

print("Prediction:")

print(processor.decode(pred_ids))

print("nReference:")

print(common_voice_test_swe[0]["sentence"].lower())

Output:

Prediction:

jag lämnade grovjobbet åt honom

Reference:

jag lämnade grovjobbet åt honom.

Great, this looks like an ideal transcription!

We have shown on this blog post how MMS Adapter Weights fine-tuning not only gives state-of-the-art performance on low-resource languages, but additionally significantly accelerates training time and allows to simply construct a set of customized adapter weights.

Related posts and extra links are listed here: