TLDR: Infini-attention’s performance gets worse as we increase the variety of times we compress the memory, and to the very best of our knowledge, ring attention, YaRN and rope scaling are still the very best ways for extending a pretrained model to longer context length.

Section 0: Introduction

The context length of language models is certainly one of the central attributes besides the model’s performance. For the reason that emergence of in-context learning, adding relevant information to the model’s input has grow to be increasingly essential. Thus, the context length rapidly increased from paragraphs (512 tokens with BERT/GPT-1) to pages (1024/2048 with GPT-2 and GPT-3 respectively) to books (128k of Claude) all of the method to collections of books (1-10M tokens of Gemini). Nonetheless, extending standard attention to such length stays difficult.

A small intro to Ring Attention: Ring Attention was first introduced by researchers from UC Berkeley in 2024 https://huggingface.co/blog/infini-attention (to the very best of our knowledge). This engineering technique helps overcome memory limitations by performing self-attention and feedforward network computations in a blockwise fashion and distributing sequence dimensions across multiple devices, allowing concurrent computation and communication.

Even with Ring Attention, the variety of GPUs required to coach a Llama 3 8B on a 1-million-token context length with a batch size of 1 is 512 GPUs. As scaling laws have shown, there’s a robust correlation between model size and its downstream performance, which implies the larger the model, the higher (after all, each models must be well-trained). So we not only desire a 1m context length, but we would like a 1m context length on the most important model (e.g., Llama 3 8B 405B). And there are only a couple of corporations in existence which have the resources to accomplish that.

Recap on the memory complexity of self-attention

In standard attention (not-flash-attention), every token attends to each other token within the sequence, leading to an attention matrix of size [seq_len, seq_len]. For every pair of tokens, we compute an attention rating, and because the sequence length (seq_len) increases, the memory and computation requirements grow quadratically: Memory for the eye matrix is O(seq_len^2). As an illustration, a 10x increase in sequence length leads to a 100x increase in memory requirements. Even memory efficient attention methods like Flash Attention still increase linearly with context length and are bottlenecked by single GPU memory, resulting in a typical max context far lower than 1M tokens on today’s GPUs.

Motivated by this, we explore another approach to plain attention: infini-attention. The paper was released by researchers from Google in April 2024 https://huggingface.co/blog/infini-attention. As a substitute of computing attention scores between every word, Infini-attention divides the sequence into segments, compresses earlier segments into a hard and fast buffer, and allows the subsequent segment to retrieve memory from the sooner segments while limiting attention scores to words throughout the current segment. A key advantage is its fixed buffer size upper bounds the whole memory usage. It also uses the identical query inside a segment to access information from each its own segment and the compressed memory, which enables us to cheaply extend the context length for a pretrained model. In theory, we will achieve infinite context length, because it only keeps a single buffer for all of the memory of earlier segments. Nonetheless, in point of fact compression limits the quantity of knowledge which might effectively been stored and the query is thus: how usably is the memory such compressed?

While understanding a brand new method on paper is comparatively easy, actually making it work is usually an entire other story, story which may be very rarely shared publicly. Motivated by this, we decided to share our experiments and chronicles in reproducing the Infini-attention paper, what motivated us throughout the debugging process (we spent 90% of our time debugging a convergence issue), and the way hard it may possibly be to make these items work.

With the discharge of Llama 3 8B (which has a context length limit of 8k tokens), we sought to increase this length to 1 million tokens without quadratically increasing the memory. On this blog post, we are going to start by explaining how Infini-attention works. We’ll then outline our reproduction principles and describe our initial small-scale experiment. We discuss the challenges we faced, how we addressed them, and conclude with a summary of our findings and other ideas we explored. In case you’re keen on testing our trained checkpoint https://huggingface.co/blog/infini-attention, you could find it in the next repo https://huggingface.co/blog/infini-attention (note that we currently provide the code as is).

Section 1: Reproduction Principles

We found the next rules helpful when implementing a brand new method and use it as guiding principles for a number of our work:

- Principle 1: Start with the smallest model size that gives good signals, and scale up the experiments when you get good signals.

- Principle 2. All the time train a solid baseline to measure progress.

- Principle 3. To find out if a modification improves performance, train two models identically apart from the modification being tested.

With these principles in mind, let’s dive into how Infini-attention actually works. Understanding the mechanics might be crucial as we move forward with our experiments.

Section 2: How does Infini-attention works

-

Step 1: Split the input sequence into smaller, fixed-size chunks called “segments”.

-

Step 2: Calculate the usual causal dot-product attention inside each segment.

-

Step 3: Pull relevant information from the compressive memory using the present segment’s query vector. The retrieval process is defined mathematically as follows:

- : The retrieved content from memory, representing the long-term context.

- : The query matrix, where is the variety of queries, and is the dimension of every query.

- : The memory matrix from the previous segment, storing key-value pairs.

- : A nonlinear activation function, specifically element-wise Exponential Linear Unit (ELU) plus 1.

- : A normalization term.

import torch.nn.functional as F

from torch import einsum

from einops import rearrange

def _retrieve_from_memory(query_states, prev_memory, prev_normalization):

...

sigma_query_states = F.elu(query_states) + 1

retrieved_memory = einsum(

sigma_query_states,

prev_memory,

"batch_size n_heads seq_len d_k, batch_size n_heads d_k d_v -> batch_size n_heads seq_len d_v",

)

denominator = einsum(

sigma_query_states,

prev_normalization,

"batch_size n_heads seq_len d_head, batch_size n_heads d_head -> batch_size n_heads seq_len",

)

denominator = rearrange(

denominator,

"batch_size n_heads seq_len -> batch_size n_heads seq_len 1",

)

retrieved_memory = retrieved_memory / denominator

return retrieved_memory

-

Step 4: Mix the local context (from the present segment) with the long-term context (retrieved from the compressive memory) to generate the ultimate output. This manner, each short-term and long-term contexts might be considered in the eye output.

- : The combined attention output.

- : A learnable scalar parameter that controls the trade-off between the long-term memory content and the local context.

- : The eye output from the present segment using dot-product attention.

-

Step 5: Update the compressive memory by adding the key-value states from the present segment, so this permits us to build up the context over time.

- : The updated memory matrix for the present segment, incorporating recent information.

