You’ve optimized your model. Your pipeline is running easily. But now, your cloud bill has skyrocketed. Running 1B+ classifications or embeddings per day isn’t only a technical challenge—it’s a financial one. How do you process at this scale without blowing your budget? Whether you are running large-scale document classification or bulk embedding pipelines for Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG), you wish cost-efficient, high-throughput inference to make it feasible, and also you get that from having a well optimized configuration.

These tasks often use encoder models, that are much smaller than modern LLMs, but on the 1B+ inference request scale it’s still quite a non-trivial task. Simply to be clear, that is English Wikipedia 144x over. I haven’t seen much information on how you can approach this with cost in mind and I need to tackle that. This blog breaks down HOW to calculate cost and latency for giant scale classification and embedding. We’ll analyze different model architectures, benchmark costs across hardware decisions, and provide you with a transparent framework for optimizing your individual setup. Moreover we must always give you the chance to construct some intuition in case you do not feel like going through the method yourself.

You may have a pair questions:

- What’s the most affordable configuration to unravel my task for 1B inputs? (Batch Inference)

- How can I try this while also considering latency? (Heavy Usage)

Here is the code to make it occur: https://github.com/datavistics/encoder-analysis

tl;I’m not gonna reproduce this, tell me what you found;dr

With this pricing I used to be capable of get this cost:

Approach

To judge cost and latency we want 4 key components:

- Hardware options: A wide range of hardware to match costs

- Deployment Facilitator: A technique to deploy models with settings of our alternative

- Load Testing: A way of sending requests and measuring the performance

- Inference Server: A technique to run the model efficiently on the hardware of alternative

I’ll be leveraging Inference Endpoints for my Hardware Options, because it allows me to pick from a wide selection of hardware decisions. Do note you may replace that along with your GPUs of alternative/consideration. For the Deployment Facilitator I will be using the ever so useful Hugging Face Hub Library which allows me to programmatically deploy models easily.

For the Inference Server I’ll even be using Infinity which is a tremendous library for serving encoder based models (and more now!). I’ve already written about TEI, which is one other amazing library. You need to definitely consider TEI when approaching your use-case, though this blog focuses on methodology reasonably than framework comparisons. Infinity has quite a few key strengths, like serving multimodal embeddings, targeting different hardware (AMD, Nvidia, CPU and Inferentia) and running any latest models that contain distant code which have not been integrated into huggingface’s transformer library. A very powerful of those to me is that the majority models are compatible by default.

For Load Testing I will be using k6 from Grafana which is an open-source load testing tool written in go together with a javascript interface. It’s easily configurable, has high performance, and has low overhead. It has a variety of built-in executors which are super useful. It also pre-allocates Virtual Users (VUs), which might be rather more realistic than throwing some testing together yourself.

I’ll undergo 3 use-cases that ought to cover a wide range of interesting points:

Optimization

Optimization is a difficult issue, as there’s loads to contemplate. At a high level, I need to comb across vital load testing parameters and find what works best for a single GPU, as most encoder models will slot in a single GPU. Once we’ve a baseline of cost for a single GPU, the variety of GPUs and throughput might be scaled horizontally by increasing the variety of replica GPUs.

Setup

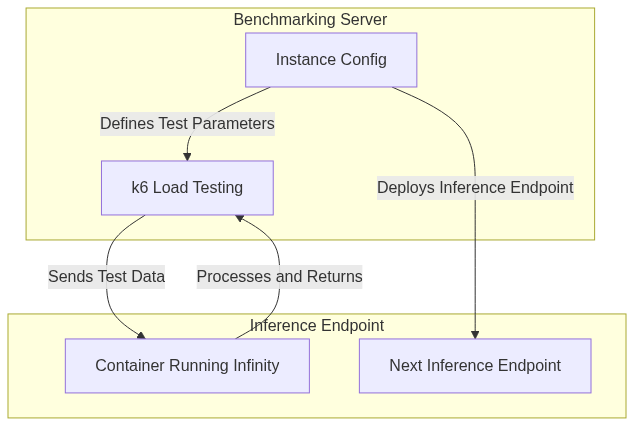

For every use-case that is the high-level flow I’ll use:

Since you may have the code, be at liberty to regulate any a part of this to your:

- GPUs

- Deployment process

- Experimentation Framework

- Etc

You won’t hurt my feelings.

Load Testing Parameters

VUs and Batch Size are vital because these influence how well we reap the benefits of all of the compute available within the GPU. A big enough Batch Size makes sure we’re fully utilizing the Streaming Multiprocessors and VRAM. There are scenarios where we’ve VRAM left over but there’s a bandwidth cost that stops throughput from increasing. So experimentation will help us. VUs allow us to be certain that we’re fully utilizing the batch size we’ve available.

