Handling load from multiple users in parallel is crucial for the performance of LLM applications. Within the previous part of our series on LLM performance, we discussed queueing strategies for the prioritization of various users. On this second part, we are going to now concentrate on the concurrent processing of requests, and the way it impacts relevant metrics comparable to latency and throughput in addition to GPU resource utilization.

At TNG, we’re self-hosting quite a few Large Language Models on our cluster of 24 H100 GPUs. It supports 50 different applications, handles over 5,000 inferences per hour, and generates greater than ten million tokens each day.

The Two Stages of Token Generation: Prefill and Decode

Most LLMs generate text token by token, which guarantees that each recent token is computed based on all preceding tokens (this model property is named auto-regressive). The primary output token relies on all prompt tokens, however the second output token already relies on all prompt tokens plus the primary output token, and so forth. As a consequence, token generation can’t be parallelized at the extent of a person request.

In LLMs with attention mechanisms, computing a brand new token requires calculating key, value, and query vectors for every preceding token. Fortunately, the outcomes of some particular calculations will be re-used for subsequent tokens. This idea is generally known as key-value (KV) cache. For each additional output token, only another set of key and value vectors must be calculated and added to the KV cache. For the very first output token, nevertheless, we start with an initially empty KV cache and want to calculate as many sets of key and value vectors as there are tokens within the input prompt. Luckily, and in contrast to any later token generation, all input tokens are known from the start, and we will parallelize the calculation of their respective key and value vectors. This difference motivates the excellence between the prefill (computing the primary output token) and the decode phase (computing any later output token).

Within the prefill phase, the calculations for all input tokens will be executed in parallel, while within the decode phase, no parallelization is feasible on the extent of individual requests.

Metrics

The difference between the prefill and decode phases can be reflected in two key metrics for text generation: Time to first token and time per output token. The time to first token is given by the latency of the prefill phase, while the time per output token is the latency of a single decode step. Despite the fact that the prefill phase also generates only a single token, it takes for much longer than a single decode step, because all input tokens must be processed. Alternatively, the prefill phase is far faster with respect to the variety of input tokens than a decode phase for a similar variety of output tokens (this difference is the explanation why industrial LLM APIs charge input tokens at a much lower rate than ouput tokens).

Each latencies are relevant metrics for interactive applications like a chat bot. If users should wait for greater than 5 seconds before they see a response, they could think that the appliance is broken and leave. Similarly, if the text generation is as slow as 1 token per second, they’d not be patient enough to attend until it’s finished. Typical latency targets for interactive applications are 100-300ms per output token (i.e. a token generation speed of 3-10 tokens per second, no less than as fast as reading speed, which ideally allows for skimming the output text because it is being generated), and a time to first token of three seconds or less. Each of those latency targets will be quite difficult to attain, depending on the model size, hardware, prompt length, and concurrent load.

Other, non-interactive use cases may not be all in favour of the latencies of individual requests, but only in the whole token throughput (tokens per second, summed up over all concurrent requests). This could possibly be relevant when you would like to generate translations for books, or summarize code files in a big repository.

As we are going to see in a later section, there generally is a trade-off between maximizing the whole throughput and minimizing latencies for every individual request.

Resource Utilization

Due to parallelized calculation for all input tokens, the prefill phase may be very GPU compute-intensive. In contrast, the decode step for a person output token utilizes little or no computational power; here, the speed is often limited by the GPU memory bandwidth, i.e. how quickly model weights and activations (including key and value vectors) will be loaded from and accessed inside the GPU memory.

Typically, token throughput will be increased until the GPU utilization (w.r.t. computational power) is saturated. Within the prefill phase, a single request with a protracted prompt can already achieve maximum GPU utilization. Within the decode phase, the GPU utilization will be increased by batch processing of multiple requests. As a consequence, once you plot the token throughput as a function of the variety of concurrent requests, you see an almost linear increase in throughput at low concurrency, because this memory-bound regime advantages from larger batch sizes. Once the GPU utilization saturates and the compute-bound regime is entered, the throughput stays invariant to a rise in concurrency.

Concurrent Processing

We are going to now consider how exactly an inference engine handles multiple requests that arrive inside a short while interval.

Each the prefill and decode phases could make use of batching strategies to use the identical set of operations to different requests. But what are the results of running prefill and decode of various requests at the identical time?

Static Batching vs. Continuous Batching

Probably the most naive type of batching is named static batching. (1) You begin with an empty batch, (2) you fill the batch with as many items as are waiting and as fit into the batch, (3) you process the batch until all batched items are finished, and (4) you repeat the procedure with a brand new empty batch.

All requests start their prefill phase at the identical time. Since prefill is only a single, but heavily parallelized, GPU operation (consider it as a really large matrix multiplication), the prefill phases of all concurrent requests are accomplished at the identical time. Then, all decode phases start concurrently. Requests with fewer output tokens would finish earlier, but due to static batching the subsequent waiting request can only start once the longest batched request has been accomplished.

Static batching optimizes the time per output token, because the decode phase is uninterrupted. The downside is a really inefficient resource utilization. Since a single, long prompt can already saturate the compute power during prefill, handling multiple prefills in parallel doesn’t yield a speed-up and will definitely max out GPU utilization. In contrast, the GPU will likely be underutilized throughout the decode phase, since even a lot of concurrent decodes just isn’t as compute-intensive because the prefill for a protracted prompt.

The largest drawback, nevertheless, is the doubtless long time to first token. Even when some short requests finish early, the subsequent queuing request has to attend for the longest decode within the batch to complete before its prefill can begin. For this reason flaw of static batching, inference engines typically implement continuous batching strategies. Here, any accomplished request is straight away faraway from the batch, and the batch space is full of the subsequent request in line. As a consequence, every continuous batching strategy has to cope with concurrency between prefill and decode phases.