- : The important thing matrix for the present segment, representing the brand new keys to be stored.

- : The worth matrix for the present segment, representing the brand new values related to the keys.

- : The -th key vector in the important thing matrix.

- : The updated normalization term for the present segment.

import torch

def _update_memory(prev_memory, prev_normalization, key_states, value_states):

...

sigma_key_states = F.elu(key_states) + 1

if prev_memory is None or prev_normalization is None:

new_value_states = value_states

else:

numerator = einsum(

sigma_key_states,

prev_memory,

"batch_size n_heads seq_len d_k, batch_size n_heads d_k d_v -> batch_size n_heads seq_len d_v",

)

denominator = einsum(

sigma_key_states,

prev_normalization,

"batch_size n_heads seq_len d_k, batch_size n_heads d_k -> batch_size n_heads seq_len",

)

denominator = rearrange(

denominator,

"batch_size n_heads seq_len -> batch_size n_heads seq_len 1",

)

prev_v = numerator / denominator

new_value_states = value_states - prev_v

memory = torch.matmul(sigma_key_states.transpose(-2, -1), new_value_states)

normalization = reduce(

sigma_key_states,

"batch_size n_heads seq_len d_head -> batch_size n_heads d_head",

reduction="sum",

...

)

memory += prev_memory if prev_memory is not None else 0

normalization += prev_normalization if prev_normalization is not None else 0

return memory, normalization

- Step 6: As we move from one segment to the subsequent, we discard the previous segment’s attention states and pass along the updated compressed memory to the subsequent segment.

def forward(...):

...

outputs = []

global_weights = F.sigmoid(self.balance_factors)

...

local_weights = 1 - global_weights

memory = None

normalization = None

for segment_hidden_state, segment_sequence_mask in zip(segment_hidden_states, segment_sequence_masks):

attn_outputs = self.forward_with_hidden_states(

hidden_states=segment_hidden_state, sequence_mask=segment_sequence_mask, return_qkv_states=True

)

local_attn_outputs = attn_outputs["attention_output"]

query_states, key_states, value_states = attn_outputs["qkv_states_without_pe"]

q_bs = query_states.shape[0]

q_length = query_states.shape[2]

...

retrieved_memory = _retrieve_from_memory(

query_states, prev_memory=memory, prev_normalization=normalization

)

attention_output = global_weights * retrieved_memory + local_weights * local_attn_outputs

...

output = o_proj(attention_output)

memory, normalization = _update_memory(memory, normalization, key_states, value_states)

outputs.append(output)

outputs = torch.cat(outputs, dim=1)

...

Now that we have a handle on the speculation, time to roll up our sleeves and get into some actual experiments. Let’s start small for quick feedback and iterate rapidly.

Section 3: First experiments on a small scale

Llama 3 8B is sort of large so we decided to begin with a 200M Llama, pretraining Infini-attention from scratch using Nanotron https://huggingface.co/blog/infini-attention and the Fineweb dataset https://huggingface.co/blog/infini-attention. Once we obtained good results with the 200M model, we proceeded with continual pretraining on Llama 3 8B. We used a batch size of two million tokens, a context length of 256, gradient clipping of 1, and weight decay of 0.1, the primary 5,000 iterations were a linear warmup, while the remaining steps were cosine decay, with a learning rate of 3e-5.

Evaluating using the passkey retrieval task

The passkey retrieval task was first introduced by researchers from EPFL https://huggingface.co/blog/infini-attention. It is a task designed to judge a model’s ability to retrieve information from long contexts where the placement of the knowledge is controllable. The input format for prompting a model is structured as follows:

There is very important info hidden inside a number of irrelevant text. Find it and memorize them. I'll quiz you in regards to the essential information there. The grass is green. The sky is blue. The sun is yellow. Here we go. There and back again. (repeat x times) The pass key's 9054. Remember it. 9054 is the pass key. The grass is green. The sky is blue. The sun is yellow. Here we go. There and back again. (repeat y times) What's the pass key? The pass key's

We consider the model successful at this task if its output incorporates the “needle” (“9054” within the above case) and unsuccessful if it doesn’t. In our experiments, we place the needle at various positions throughout the context, specifically at 0%, 5%, 10%, …, 95%, and 100% of the whole context length (with 0% being the furthest away from the generated tokens). As an illustration, if the context length is 1024 tokens, placing the needle at 10% means it’s positioned across the 102nd token. At each depth position, we test the model with 10 different samples and calculate the mean success rate.

First results

Listed below are some first results on the small 200M model:

As you may see it somewhat works. In case you have a look at the sample generations, you may see that Infini-attention generates content related to the sooner segment.

Since Infini-attention predicts the primary token within the second segment by conditioning on all the content of the primary segment, which it generated as “_grad” for the primary token, this provides a superb signal. To validate whether this signal is a false positive, we hypothesize that Infini-attention generates content related to its earlier segment because when given “_grad” as the primary generated token of the second segment, it consistently generates PyTorch-related tutorials, which occur to relate to its earlier segment. Subsequently, we conducted a sanity test where the one input token was “_grad”, and it generated [text here]. This implies it does use the memory, but just doesn’t use it well enough (to retrieve the precise needle or proceed the precise content of its earlier segment). The generation:

_graduate_education.html

Graduate Education

The Department of Physics and Astronomy offers a program resulting in the Master of Science degree in physics. This system is designed to supply students with a broad background in

Based on these results, the model appears to actually use the compressed memory. We decided to scale up our experiments by continually pretraining a Llama 3 8B. Unfortunately, the model did not pass the needle evaluation when the needle was placed in an earlier segment.