These are the predominant parameters I will be testing:

INFINITY_BATCH_SIZE- That is what number of documents will make a forward pass within the batch within the model

- Too low and we cannot be utilizing the GPU

- Too high and the GPU cannot handle the massive input

VUs- That is the variety of Virtual Users simulating parallel client requests that is distributed to K6

- It will possibly be hard to simulate numerous users, and every machine will vary.

- GPUs

- We have now a variety of GPUs available on Inference Endpoints

- I prioritized those with the perfect performance/cost ratio

- CPUs

- I omitted these since Nvidia-T4s are so low-cost that CPUs didn’t seem appealing upon light testing. I left some code to check this if a user is interested though!

Depending in your model you would possibly want to contemplate:

- Which Docker image you might be using. [

'michaelf34/infinity:0.0.75-trt-onnx','michaelf34/infinity:0.0.75']- There are quite a few Infinity Images that may support different backends. You need to consider which of them are most applicable to your hardware/model/configuration.

INFINITY_COMPILEwhether or not you would like to usetorch.compile()docsINFINITY_BETTERTRANSFORMERwhether or not you wish torch to make use of Higher Transformer

K6

K6 is great since it lets you pre-allocate VUs and stop some insidious bugs. It’s quite flexible in how you might be sending requests. I made a decision to make use of it in a particular way.

Once I’m calling a k6 experiment, I mainly need to know what the throughput and average latency is for the requests, and have just a few sanity checks for the load testing parameters I even have chosen. I also need to do a sweep which implies many experiments.

I exploit the shared-iterations executor (docs) which implies K6 shares iterations between the variety of VUs. The test ends once k6 executes all iterations. This permits me to have an affordable time-out, but in addition put through enough requests to have a good confidence that I can discriminate between load testing parameters decisions in my sweep. In contrast to other executors, this enables me to be confident that I’m simulating the client working as hard as possible per VU which should show me what the most affordable option is.

I exploit 10_000 requests† and have a max experiment time of 1 min. So if 10_000 requests aren’t finished by 1 minute, then that experiment is over.

export const options = {

scenarios: {

shared_load_test: {

executor: 'shared-iterations',

vus: {{ pre_allocated_vus }},

iterations: 10000,

maxDuration: '1m',

},

},

};

Stats

- P95†† and Average Latency

- Throughput

Sanity Checks

- Accuracy (Classification only)

- Test Duration

- Successful Requests

- Format validation

† I exploit less max requests for the Vision Embeddings provided that the throughput is far lower and pictures are heavy.

†† P95 signifies that 95% of requests complete inside this time. It represents the worst-case latency for many users.

Orchestration

You’ll find the three notebooks that put the optimization workflow together here:

The predominant purpose was to get my experiments defined, launch the right Inference Endpoint with the appropriate parameters, and launch k6 with the appropriate parameters to check the endpoint.

I made a pair design decisions which it’s possible you’ll need to think through to see in the event that they be just right for you:

- I do an exponential increase of VUs then a binary search to search out the perfect value

- I don’t treat the outcomes as exactly repeatable

- For those who run the identical test multiple times you’ll get barely different results

- I used an improvement threshold of two% to come to a decision if I should keep searching

Classification

Introduction

Text Classification can have a wide range of use-cases at scale, like Email Filtering, Toxicity Detection in pre-training datasets, etc. The OG classic architecture was BERT, and quickly many other architectures got here about. Do note that in contrast to popular decoder models, these must be fine-tuned in your task before using them. Today I believe the next architectures† are essentially the most notable:

- DistilBERT

- Good task performance, Great Engineering performance

- It made some architectural changes from OG Bert and is just not compatible for classification with TEI

- DeBERTa-v3

- Great task performance

- Very slow engineering performance†† as its unique attention mechanism is difficult to optimize

- ModernBERT

- Uses Sequence Packing and Flash-Attention-2

- Great task performance and great engineering performance††

† Do note that for these models, you typically must fine-tune this in your data to perform well

†† I’m using “Engineering performance” to indicate anticipated latency/throughput

Experiment

I selected DistilBERT to give attention to because it’s a terrific lightweight alternative for a lot of applications. I compared 2 GPUs, nvidia-t4 and nvidia-l4 in addition to 2 Infinity Docker Images.

Results

You possibly can see the ends in an interactive format here or within the space embedded below within the Evaluation section. That is the most affordable configuration across the experiments I ran:

| Category | Best Value |

|---|---|

| Cost of 1B Inputs | $253.82 |

| Hardware Type | nvidia-L4 ($0.8/hr) |

| Infinity Image | default |

batch_size |

64 |

vus |

448 |

Embedding

Introduction

Text Embeddings are a loose way of describing the duty of taking a text input and projecting it right into a semantic space where close points are similar in meaning and distant ones are dissimilar (example below). That is used heavily in RAG and is a very important a part of AI search (which some are fans of).