Prefill-First

In an attempt to scale back the waiting time of requests, inference engines comparable to vLLM and TGI schedule the prefill phase of recent requests as soon as they arrive and fit into the present batch. It is feasible to run the prefill of recent requests in parallel with a single decode step for every of all previous requests, but since every thing is executed in the identical GPU operation, its duration is dominated by the prefill, and for each request within the decode phase only a single output token will be generated in that point. Due to this fact, this prioritization of prefills minimizes the time to first token but interrupts the decode phase of already running requests. In a chat application, users can experience this as pausing of the streamed token generation when other users submit long prompts.

In the next measurement you possibly can see the effect of continuous batching with a prefill-first strategy.

Chunked Prefill

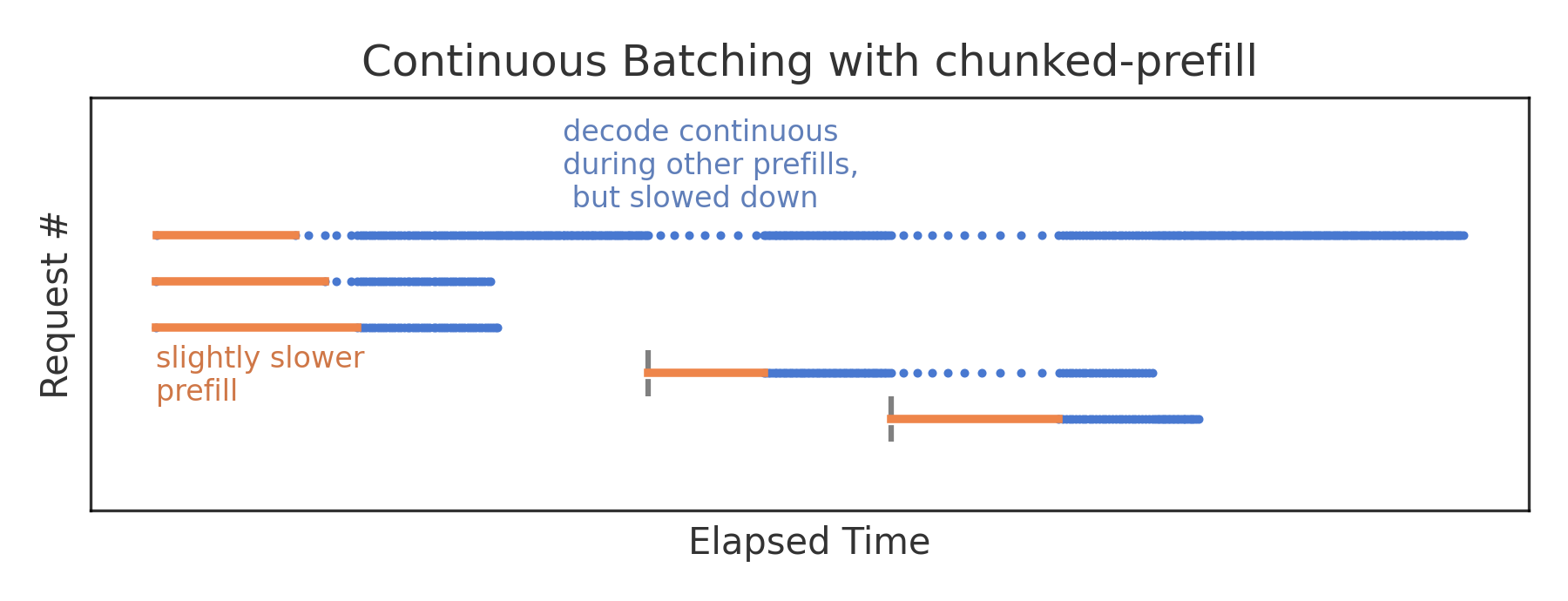

One approach to alleviate the impact of interruptive prefills on running decodes is a chunked prefill. As an alternative of processing the complete prompt in a single prefill step, it might be distributed over multiple chunks. Then there will be as many concurrent decode steps during prefill as there are prefill chunks (versus only a single decode step per concurrent request during the complete prefill). A chunked prefill step will still take longer than an isolated decode step, but for small chunk sizes the user now experiences only a slowing-down of token generation as a substitute of a whole pause; this reduces the typical time per output token. From the attitude of the interrupting request, a chunked prefill comes with some overhead and takes a bit longer than an isolated, contiguous prefill, so there’s a small increase within the time to first token. With the chunk size we now have a tuning knob for prioritizing either the time to first token or the time per output token. Typical chunk sizes are between 512 and 8192 tokens (the vLLM default was 512 when chunked prefill was first implemented, and was later updated to higher values).

The largest advantage of this strategy is, nevertheless, that chunked prefill maximizes resource efficiency. Prefill is compute-intensive, while decode is memory-bound. By running each operations in parallel, one can increase the general throughput without being limited by GPU resources. In fact, maximum efficiency is barely achieved at a certain chunk size, which in turn relies on the precise load pattern.

In a regular vLLM deployment and for evenly sized requests, we observed that chunked prefill increased the whole token throughput by +50%. It’s now enabled for each vLLM deployment of self-hosted LLMs at TNG. Overall, chunked prefill is a great default strategy for many use cases. Optimizing the chunk size, nevertheless, is sort of difficult in environments with unpredictable load patterns (like TNG with its many diverse applications); typically, you persist with the defaults.

Whatever the exact chunk size configuration, concurrent processing with chunked prefill comes with two challenges that we are going to address in the subsequent article.