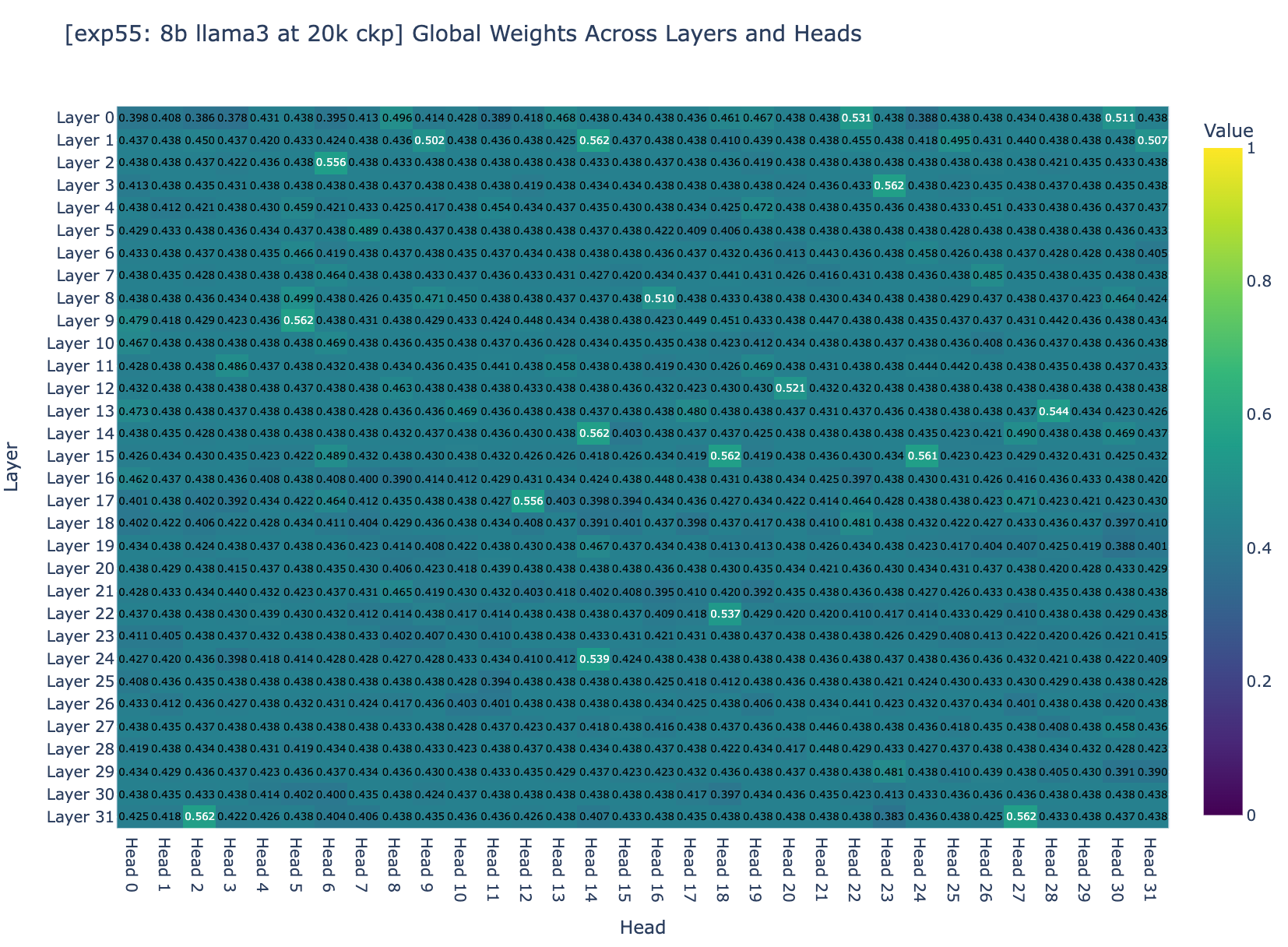

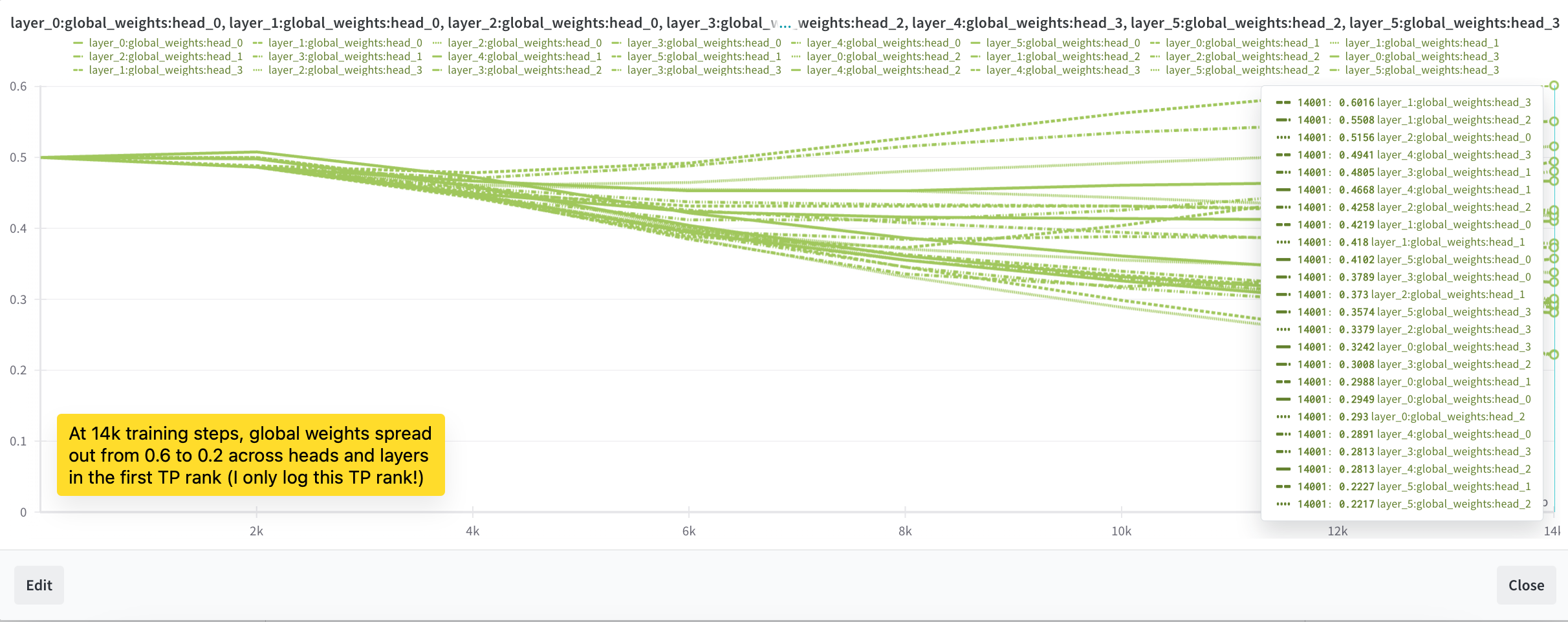

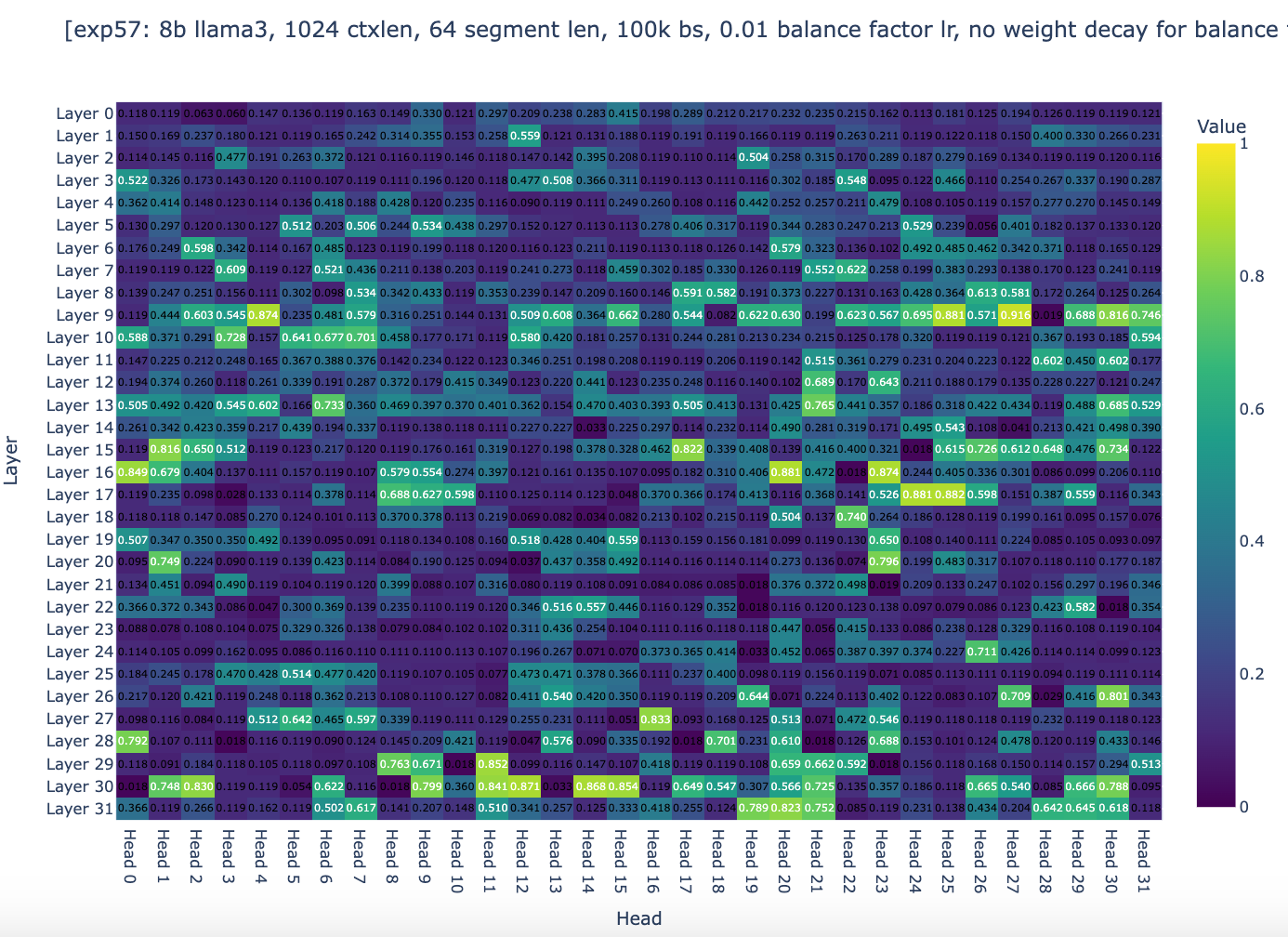

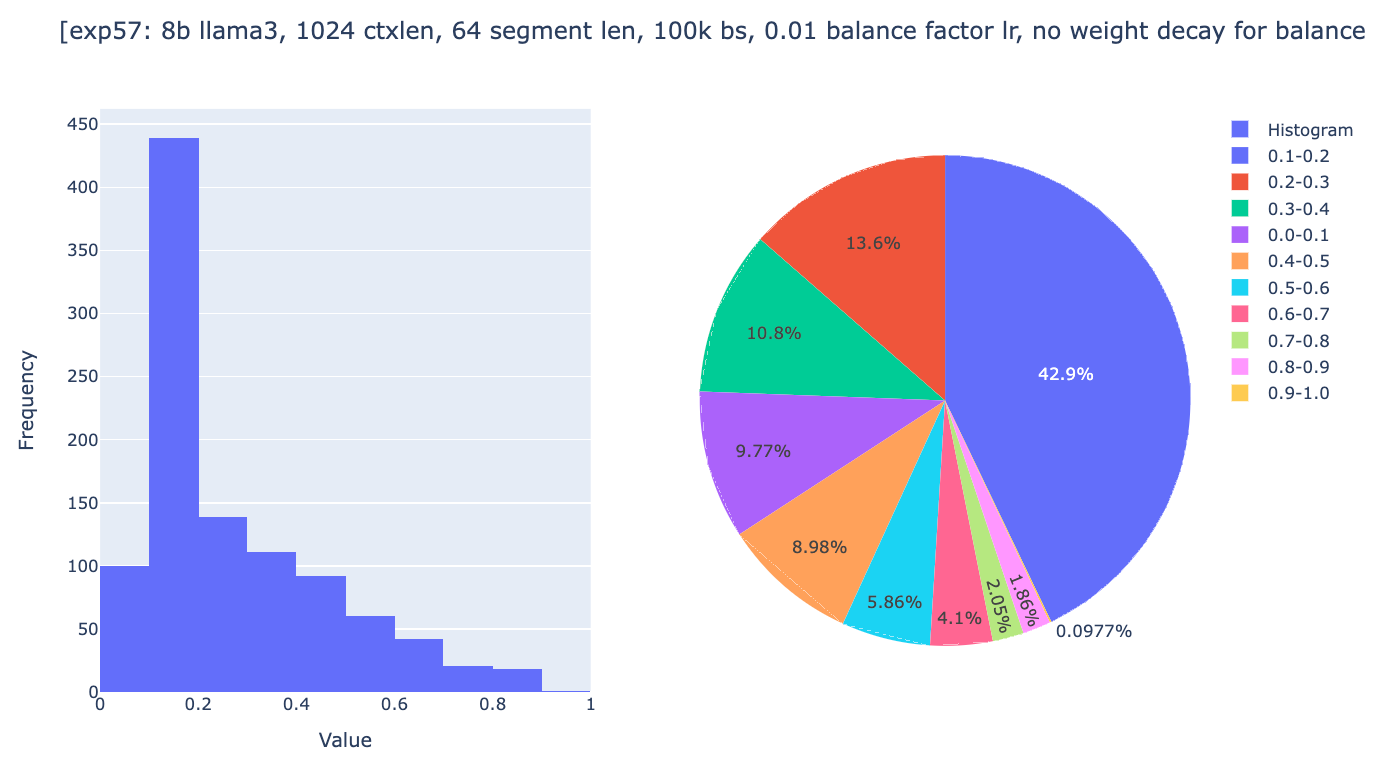

We decided to examine the balance aspects (factor balancing the quantity of compressed and not-compressed memory) across all layers. Based on Figure 3a and Figure 3b, we found that about 95% of the weights are centered around 0.5. Recall that for a weight to converge to an excellent range, it relies on two general aspects: the step size and the magnitude of the gradients. Nonetheless, Adam normalizes the gradients to a magnitude of 1 so the query became: are the training hyper-parameters the precise ones to permit the finetuning to converge?

Section 4: Studying convergence?