There are numerous architectures that are compatible, and you may see essentially the most performant ones within the MTEB Leaderboard.

Experiment

ModernBERT is essentially the most exciting encoder release since DeBERTa back in 2020. It has all of the ahem modern tricks built into an old and familiar architecture. It makes for a horny model to experiment with because it’s much less explored than other architectures and has loads more potential. There are quite a few improvements in speed and performance, but essentially the most notable for a user is probably going the 8k context window. Do take a look at this blog for a more thorough understanding.

It is important to notice that Flash Attention 2 will only work with more modern GPUs as a consequence of the compute capability requirement, so I opted to skip the T4 in favor of the L4. An H100 would also work very well here for the heavy hitters category.

Results

You possibly can see the ends in an interactive format here. That is the most affordable configuration across the experiments I ran:

| Category | Best Value |

|---|---|

| Cost of 1B Inputs | $409.44 |

| Hardware Type | nvidia-L4 ($0.8/hr) |

| Infinity Image | default |

batch_size |

32 |

vus |

256 |

Vision Embedding

Introduction

ColQwen2 is a Visual Retriever which is predicated on the Qwen2-VL-2B-Instruct and uses ColBERT style multi-vector representations of each text and pictures. We will see that it has a posh architecture in comparison with the encoders we explored above.

There are quite a few use-cases which could profit from this at large scale like, e-commerce search, multi-modal recommendations, enterprise multi-modal RAG, etc

ColBERT style is different than our previous embedding use-case because it breaks the input into multiple tokens and returns a vector for every as a substitute of 1 vector for the input. You’ll find a wonderful tutorial from Jina AI here.This could result in superior semantic encoding and higher retrieval, but can be slower, and dearer.

I’m excited for this experiment because it explores 2 lesser known concepts, vision embeddings and ColBERT style embeddings†. There are just a few things to notice about ColQwen2/VLMs:

- 2B is ~15x greater than the opposite models we checked out on this blog

- ColQwen2 has a posh architecture with multiple models including a decoder which is slower than an encoder

- Images can easily devour a variety of tokens

- API Costs:

- Sending images over an API is slower than sending text.

- You’ll further encounter larger egress costs in case you are on a cloud

†Do take a look at this more detailed blog if that is latest and interesting to you.

Experiment

I desired to try a small and modern GPU just like the nvidia-l4 because it should give you the chance to suit the 2B param model but in addition scale well because it’s low-cost. Like the opposite embedding model, I’m various batch_size and vus.

Results

You possibly can see the ends in an interactive format here. That is the most affordable configuration across the experiments I ran:

| Category | Best Value |

|---|---|

| Cost of 1B Inputs | $44,496.51 |

| Hardware Type | nvidia-l4 |

| Infinity Image | default |

batch_size |

4 |

vus |

4 |

Evaluation

Do take a look at the detailed evaluation on this space (derek-thomas/classification-analysis) for the classification use-case (hide side-bar and scroll down for the charts):

Conclusion

Scaling to 1B+ classifications or embeddings per day is a non-trivial challenge, but with the appropriate optimizations, it will possibly be made cost-effective. From my experiments, just a few key patterns emerged:

- Hardware Matters – NVIDIA L4 ($0.80/hr) consistently provided the perfect balance of performance and price, making it the popular alternative over T4 for contemporary workloads. CPUs weren’t competitive at scale.

- Batch Size is Critical – The sweet spot for batch size varies by task, but typically, maximizing batch size without hitting GPU memory and bandwidth limits is the important thing to efficiency. For classification, batch size 64 was optimal; for embeddings, it was 32.

- Parallelism is Key – Finding the appropriate variety of Virtual Users (VUs) ensures GPUs are fully utilized. An exponential increase + binary search approach helped converge on the perfect VU settings efficiently.

- ColBERT style Vision Embeddings are Expensive – At over $44,000 per 1B embeddings, image-based retrieval is 2 orders of magnitude costlier than text-based tasks.

Your data, hardware, models, etc might differ, but I hope you discover some use within the approach and code provided. The most effective technique to get an estimate is to run this on your individual task along with your own configurations. Let’s get exploring!

Special because of andrewrreed/auto-bench for some inspiration, Michael Feil for creating Infinity. Also because of Pedro Cuenca, Erik Kaunismaki, and Tom Aarsen for helping me review.

References

Appendix

Sanity Checks

It is important to scale sanity checks as your complexity scales. Since we’re using subprocess and jinja to then call k6 I felt removed from the actual testing so I put just a few checks in place.