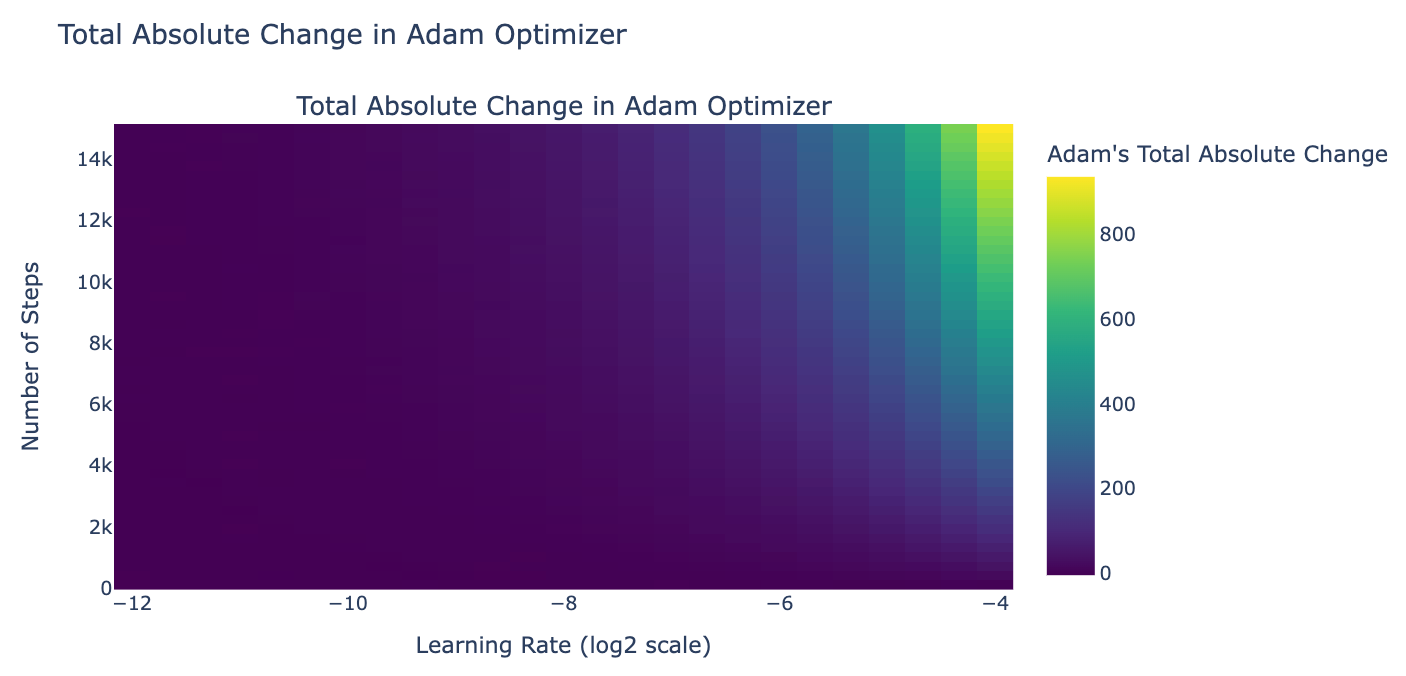

We decided to simulate how much balance weights would change during training given gradients are in a superb range (L2 norm is 0.01), and located that, given the config of the last 8B LLaMA3 fine-tuning experiment, the whole of absolute changes in the burden can be 0.03. Since we initialize balance aspects at 0 (it doesn’t matter on this case), the weights at the top can be within the range [0 – 0.03, 0 + 0.03] = [-0.03, 0.03].

An informed guess for infinity attention to work well is when global weights opened up within the range 0 and 1 as within the paper. Given the burden above, sigmoid([-0.03, 0.03]) = tensor([0.4992, 0.5008]) (this matches with our previous experiment results that the balance factor is ~0.5). We decided as next step to make use of a better learning rate for balance aspects (and all other parameters use Llama 3 8B’s learning rate), and a bigger number of coaching steps to permit the balance aspects to vary by a minimum of 4, in order that we allow global weights to succeed in the best weights if gradient descent wants (sigmoid(-4) ≈ 0, sigmoid(4) ≈ 1).

We also note that for the reason that gradients don’t all the time go in the identical direction, cancellations occur. This implies we must always aim for a learning rate and training steps which can be significantly larger than the whole absolute changes. Recall that the training rate for Llama 3 8B is 3.0×10^-4, which implies if we use this as a world learning rate, the gating cannot converge by any means.