Task Performance

The goal of task performance is that for a particular configuration we’re performing similarly to what we expect. Task Performance can have different meanings across tasks. For classification I selected accuracy, and for embeddings I skipped it. We could have a look at average similarity and other similar metrics. It gets a bit more complex with ColBERT style since we’re getting many vectors per request.

Although 58% is not bad for some 3 class classification tasks, it’s irrelevant. The goal is to be certain that that we’re getting the expected task performance. If we see a major change (increase or decrease) we ought to be suspicious and take a look at to know why.

Below is a terrific example from the classification use-case since we are able to see an especially tight distribution and one outlier. Upon further investigation the outlier is as a consequence of a low amount of requests sent.

You possibly can see the interactive results visualized by nbviewer here:

Failed Requests Check

We must always expect to see no failed requests as Inference Endpoints has a queue to handle extra requests. That is relevant for all 3 use-cases: Classification, Embedding, and Vision Embedding.

sum(df.total_requests - df.successful_requests) allows us to see if we had any failed requests.

Monotonic Series – Did we try enough VUs?

As described above we’re using a pleasant strategy of using exponential increases after which a binary search to search out the perfect variety of VUs. But how can we know that we tried enough VUs? What if we tried the next amount of VUs and throughput kept increasing? If that is the case then we’d see a monotonically increasing relationship between VUs and Throughput and we might must run more tests.

You possibly can see the interactive results visualized by nbviewer here:

Embedding Size Check

Once we request an embedding it is smart that we’d all the time get back an embedding of the identical size as specified by the model type. You possibly can see the checks here:

ColBERT Embedding Count

We’re using a ColBERT style model for Vision Embedding which implies we ought to be getting multiple vectors per image. It’s interesting to see the distribution of those because it allows us to ascertain for anything unexpected and to get to know our data. To accomplish that I stored the min_num_vectors, avg_num_vectors, max_num_vectors, within the experiments.

We must always expect to see some variance in all 3, but it surely’s okay that min_num_vectors and max_num_vectors have the identical value across experiments.

You possibly can see the check here:

Cost Evaluation

Here’s a short description, but you may get a more detailed interactive experience within the space: derek-thomas/classification-analysis

Best Image by Cost Savings

For the classification use-case we checked out 2 different Infinity Images, default and trt-onnx. Which one was higher? It is best if we are able to compare these across the identical settings (GPU, batch_size, VUs). We will simply group our results by those settings after which see which one was cheaper.

Cost vs Latency

This can be a key chart as for a lot of use-cases there’s a maximum latency that a user can experience. Normally if we allow the latency to extend we are able to increase throughput making a trade-off scenario. That is true in all of the use-cases I’ve checked out here. Having a pareto curve is great to assist visualize where that tradeoff is.

Cost vs VUs and Batch Size Contour Plots

Lastly it is important to construct intuition on what is going on once we try these different settings. Can we get beautiful idealized charts? Can we see unexpected gradients? Do we want more exploration in a region? Could we’ve issues in our setup like not having an isolated environment? All of those are good questions and a few might be tricky to reply.

The contour plot is built by interpolating intermediate points in an area defined by the three dimensions. There are a pair phenomena which are value understanding:

- Color Gradient: Shows the associated fee levels, with darker colours representing higher costs and lighter colours representing lower costs.

- Contour Lines: Represent cost levels, helping discover cost-effective regions.

- Tight clusters: (of contour lines) indicate costs changing rapidly with small adjustments to batch size or VUs.

We will see a posh contour chart with some interesting results from the classification use-case:

But here’s a much cleaner one from the vision-embedding task:

Infinity Client

For actual usage, do think about using the infinity client. Once we are benchmarking it’s good practice to make use of k6 to know what’s possible. For actual usage, use the official lib, or something close for just a few advantages:

- Base64 means smaller payloads (faster and cheaper)

- The maintained library should make development cleaner and easier

- You’ve inherent compatibility which is able to make development faster

You furthermore mght have OpenAI lib compatibility with the Infinity backend as another choice.

For example vision-embeddings might be accessed like this:

pip install infinity_client && python -c "from infinity_client.vision_client import InfinityVisionAPI"

Other Lessons Learned

- I attempted deploying multiple models on the identical GPU but didn’t see major improvements despite having leftover VRAM and GPU processing power left, this is probably going as a consequence of the bandwidth cost of processing a big batch

- Getting K6 to work with images was a headache until I learned about SharedArrays

- Image Data might be super cumbersome to work with

- The important thing to debugging K6 when you find yourself generating scripts is to manually run K6 and have a look at the output.

Future Improvements

- Have the tests run in parallel while managing a world max of

VUswould save a variety of time - Have a look at more diverse datasets and see how that impacts the numbers