Conclusion: we decided to go together with a world learning rate of 3.0×10^-4 and a gating learning rate of 0.01 which should allows the gating function to converge.

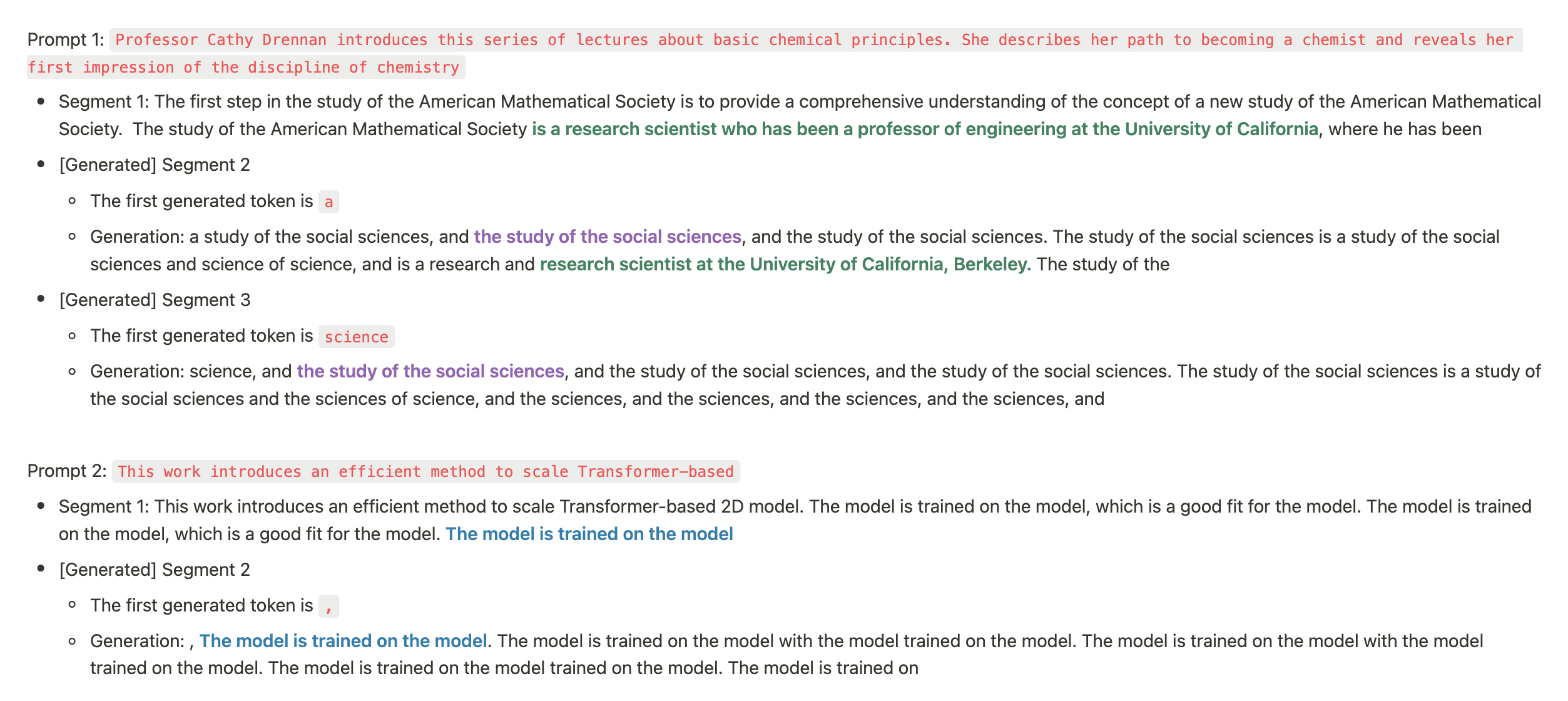

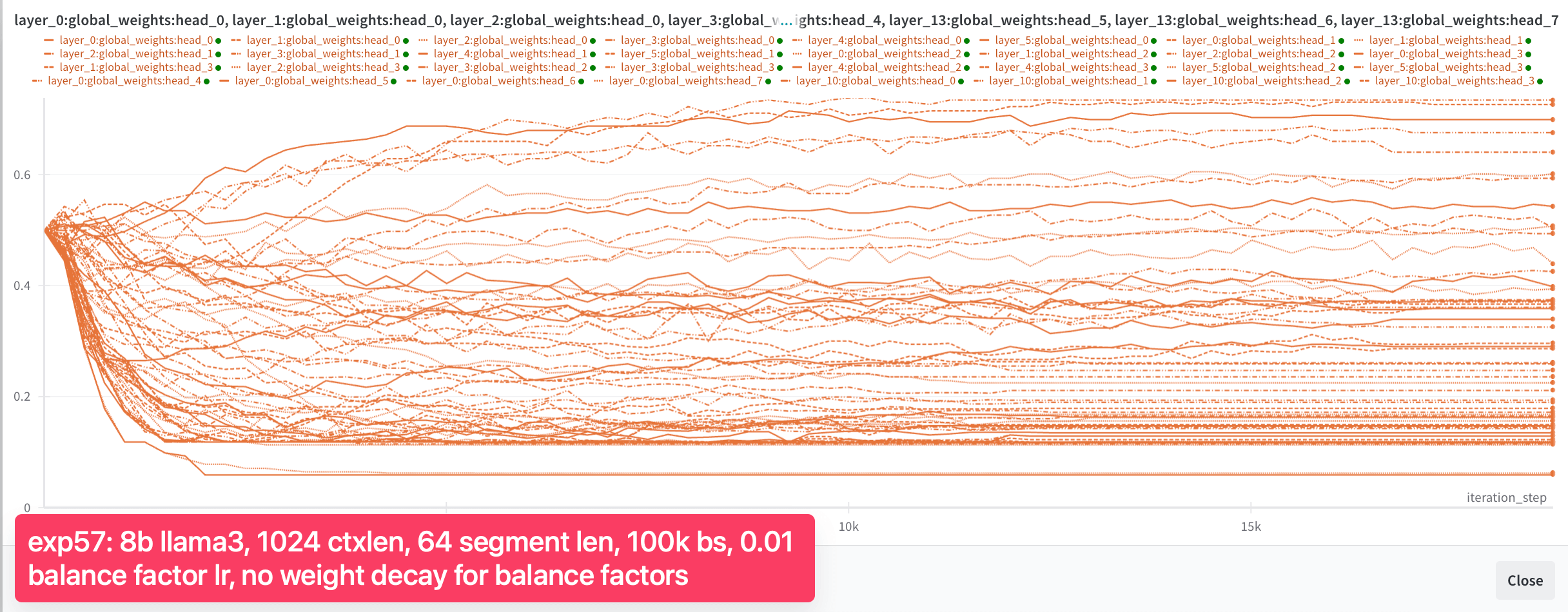

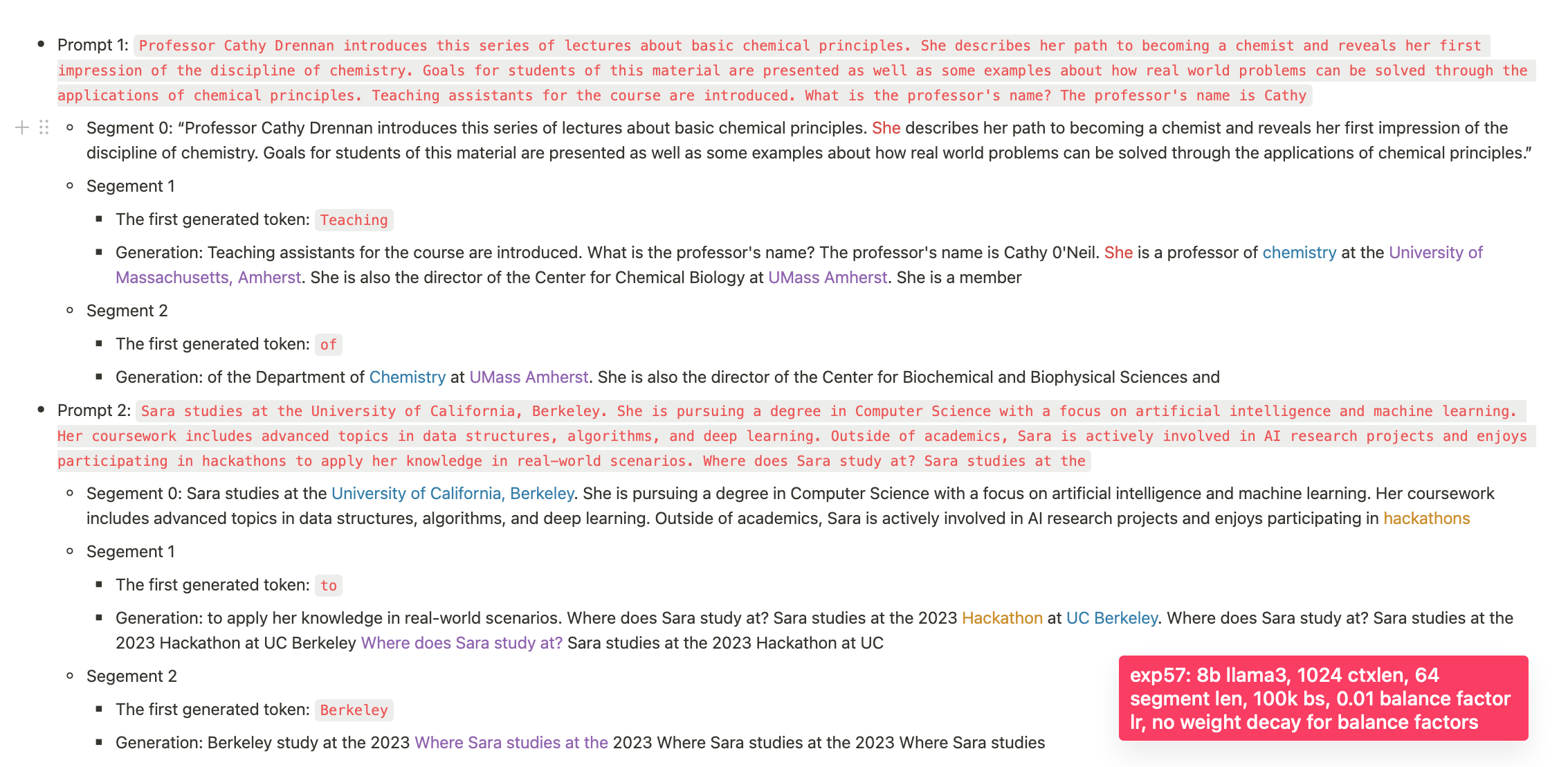

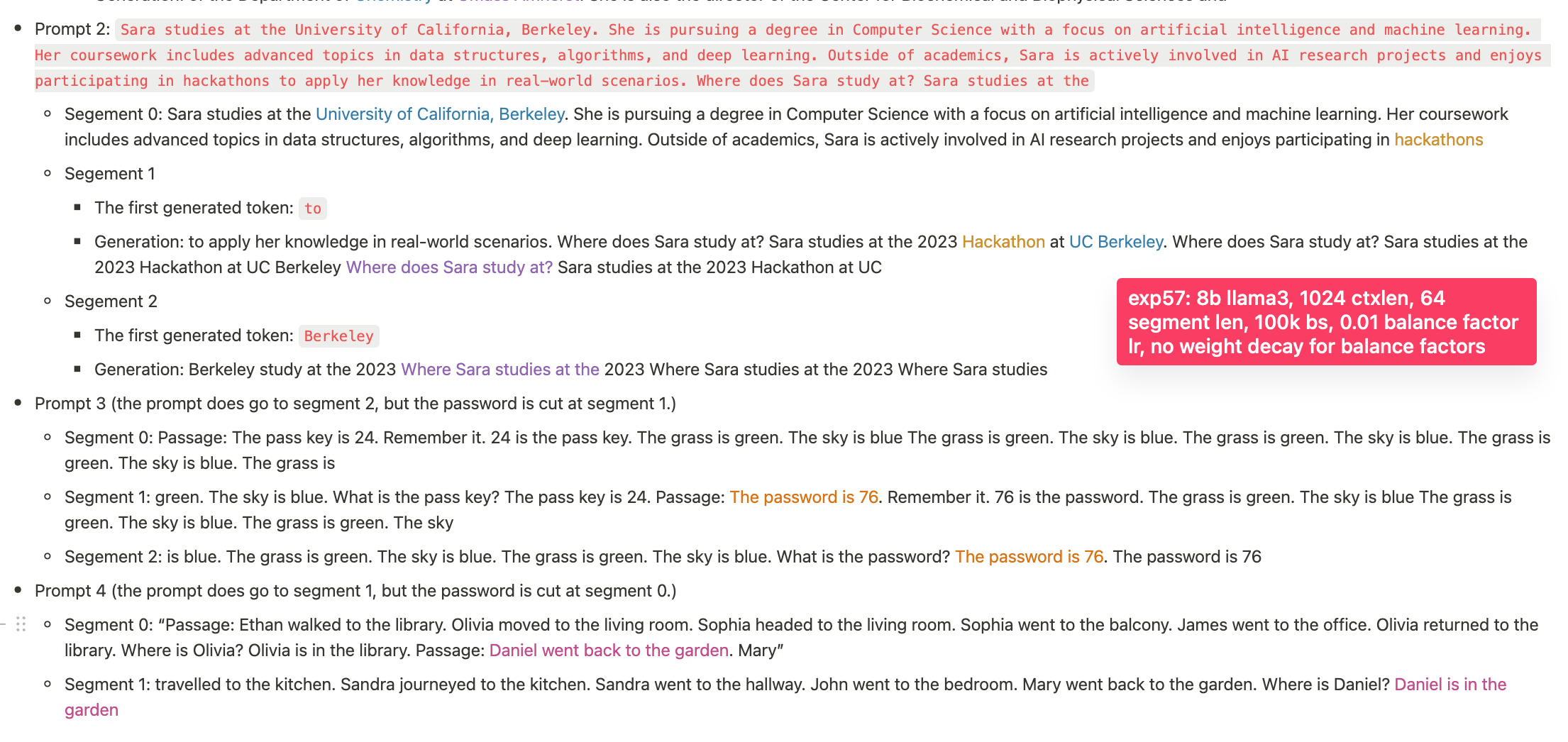

With these hyper-parameters the balance aspects in Infini-attention are trainable, but we observed that the 200M llama’s loss went NaN after 20B tokens (we tried learning rates from 0.001 to 1.0e-6). We investigated a couple of generations on the 20B tokens checkpoint (10k training steps) which you’ll see in Figure 4a. The model now proceed the precise content and recall identities (if the memory is knocked out, it generates trash).

Nevertheless it continues to be not capable of recall the needle from one segment to the opposite (it does so reliably throughout the segment). Needle evaluation fails completely when the needle is placed within the 1st segment (100% success when placed within the 2nd segment, out of two segments total). As showed in Figure 4b, we also observed that the balance aspects stopped changing after 5,000 steps. While we made some progress, we weren’t yet out of the woods. The balance aspects were still not behaving as we hoped. We decided to dig deeper and make more adjustments.

Section 5: No weight decay on balance aspects

Inspecting intimately the balance factor once more, we saw some progress: roughly 95% of the heads now show a world weight starting from 0.4 to 0.5, and not one of the heads have a world weight greater than 0.6. However the weights still aren’t in the best range.

We considered one other potential reason: weight decay, which inspires a small L2 norm of balance aspects, leading sigmoid values to converge near zero and factor to focus on 0.5.

Yet one more potential reason could possibly be that we used too small a rollout. Within the 200m experiment, we only used 4 rollouts, and within the 8b experiment, we only used 2 rollouts (8192**2). Using a bigger rollout should incentive the model to compress and use the memory well. So we decided to extend the variety of rollouts to 16 and use no weight decay. We scaled down the context length to 1024 context length, with 16 rollouts, getting segment lengths of 64.

As you may see, global weights at the moment are distributed across the range from 0 to 1, with 10% of heads having a world weight between 0.9 and 1.0, though after 18k steps, most heads stopped changing their global weights. We were then quite confident that the experiments were setup to permit convergence if the spirits of gradient descent are with us. The one query remaining was whether the final approach of Infini-attention could works well enough.

The next evaluations were run at 1.5B tokens.

- 0-short: Within the prompt 2, it recalls where an individual studies (the 8b model yesterday failed at this), but fails on the needle passkey (not comprehensively run yet; will run).

- 1-short

- Prompt 3: It identifies where an individual locates.

- Prompt 4: It passes the needle pass key

And on this cases, the models proceed generating the precise content of earlier segments. (In our previous experiments, the model did not proceed with the precise content of an earlier segment and only generated something roughly related; the brand new model is thus quite a lot better already.)

Section 6: Conclusion

Unfortunately, despite these progress, we found that Infini-attention was not convincing enough in our experiments and specifically not reliable enough. At this stage of our reproduction we’re still of the opinion that Ring Attention https://huggingface.co/blog/infini-attention, YaRN https://huggingface.co/blog/infini-attention and cord scaling https://huggingface.co/blog/infini-attention are higher options for extending a pretrained model to longer context length.

These later technics still include large resource requirements for very large model sizes (e.g., 400B and beyond). we thus till think that exploring compression techniques or continuing to push the series of experiments we have bee describing on this blog post is of great interest for the community and are are excited to follow and take a look at recent techniques which may be developped and overcome a number of the limitation of the current work.

Recaps

- What it means to coach a neural network: give it good data, arrange the architecture and training to receive good gradient signals, and permit it to converge.

- Infini-attention’s long context performance decreases because the variety of times we compresses the memory.

- Gating is very important; tweaking the training to permit the gating to converge improves Infini-attention’s long context performance (but not adequate).

- All the time train a superb reference model as a baseline to measure progress.

- There’s one other bug that messes up the scale in the eye output, leading to a situation where, though the loss decreases throughout training, the model still cannot generate coherent text inside its segment length. Lesson learned: Even when you condition the model poorly, gradient descent can still discover a method to decrease the loss. Nonetheless, the model won’t work as expected, so all the time run evaluations.

Acknowledgements

Because of Leandro von Werra and Thomas Wolf for his or her guidance on the project, and to Tsendsuren Munkhdalai for sharing additional details on the unique experiments. We also appreciate Leandro’s feedback on the blog post and are grateful to Hugging Face’s science cluster for the compute.